PALESTINE -- PEACE NOT APARTHEID |

|

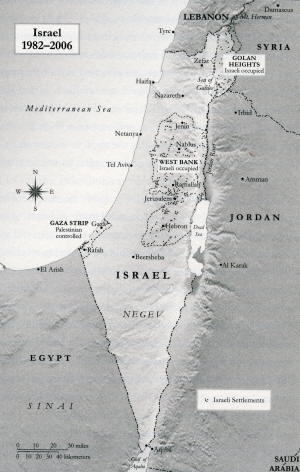

Chapter 4: THE KEY PLAYERS THE PALESTINIANS To understand present circumstances in the Middle East, it is necessary to take a closer look at the Palestinians and the Israelis. We can begin with a brief general description of the Palestinians, whose future status must be a focal point for progress toward peace. What is Palestine, and who are the Palestinians? The borders of this contentious area, also called the Land of Canaan or the Holy Land, have never been conclusively defined. The name is an ancient one, derived from the Philistines, who lived along the Mediterranean seacoast and were also known as People of the Sea. The Bible does not portray these people very attractively, because they did not worship God and they competed with the authors and heroes of the scriptures for control over parts of Canaan. Formidable warriors and some of the earliest users of iron weaponry, they were usually able to prevail over their enemies -- even the powerful King David. Roman conquerors, after smashing the Second Jewish Revolt in A.D. 135, set out to obliterate the historic Jewish presence in the land. They changed the name of Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina, and Judaea became the province of Syria Palaestina, later simply Palaestina. When Christianity became the religion of the Roman Empire, the name of Jerusalem was revived. The name Palaestina, translated into Arabic as Filistin, survived the seventh-century Arab conquest, and the name prevailed even as the borders of the region have fluctuated through the centuries. A succession of Turks, Kurds, and European Crusaders ruled Palestine until the Ottoman Turks incorporated Palestine into their empire in 1516. They were on the losing side in World War I, and France and Great Britain initially assumed authority over the various parts of the Middle East. The League of Nations assigned to Great Britain the supervision of the Mandate of Palestine, which we now know as the lands of Israel, the West Bank, Gaza, and Jordan. After Jordan was separated from the Mandate in 1922 , the remaining territory between the Jordan River and the Mediteranean Sea became known as Palestine. Although Christian and Muslim Arabs had continued to live in this same land since Roman times, they had no real commitment to establish a separate and independent nation. Their concern was with family and tribe and, for the Muslims, the broader world of Islam. Strong ideas of nationhood began to take shape among the Arabs only when they saw increasing numbers of Zionists immigrate to Palestine, buying tracts of land for permanent homes with the goal of establishing their own nation. In 1947 the United Nations approved a partition plan for Palestine. A Jewish state was to include 55 percent of this territory (Map 2), Jerusalem and Bethlehem were to be internationalized as holy sites, and the remainder of the and was to constitute an Arab state. The Jewish Agency (an official group that represented the Jewish community in Palestine to the British Mandate) and other Zionist representatives approved the plan, but Arab leaders were almost unanimous in their opposition. When Jews declared their independence as a nation, the Arabs attacked militarily but were defeated. The 1949 armistice demarcation lines became the borders of the new nation of Israel and were accepted by Israel and the United States, and recognized officially by the United Nations. Israelis had taken 77 percent of the disputed land, and the Palestinians were left with two small separate areas, to be known as the West Bank (annexed by Jordan) and Gaza (administered by Egypt). Jews who lived within their new nation took the name Israelis, while Christian and Muslim Arabs in the Holy Land outside of Israel preferred to be known as Palestinians. The Palestinians' own most expansive definition includes "all those, and their descendants, who were residents of the land before 14 May 1948 [when Israel became a state]." When Britain conducted a census in Palestine in 1922, there were about 84,000 Jews and 670,000 Arabs, of whom 71,000 were Christians. By the time the area was partitioned by the United Nations, these numbers had grown to about 600,000 Jews and 1.3 million Arabs, 10 percent of whom were Christians. During and after the 1948 war, about 420 Palestinian villages in the territory that became the State of Israel were destroyed and some 700,000 Palestinian residents fled or were driven out. The Palestinians and individual Arab leaders continued their vehement objections to the increasing Israeli encroachment on what they considered to be their lands and rights. However, it was not until the announcement of Israel's plans to divert water from the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River to irrigate western Israel and the Negev desert that the first summit meeting of Arab leaders took place early in 1964 and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was formally organized. The