|

AMERICA'S SECRET ESTABLISHMENT -- AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ORDER OF SKULL AND BONES |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

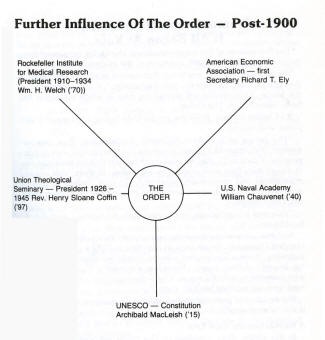

How the Order CONTROLS EDUCATION THE ORDER Memorandum Number One: It All Began At Yale The first volume of this series introduced The Order, presented three preliminary hypotheses with examples of the evidence to come. We also asserted that any group that wanted to control the future of American society had first to control education, i.e., the population of the future. This volume will outline the way in which education has been controlled by The Order. It all began at Yale. Even the official Yale history is aware of Yale's power and success: "The power of the place remain(s) unmistakable. Yale was organized. Yale inspired a loyalty in its sons that was conspicuous and impressive. Yale men in after life made such records that the suspicion was that even there they were working for each other. In short, Yale was exasperatingly and mysteriously successful. To rival institutions and to academic reformers there was something irritating and disquieting about old Yale College." [1] "Yale was exasperatingly and mysteriously successful," says the official history. And this success was more than obvious to Yale's chief competitor, Harvard University. So obvious, in fact, that in 1892 a young Harvard instructor, George Santanyana, went to Yale to investigate this "disturbing legend" of Yale power. Santanyana quoted a Harvard alumnus who intended to send his son to Yale -- because in real life "all the Harvard men are working for Yale men." [2] But no one has previously asked an obvious question -- Why? What is this "Yale power"? A Revolutionary Yale Trio In the 1850s, three members of The Order left Yale and working together, at times with other members along the way, made a revolution that changed the face, direction and purpose of American education. It was a rapid, quiet revolution, and eminently successful. The American people even today, in 1983, are not aware of a coup d'etat. The revolutionary trio were:

This notable trio were all initiated into The Order within a few years of each other (1849, 1852, 1853). They immediately set off for Europe. All three went to study philosophy at the University of Berlin, where post-Hegelian philosophy had a monopoly.

