|

AMERICA'S SECRET ESTABLISHMENT -- AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ORDER OF SKULL AND BONES |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

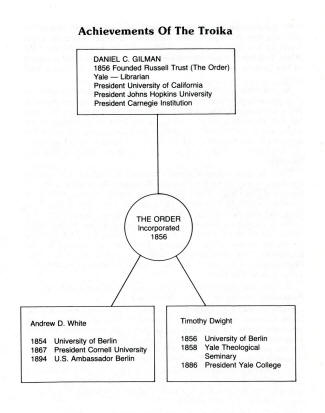

Memorandum Number Six: The Troika Spreads Its Wings Around the turn of the century The Order had made significant penetration into the educational establishment. By utilizing the power of members in strategic positions they were able to select, groom and position non-members with similar philosophy and activist traits. In 1886 Timothy Dwight (The Order) had taken over from the last of Yale's clerical Presidents, Noah Porter. Never again was Yale to get too far from The Order. Dwight was followed by member Arthur T. Hadley ('76). Andrew Dickson White was secure as President of Cornell and alternated as U.S. Ambassador to Germany. While in Berlin, White acted as recruiting agent for The Order. Not only G. Stanley Hall came into his net, but also Richard T. Ely, founder of the American Economic Association. Daniel Gilman, as we noted in the last memorandum, was President of Johns Hopkins and used that base to introduce Wundtian psychology into U.S. education. After retirement from Johns Hopkins, Gilman became the first President of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, D.C. The chart overleaf summarizes the achievements of this remarkable troika. Achievements of the Troika Now let's see how The Order moved into more specialized fields of education, then we need to examine how The Order fits with John Dewey, the source of modern American educational philosophy, then how The Order spread Dewey throughout the system. Founding Of The American Economic Association Academic associations are a means of conditioning or even policing academics. Although academics are great at talking about academic freedom, they are peculiarly susceptible to peer group pressures. And if an academic fails to get the word through his peer group, there is always the threat of not getting tenure. In other words, what is taught at University levels is passed through a sieve. The sieve is faculty conformity. In this century when faculties are larger, conformity cannot be imposed by a President. It is handled equally well through faculty tenure committees and publications committees of academic associations. We have already noted that member Andrew Dickson White founded and was first President of the American Historical Association and therefore was able to influence the constitution and direction of the AHA. This has generated an official history and ensured that existence of The Order is never even whispered in history books, let alone school texts. An economic association is also of significance because it conditions how people who are not economists think about the relative merits of free enterprise and state planning. State economic planning is an essential part of State political control. Laissez faire in economics is the equivalent of individualism in politics. And just as you will never find any plaudits for the Ninth and Tenth Amendments to the Constitution in official history, neither will you find any plaudits for individual free enterprise. The collectivist nature of present day college faculties in economics has been generated by the American Economic Association under influence of The Order. There are very few outspoken preachers of the Austrian School of Economics on American campuses today. They have been effectively weeded out. Even Ludwig von Mises, undisputed leader of the school, was unable to find a teaching post in the United States. So much for academic freedom in economics. And it speaks harshly for the pervasive, deadening, dictatorial hand of the American Economics Association. And the controlling hand, as in the American Psychological Association and the American Historical Association, traces back to The Order. The principal founder and first Secretary of the American Economic Association was Richard T. Ely. Who was Ely? Ely descended from Richard Ely of Plymouth, England who settled at Lyme, Connecticut in 1660. On his grandmother's side (and you have heard this before for members of The Order) Ely descended from the daughter of Rev. Thomas Hooker, founder of Hartford, Connecticut. On the paternal side, Ely descended from Elder William Brewster of Plymouth Colony. Ely's first degree was from Dartmouth College. In 1876 he went to University of Heidelberg and received a Ph.D. in 1879. Ely then returned to the United States, but as we shall describe below, had already come to the notice of The Order. When Ely arrived home, Daniel Gilman invited Ely to take the Chair of Political Economy at Johns Hopkins. Ely accepted at about the same time Gilman appointed G. Stanley Hall to the Chair of Philosophy and Pedagogy and William Welch, a member of The Order we have yet to describe, to be Dean of the Johns Hopkins medical school. Fortunately, Richard Ely was an egocentric and left an autobiography, Ground Under Our Feet, which he dedicated to none other than Daniel Coit Gilman (see illustration). Then on page 54 of this autobiography is the caption "I find an invaluable friend in Andrew D. White." And in Ely's first book, French And German Socialism, we find the following: "The publication of this volume is due to the friendly counsel of the Honorable Andrew D. White, President of Cornell University, a gentleman tireless in his efforts to encourage young men and alive to every opportunity to speak fitting words of hope and cheer. Like many of the younger scholars of our country, I am indebted to him more than I can say." Ely also comments that he never could understand why he always received a welcome from the U.S. Embassy in Berlin, in fact from the Ambassador himself. But the reader has probably guessed what Ely didn't know -- White was The Order's recruiter in Berlin. Ely recalls his conversations with White, and makes a revealing comment: "I was interested in his psychology and the way he worked cleverly with Ezra Cornell and Mr. Sage, a benefactor and one of the trustees of Cornell University." The reader will remember it was Henry Sage who provided the first funds for G. Stanley Hall to study in Germany. Then Ely says, "The only explanation I can give for his special interest in me was the new ideas I had in relation to economics." And what were these new ideas? Ely rejected classical liberal economics, including free trade, and noted that free trade was "particularly obnoxious to the German school of thought by which I was so strongly impressed." In other words, just as G. Stanley Hall had adopted Hegelianism in psychology from Wundt, Ely adopted Hegelian ideas from his prime teacher Karl