United Nations estimated that by this time there were 1.3 million Palestinian refugees, with one-fourth in Jordan, about 150,000 each in Lebanon and Syria, and most of the others in West Bank and Gaza refugee camps. In May 1967, after military clashes between Syria and Israel, Egypt blockaded the Straits of Tiran and ordered the removal of U.N. Emergency Forces stationed along the Israel-Egypt border. Other Arab states put their troops on alert. On June 5, Israel launched preemptive strikes, moving first against Egypt and Syria, then against Jordan. Within six days Israeli military forces had occupied the Golan Heights, Gaza, the Sinai, Jerusalem, and the West Bank. As a result of that conflict, 320,000 more Arabs were forced to leave the additional areas in Syria, Egypt, Jordan, and Palestine that were occupied by Israel. A number of U.N. resolutions were adopted (with U.S. support and Israeli approval), reemphasizing the inadmissibility of acquisition of land by force, calling for Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories, and urging that the more needy and deserving refugees be repatriated to their former homes. [1] After the 1967 war, most Arab leaders acknowledged the preeminence of the PLO as representing the Palestinians, and a quasi government was formed to deal with matters such as welfare, education, information, health, and security. In 1969 the PLO found a strong leader in Yasir Arafat, a well-educated Palestinian who was the head of al-Fatah, a guerrilla organization. As chairman, Arafat turned much of his attention to raising funds for the care and support of the refugees and inspiring worldwide contributions to their cause. At the same time, the PLO was able to establish diplomatic missions in more than a hundred countries and used its observer status in the United Nations to become one of the most powerful voices in international councils. But persistent PLO attacks on Israelis continued, both within the occupied territories and from the adjacent Arab nations. The next exodus of Palestinians was from Jordan in 1970, the result of a civil war between a powerful force of PLO militants who had settled in Jordan and King Hussein's regular forces. When the king's troops prevailed, a new flood of refugees moved from Jordan to Lebanon, where the Palestinians had a host country that was not strong enough to reject them and where the PLO was able to form a governmental organization and even an independent militia. In much of Lebanon, as had been the case in Jordan, the PLO was soon powerful enough to challenge the sovereignty of the host government itself, and its forces launched frequent attacks across the border against Israel. These guerrilla raids brought swift Israeli retaliation, much of which fell on Lebanese civilians, who increasingly resented their troublesome guests. The country became embroiled in civil conflict, and Syrian forces moved in to restore order in June 1976 (the year I was elected president), working out an agreement to limit the PLO militia to prescribed locations and to restrict guerrilla attacks from Southern Lebanon into Israel. Map 5: Israel 1982-2006 * * * I have found Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza to be focused on their personal problems under Israeli occupation, but there are a variety of concerns among Palestinian leaders in other countries. Their attitudes and commitments have been shaped by earlier events affecting their own lives, and nowadays few have any direct contact with either the Jews or Arabs who still live in Palestine. They were driven in 1948 and 1967 from what they still consider their homes, and many I have met have claimed the right to use any means at their disposal, including armed struggle, to regain their lost rights. When I met with Yasir Arafat in 1990, he stated, "The PLO has never advocated the annihilation of Israel. The Zionists started the 'drive the Jews into the sea' slogan and attributed it to the PLO. In 1969 we said we wanted to establish a democratic state where Jews, Christians, and Muslims can all live together. The Zionists said they do not choose to live with any people other than Jews. ... We said to the Zionist Jews, all right, if you do not want a secular, democratic state for all of us, then we will take another route. In 1974 I said we are ready to establish our independent state in any part from which Israel will withdraw. As with Israelis, there are many differences among the voices coming from the PLO, and listeners interpret the words to suit their own ends." When I asked Arafat about the purposes of the PLO, he seemed somewhat taken aback that I needed to ask such a question. He gave me a pamphlet that stated, "The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) is the national liberation movement of the Palestinian people. It is the institutional expression of Palestinian nationhood. ... The PLO is to the Palestinian people what other national liberation movements have been to other nations. It is their means to reassert and