Notably also at the University of Berlin in 1856 (at the Institute of Physiology) was none other than Wilhelm Wundt, the founder of experimental psychology in Germany and the later source of the dozens of American PhDs who came back from Leipzig, Germany to start the modern American education movement. Why is the German experience so important? Because these were the formative years, the immediate post graduate years for these three men, the years when they were planning the future, and at this period Germany was dominated by the Hegelian philosophical ferment. There were two groups of these Hegelians. The right Hegelians, were the roots of Prussian militarism and the spring for the unification of Germany and the rise of Hitler. Key names among right Hegelians were Karl Ritter (at the University of Berlin where our trio studied), Baron von Bismarck, and Baron von Stockmar, confidential adviser to Queen Victoria over in England. Somewhat before this, Karl Theodor Dalberg (1744-1817), arch-chancellor in the German Reich, related to Lord Acton in England and an Illuminati (Baco v Verulam in the Illuminati code), was a right Hegelian. There were also Left Hegelians, the promoters of scientific socialism. Most famous of these, of course, are Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Heinrich Heine, Max Stirner and Moses Hess. The point to hold in mind is that both groups use Hegelian theory of the State as a start point, i.e., the State is superior to the individual. Prussian militarism, Nazism and Marxism have the same philosophic roots. And it left its mark on our trio. Daniel Coit Gilman Gilman wrote his sister in 1854 that what he most desired to do on returning home to America was to "influence New England minds." An extract from one Gilman letter is worth quoting at length. Daniel C. Gilman in 1852 as a senior in Yale College. Daniel C. Gilman in the early seventies as president of the University of California Gilman wrote his sister from St. Petersburg in April, 1854: And what do you think I am "keeping" for? Tell me, some day when you write, for every year makes me feel that I must draw nearer to a point. When I go home to America I must have some definite notions. Day and night I think of that time, and in all I see and do I am planning for being useful at home. I find my wishes cling more and more towards a home in New England, and I long for an opportunity to influence New England minds. If I am an editor, New York is the place; but, to tell the truth, I am a little afraid of its excitements, its politics, its money-making whirl. I look therefore more and more to the ministry as probably the place where I can do more good than anywhere else; that is to say, if I can have a congregation which will let me preach such things as we have talked over so many times in our up-stairs confabs. I am glad you remember those talks with pleasure, for I look upon them as among the greatest "providences" of my life. If ever I make anything in this world or another I shall owe it to the blessed influences of home. For me, it seems as though new notions and wider views of men and things were crowding upon me with wonderful rapidity, and every day and almost every hour I think of some new things which I wish to have accomplished in America.... I find my thoughts, unconsciously, almost, dwelling on the applications of Christianity or the principles of the New Testament to business, study, public education, political questions, travel, and so forth. I had a long talk with Mr. Porter in Berlin (it was three days long with occasional interruptions) on topics related to such as I have named, and he assures me that there are many places in New England ripe for the advocacy of some such views upon these questions as I have often hinted to you at home. I told him a great deal about my thoughts on such things, talking quite as freely and perhaps more fully than I have ever done with you girls at home: He seemed exceedingly interested .... He told me that the kind of preaching I spoke of was the kind now needed -- the kind which would be most influential of good -- and on the whole he encouraged me to attempt it. I feel more and more desirous to do so, and shall keep on, in all I see and hear abroad, with the examination of every influence now working upon men -- churches and schools, politics and literature ... [3] Daniel Coit Gilman is the key activist in the revolution of education by The Order. The Gilman family came to the United States from Norfolk, England in 1638. On his mother's side, the Coit family came from Wales to Salem, Massachusetts before 1638. Gilman was born in Norwich, Connecticut July 8, 1831, from a family laced with members of The Order and links to Yale College (as it was known at that time). Uncle Henry Coit Kingsley (The Order '34) was Treasurer of Yale from 1862 to 1886. James I. Kingsley was Gilman's uncle and a Professor at Yale. William M. Kingsley, a cousin, was editor of the influential journal New Englander. On the Coit side of the family, Joshua Coit was a member of The Order in 1853 as well as William Coit in 1887. Gilman's brother-in-law, the Reverend Joseph Parrish Thompson ('38) was in The Order. Gilman returned from Europe in late 1855 and spent the next 14 years in New Haven, Connecticut -- almost entirely in and around Yale, consolidating the power of The Order. His first task in 1856 was to incorporate Skull & Bones as a legal entity under the name of The Russell Trust. Gilman became Treasurer and William H. Russell, the cofounder, was President. It is notable that there is no mention of The Order, Skull & Bones, The Russell Trust, or any secret society activity in Gilman's biography, nor in open records. The Order, so far as its members are concerned, is designed to be secret, and apart from one or two inconsequential slips, meaningless unless one has the whole picture. The Order has been remarkably adept at keeping its secret. In other words, The Order fulfills our first requirement for a conspiracy -- i.e., IT IS SECRET. The information on The Order that we are using surfaced by accident. In a way similar to the surfacing of the Illuminati papers in 1783, when a messenger carrying Illuminati papers was killed and the Bavarian police found the documents. All that exists publicly for The Order is the charter of the Russell Trust, and that tells you nothing. On the public record then, Gilman became assistant Librarian at Yale in the fall of 1856 and "in October he was chosen to fill a vacancy on the New Haven Board of Education." In 1858 he was appointed Librarian at Yale. Then he moved to bigger tasks. The Sheffield Scientific School The Sheffield Scientific School, the science departments at Yale, exemplifies the way in which The Order came to control Yale and then the United States. In the early 1850s, Yale science was insignificant, just two or three very small departments. In 1861 these were concentrated into the Sheffield Scientific School with private funds from Joseph E. Sheffield. Gilman went to work to raise more funds for expansion. Gilman's brother had married