Knies at University of Heidelberg. TO THE MEMORY OF DANIEL COIT GILMAN And both Americans had come to the watchful attention of The Order. The staff of the U.S. Embassy in Berlin never did appreciate why a young American student, not attached to the Embassy, was hired by Ambassador White to make a study of the Berlin City Government. That was Ely's test, and he passed it with flying colors. As he says, "It was this report which served to get me started on my way and later helped me get a teaching post at the Johns Hopkins." The rest is history. Daniel Coit Gilman invited Richard Ely to Johns Hopkins University. From there Ely went on to head the department of economics at University of Wisconsin. Through the ability to influence choice of one's successor, Wisconsin has been a center of statist economics down to the present day. Before we leave Richard Ely we should note that financing for projects at University of Wisconsin came directly from The Order -- from member George B. Cortelyou ('13), President of New York Life Insurance Company. Ely also tells us about his students, and was especially enthralled by Woodrow Wilson: "We knew we had in Wilson an unusual man. There could be no question that he had a brilliant future." And for those readers who are wondering if Colonel Edward Mandell House, Woodrow Wilson's mysterious confidant, is going to enter the story, the answer is Yes! He does, but not yet. The clue is that young Edward Mandell House went to school at Hopkins Grammar School, New Haven, Connecticut. House knew The Order from school days. In fact one of House's closest classmates at Hopkins Grammar School was member Arthur Twining Hadley ('76), who went on to become President of Yale University (1899 to 1921). And it was Theodore Roosevelt who surfaced Hadley's hidden philosophy: "Years later Theodore Roosevelt would term Arthur Hadley his fellow anarchist and say that if their true views were known, they would be so misunderstood that they would both lose their jobs as President of the United States and President of Yale." [1] House's novel, Philip Dru, was written in New Haven, Connecticut and in those days House was closer to the Taft segment of The Order than Woodrow Wilson. In fact House, as we shall see later, was The Order's messenger boy. House was also something of a joker because part of the story of The Order is encoded within Philip Dru! We are not sure if The Order knows about House's little prank. It's just like House to try to slip one over on the holders of power. American Medical Association Your doctor knows nothing about nutrition? Ask him confidentially and he'll probably confess he had only one course in nutrition. And there's a reason. Back in the late 19th century American medicine was in a deplorable state. To the credit of the Rockefeller General Education Board and the Institute for Medical Research, funds were made available to staff teaching hospitals and to eradicate some pretty horrible diseases. On the other hand, a chemical-based medicine was introduced and the medical profession cut its ties with naturopathy. Cancer statistics tell you the rest. For the moment we want only to note that the impetus for reorganizing medical education in the United States came from John D. Rockefeller, but the funds were channeled through a single member of The Order. Briefly, the story is this. One day in 1912 Frederick T. Gates of Rockefeller Foundation had lunch with Abraham Flexner of Carnegie Institution. Said Gates to Flexner: "What would you do if you had one million dollars with which to make a start in reorganizing medical education in the United States?" [2] As reported by Fosdick, this is what happened: "The bluntness was characteristic of Mr. Gates, but the question about the million dollars was hardly in accord with his usual indirect and cautious approach to the spending of money. Flexner's reply, however, to the effect that any funds -- a million dollars or otherwise -- could most profitably be spent in developing the Johns Hopkins Medical School, struck a responsive chord in Gates who was already a close friend and devoted admirer of Dr. William H. Welch, the dean of the institution." Welch was President of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research from 1901, and a Trustee of the Carnegie Institution from 1906. William H. Welch was also a member of the Order and had been brought to Johns Hopkins University by Daniel Coit Gilman. Other Areas Of Education We should note in conclusion other educational areas where The Order had its influence. In theology we have already noted that The Order controlled Union Theological Seminary for many years, and was strong within the Yale School of Divinity. The constitution for UNESCO was written largely by The Order, i.e., member Archibald MacLeish. And member William Chauvenet (1840) was "largely responsible for establishing the U.S. Naval Academy on a firm scientific basis." Chauvenet was director of the Observatory, U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis from 1845 to 1859 and then went on to become Chancellor of Washington University (1869). Finally, a point on methodology. The reader will remember from Memorandum One (Volume One) that we argued the most "general" solution to a problem in science is the most acceptable solution. In brief, a useful hypothesis is one that explains the most events. Pause a minute and reflect. We are not developing a theory that includes numerous superficially unconnected events. For example, the founding of Johns Hopkins University, the introduction of Wundtian educational methodology, a psychologist G. Stanley Hall, an economist Richard T. Ely, a politician Woodrow Wilson -- and now we have included such disparate events as Colonel Edward House and the U.S. Naval Observatory. The Order links to them all ... and several hundred or thousand other events yet to be unfolded. In research when a theory begins to find support of this pervasive nature it suggests the work is on the right track. So let's interpose another principle of scientific methodology. How do we finally know that our hypothesis is valid? If our hypothesis is correct, then we should be able to predict not only future conduct of The Order but also events where we have yet to conduct research. This is still to come. However, the curious reader may wish to try it out. Select a major historical event and search for the guiding hand of The Order. Members Of The Order In Education

_______________ 1. Morris Hadley. ARTHUR TWINING HADLEY, Yale University Press. 1948, p. 33. 2. Raymond D. Fosdick. ADVENTURE IN GIVING (Harper & Row. New York. 1962), p. 154.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||