reaffirm a denied national identity, to recover a suppressed history, to safeguard a popular heritage, to rebuild demolished institutions, to maintain national unity threatened by physical dispersion, and to struggle for usurped homeland and denied national rights. In brief, the PLO is the Palestinian people's quest to resurrect their national existence." It is interesting how many times "national" appears in this short statement. The PLO is a loosely associated umbrella organization bound together by common purpose, but it comprises many groups eager to use diverse means to reach their goals. The PLO has been recognized officially by all Arab governments as the "sole and legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, both at home [in Palestine] and in the Diaspora [in other nations]." It plays a strong role in the United Nations, and the many U.N. resolutions supporting Palestinians are considered to be proof of their effectiveness and the rightness of their cause. [2] The political prestige and influence of the Palestinians seem to increase in inverse proportion to their military defeats. After losing its effort to use Jordan as a base of operations against Israel in 1970-71, the PLO rebounded as the exclusive leader of the Palestinian people, with a strong base of operations in Lebanon. After Camp David and the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty removed Egypt as a major supporter, the PLO seemed to gain new life as other irate Arabs renewed their commitment to the cause. THE ISRAELIS One must consider the Jewish experience of the past. Jews suffered for centuries the pain of the Diaspora and persistent persecution in almost every nation in which they dwelt. Despite their remarkable contributions in all aspects of society, many Jews were killed and others driven from place to place by Christian rulers. Although not given the same rights as Muslims, both Christians and Jews who lived in Islamic countries often fared better than non-Christians in Christendom, because the Prophet Muhammad commanded his followers to recognize the common origins of their faith through Abraham, to honor their prophets, and to protect their believers. Muslim leaders favored the Jews over Christians because they saw them as less competitive in expanding their political and religious influence. President Anwar Sadat made these points often while he was negotiating with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and me at Camp David. Nationalism became a powerful force in nineteenth-century Europe, and it influenced Jews living there to create the Zionist movement. In Western Europe, the unique identity of the Jewish population was threatened by assimilation into Christian and secular society. But almost three-fourths of Jews were living in Eastern Europe, where persecution continued, and it was there that the seeds of Zionism were nourished. Although a majority of Jewish emigrants went to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, increasing demands were heard for the establishment of a Jewish state -- both to escape oppression and to fulfill an interpretation of biblical prophecies. Although exact data are not available, it is estimated that in 1880 there were only 30,000 Jews in Palestine, scattered among 600,000 Muslim and Christian Arabs. By 1930 their numbers had grown to more than 150,000. The Arabs in Palestine fought politically and militarily against these new settlers, but they could agree on little else and dissipated their strength and influence by contention among themselves. The British, who succeeded the ottoman Turks after World War I as rulers of Palestine, attempted to contain the bloody disputes by restricting immigration of Jews to the Holy Land, despite desperate appeals from those who faced increasing threats and racial abuse. And then came the world's awareness of the horrors of the Holocaust, and the need to acknowledge the Zionist movement and an Israeli state. There had been further waves of Jewish and Gentile immigration into Palestine, as indicated by official British data: the Arab population increased from 760,000 in 1931 to 1,237,000 in 1945, mostly attracted by economic opportunity, while the number of Jews during the same period increased to 608,000, primarily because of persecution in Europe. British forces withdrew in May 1948 and Israel declared itself an independent state, recognized almost immediately by President Harry Truman on behalf of the United States. At that point Arab troops from Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Transjordan, and Iraq joined Palestinians in attacking Israel, but their separate national forces were not well coordinated and there was some doubt about their specific objectives. The Israelis, in contrast, were cohesive, better armed, well led, and highly motivated as they fought for their lives and their new nation. The war ended in 1949 with armistice agreements signed between Israel and the proximate countries, based on Israel's acceptance of a divided