the daughter of Chemistry Professor Benjamin Silliman (The Order, 1837). This brought Gilman into contact with Professor Dana, also a member of the Silliman family, and this group decided that Gilman should write a report on reorganization of Sheffield. This was done and entitled "Proposed Plan for the Complete Reorganization of the School of Science Connected with Yale College." While this plan was worked out, friends and members of The Order made moves in Washington, D.C., and the Connecticut State Legislature to get state funding for the Sheffield Scientific School. The Morrill Land Bill was introduced into Congress in 1857, passed in 1859, but vetoed by President Buchanan. It was later signed by President Lincoln. This bill, now known as the Land Grant College Act, donated public lands for State colleges of agriculture and sciences .... and of course Gilman's report on just such a college was ready. The legal procedure was for the Federal government to issue land scrip in proportion to a state's representation, but state legislatures first had to pass legislation accepting the scrip. Not only was Daniel Gilman first on the scene to get Federal land scrip, he was first among all the states and grabbed all of Connecticut's share for Sheffield Scientific School! Gilman had, of course, tailored his report to fit the amount forthcoming for Connecticut. No other institution in Connecticut received even a whisper until 1893, when Storrs Agricultural College received a land grant. Of course it helped that a member of The Order, Augustus Brandegee ('49), was speaker of the Connecticut State Legislature in 1861 when the state bill was moving through, accepting Connecticut's share for Sheffield. Other members of The Order, like Stephen W. Kellogg ('46) and William Russell ('33), were either in the State Legislature or had influence from past service. The Order repeated the same grab for public funds in New York State. All of New York's share of the Land Grant College Act went to Cornell University. Andrew Dickson White, a member of our trio, was the key activist in New York and later became first President of Cornell. Daniel Gilman was rewarded by Yale and became Professor of Physical Geography at Sheffield in 1863. In brief, The Order was able to corner the total state shares for Connecticut and New York, cutting out other scholastic institutions. This is the first example of scores we shall present in this series -- how The Order uses public funds for its own objectives. And this, of course, is the great advantage of Hegel for an elite. The State is absolute. But the State is also a fiction. So if The Order can manipulate the State, it in effect becomes the absolute. A neat game. And like the Hegelian dialectic process we cited in the first volume, the Order has worked it like a charm. Back to Sheffield Scientific School. The Order now had funds for Sheffield and proceeded to consolidate its control. In February 1871 the School was incorporated and the following became trustees: Charles J. Sheffield Out of six trustees, three were in The Order. In addition, George St. John Sheffield, son of the benefactor, was initiated in 1863, and the first Dean of Sheffield was J.A. Porter, also the first member of Scroll & Key (the supposedly competitive senior society at Yale). How The Order Came To Control Yale University From Sheffield Scientific School The Order broadened its horizons. The Order's control over all Yale was evident by the 1870s, even under the administration of Noah Porter (1871-1881), who was not a member. In the decades after the 1870s, The Order tightened its grip. The Iconoclast (October 13, 1873) summarizes the facts we have presented on control of Yale by The Order, without being fully aware of the details: "They have obtained control of Yale. Its business is performed by them. Money paid to the college must pass into their hands, and be subject to their will. No doubt they are worthy men in themselves, but the many whom they looked down upon while in college, cannot so far forget as to give money freely into their hands. Men in Wall Street complain that the college comes straight to them for help, instead of asking each graduate for his share. The reason is found in a remark made by one of Yale's and America's first men: 'Few will give but Bones men, and they care far more for their society than they do for the college.' The Woolsey Fund has but a struggling existence, for kindred reasons." "Here, then, appears the true reason for Yale's poverty. She is controlled by a few men who shut themselves off from others, and assume to be their superiors ..." The anonymous writer of Iconoclast blames The Order for the poverty of Yale. But worse was to come. Then-President Noah Porter was the last of the clerical Presidents of Yale (1871-1881), and the last without either membership or family connections to The Order. After 1871 the Yale Presidency became almost a fiefdom for The Order. From 1886 to 1899, member Timothy Dwight ('49) was President, followed by another member of The Order, Arthur Twining Hadley (1899 to 1921). Then came James R. Angell (1921-37), not a member of The Order, who came to Yale from the University of Chicago where he worked with Dewey, built the School of Education, and was past President of the American Psychological Association. From 1937 to 1950 Charles Seymour, a member of The Order was President followed by Alfred Whitney Griswold from 1950 to 1963. Griswold was not a member, but both the Griswold and Whitney families have members in The Order. For example, Dwight Torrey Griswold ('08) and William Edward Schenk Griswold ('99) were in The Order. In 1963 Kingman Brewster took over as President. The Brewster family has had several members in The Order, in law and the ministry rather than education. We can best conclude this memorandum with a quotation from the anonymous Yale observer: "Whatever want the college suffers, whatever is lacking in her educational course, whatever disgrace lies in her poor buildings, whatever embarrassments have beset her needy students, so far as money could have availed, the weight of blame lies upon this ill-starred society. The pecuniary question is one of the future as well as of the present and past. Year by year the deadly evil is growing. The society was never as obnoxious to the college as it is today, and it is just this ill-feeling that shuts the pockets of nonmembers. Never before has it shown such arrogance and self-fancied superiority. It grasps the College Press and endeavors to rule in all. It does not deign to show its credentials, but clutches at power with the silence of conscious guilt." APPENDIX TO MEMORANDUM NUMBER ONE: THE ORDER IN THE YALE FACULTY

_______________ 1. George Wilson Pierson, YALE COLLEGE 1871-1922 (Yale University Press. New Haven. 1952) . Volume One, p. 5. 2. E.E. Slosson, GREAT AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES (New York, 1910) pp. 59-60. 3. Fabian Franklin, THE LIFE OF DANIEL COIT GILMAN (Dodd, Mead. New York, 1910), pp. 28-9.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||