Palestine (77 percent Israeli, 23 percent Arab) and the assumption that Jordan would control what is now known as East Jerusalem and the West Bank. No serious consideration was given by Arab leaders or the international community to establishing a separate Palestinian state while these people's ancient homeland was divided among Jordan, Israel, and Egypt. The continuing state of war between Israel and its neighbors caused many Jews to flee Syria, Iraq, and other Arab countries to Israel, while Palestinian refugees were scattered more broadly. From all sides, the Palestinians and sometimes troops of their host countries launched spasmodic but persistent attacks against the Israelis, who responded with retaliatory raids. The major defining war was the one in 1967. Israel prevailed after only six days of fighting and occupied lands of Egypt and Syria and the parts of Palestine controlled by Jordan. Of necessity, Israel has maintained one of the most powerful military forces in the world and has managed to dominate its adversaries, but none of the several wars has resolved any of the basic causes of conflict. According to official Israeli figures, about 22,000 Israelis have died in military confrontations since the nation was founded. During most engagements, the number of Arab casualties has been three or four times greater than Israeli casualties. In addition, large numbers of Christian and Muslim Arabs have either been driven into exile or put under military rule each time Israel has occupied and retained more Arab territory. This has intensified the fear, hatred, and alienation on both sides, and made more difficult the ultimate reconciliation that must come before peace, justice, and security can prevail in the region. When I travel in the Middle East, one persistent impression is the difference in public involvement in shaping national policy. It is almost fruitless to seek free expressions of opinion from private citizens in Arab countries with more authoritarian leadership, even among business leaders, journalists, and scholars in the universities. Only among Israelis, in a democracy with almost unrestricted freedom of speech, can one hear a wide range of opinion concerning the disputes among themselves and with Palestinians, other Arabs, and often with former presidents and other distinguished guests. When I made a presidential visit to Israel in March 1979, I was invited to address the Knesset. I was shocked by the degree of freedom permitted the members of the parliament in their exchanges. Although I was able to conclude my remarks with just a few interruptions, it was almost impossible for either Prime Minister Begin or others to speak. Instead of being embarrassed by the constant interruptions and even the physical removal of an especially offensive member from the chamber, Begin seemed to relish the verbal combat and expressed pride in the unrestrained arguments. During an especially vituperative exchange, he leaned over to me and said proudly, "This is democracy in action." With the exception of sometimes excessive military censorship, this freedom of expression prevails in the news media, and in private discussions in Israel there is a noticeable desire to explore every facet of domestic and international political life. Only among some of the Israeli Arabs is there an obvious reluctance to speak freely. Although important disagreements exist among opposing political leaders in the Israeli debates, the differences pale when questions of Israel's security are concerned. Then the population closes ranks. A common religion, a shared history, and memories of horrible suffering bind them together in a strength and cohesion unequaled in the Middle East or perhaps anywhere in the world. The key to the future of Israel will not be found outside the country but within. It is not likely that any combination of Arab powers or even the powerful influence of the United States could force decisions on Israel concerning East Jerusalem, the West Bank, Palestinian rights, or the occupied territories of Syria. These judgments will be made in Jerusalem, through democratic processes involving all Israelis who can express their views and elect their leaders. The crucial issues are being debated much more vehemently there than anywhere in the outside world, and a final decision has not been made. The outcome of this debate will shape the future of Israel; it may also determine the prospects for peace in the Middle East -- and perhaps the world. _______________ Notes: 1. Currently, it is estimated that there are about 9.4 million Palestinians, of whom 3.7 million live in the West Bank and Gaza, 200,000 in East Jerusalem, 1 million in Israel, and 4.5 million in other nations. 2. The Palestine Liberation Organization is the official organization that is recognized by the international community and has observer status in the United Nations. The Palestinian National Authority was formed in 1996, with leaders ejected within the occupied territories, where its jurisdiction exists.

|