|

THE CIA'S SECRET WAR IN TIBET -- CHAKRATA |

|

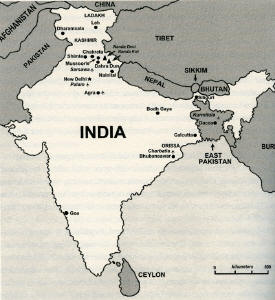

Chapter 13: Chakrata Jamba Kalden was a latecomer to the resistance. A successful Khampa trader from Chamdo -- the first town captured by the PLA during the invasion of October 1950 -- he had repeatedly turned a deaf ear to early recruitment calls from the NVDA. Not until early 1959, with tension in Lhasa reaching the breaking point, did he feel compelled to visit the capital. There the sight of raucous crowds surrounding the Dalai Lama's Norbulingka summer palace proved infectious, drawing the thirty-nine-year-old businessman into the midst of the swelling anti-Chinese protests. It was to prove a short and painful introduction to civil disobedience. On the morning of 20 March, two days after the Dalai Lama fled for the border, the PLA began shelling the palace. By that afternoon, hundreds of Tibetans lay dead or wounded. Attempting to evade the closing Chinese cordon, Jamba Kalden took a bullet to the thigh and was promptly arrested. He was confined to a small Lhasa cell while he nursed his wound, and not until summer was the injury sufficiently healed for him to be assigned to one of the prisoner gangs the Chinese had dispatched to various construction sites near the capital. Jamba Kalden did not take well to forced labor. His once impressive physique turned gaunt from the hard work and meager rations, and he began planning his escape toward year's end. Not until 17 January 1960 did he find the opportunity to slip away from his minders. He and two fellow prisoners made their way through blinding winter snowstorms toward the southern border. In May they reached Bhutan; two months later, they crossed into India. By that time, the Dalai Lama and his entourage had taken up residence in the town of Dharamsala. Situated 725 kilometers northwest of New Delhi in the Himalayan foothills, Dharamsala -- literally, "rest house" -- was once a traditional stop for Hindu pilgrims. By 1855, it had become a flourishing hill station for the British, only to see its popularity plummet after a devastating 1905 earthquake. Its last bloc of residents, a handful of Muslims, left for newly created Pakistan in 1947. For the Indian government, Dharamsala's remote location and lack of population were now its major selling points. Since the Dalai Lama had crossed onto Indian soil, he had made his temporary quarters near another former hill station, Mussoorie. But because Mussoorie was just a short drive from New Delhi, the monarch enjoyed easy access to the media limelight. Influential leaders such as Krishna Menon cringed at the young Tibetan's frequent and sympathetic contact with the press, leading them to propose more permanent -- and distant -- quarters at Dharamsala. With little choice, the Tibetan leader made the move in April 1960. If the Indians thought that Dharamsala was the answer to stifling the Dalai Lama, they were sadly mistaken. Using its isolation to his advantage, he converted the town into his de facto capital, then made good on his threats over the past year and began creating a government in exile. Part of this involved reforming the cabinet offices that previously existed in Lhasa. It also involved preparation of a draft constitution. At the same time, a straw vote was held in each of the main refugee camps over the summer. From this rudimentary selection process, thirteen representatives were chosen: three from each province, plus one for each of the four Tibetan Buddhist sects. Jamba Kalden arrived in Dharamsala as the thirteen delegates were convening for the first time in September 1960. In deference to his relative wealth and influential position back in Chamdo, he was anointed as a key adviser to the nascent government. He was still serving in this capacity in late October 1962 when Gyalo Thondup came looking for 5,000 volunteers to fill Brigadier Uban's tactical guerrilla force. Gyalo's task was not particularly complicated. As with the Mustang contingent, he was partial toward recruiting Khampas. Finding willing takers was no problem, as the patriotic call to duty -- and the chance for meaningful employment -- held great appeal among the refugee population. With word quickly spreading, volunteers by the thousands stepped forward over the ensuing weeks. Gyalo also sought four political leaders who could act as the force's indigenous officer cadre. Given his seniority, ethnicity, and proven aptitude in Dharamsala over the previous two years, Jamba Kalden was an easy first pick. By early November, an initial contingent of Tibetans, led by Jamba Kalden, was dispatched to the hill town of Dehra Dun. Once popular with Indian princes because of its mild climate, it later served as a key British educational center and military base. More recently it was host to the Indian military academy, a number of regimental barracks, and several prestigious boarding schools. Jamba Kalden had little time to appreciate Dehra Dun's climatic appeal. On hand to meet the Tibetans was Brigadier Uban and a skeleton staff of officers on loan from the army. While a transit tent camp was set up on the edge of town to process the 5,000 promised volunteers, on 14 November the Indian cadre and four political leaders shifted ninety-two kilometers northwest to the village of Chakrata. India Situated along a ridge and surrounded by forest glades, Chakrata had been chosen for good reason. Home to a thriving population of panthers and bears, it had once boasted two training centers for a pair of Gurkha regiments. Since 1960, however, both regiments had relocated to more favorable climes. [1] With almost no local residents and a set of vacant cantonments, Chakrata had both the ready facilities and the seclusion needed for the covert Tibetan project. Uban and his team settled in to await the arrival of the rest of the 5,000 volunteers by year's end and began mapping out the process of molding them into effective guerrillas. *** For intelligence chief Mullik, the Chakrata project signaled a new sense of militancy regarding Tibet. This was communicated in strong fashion on 29 December when Mullik -- through Gyalo Thondup -- told the Dalai Lama that New Delhi had now adopted a covert policy of supporting the eventual liberation of his homeland. Although the U.S. government did not match this with a similar pledge, the CIA wasted no time making good on its promise to help with the various Tibetan paramilitary schemes. As a start, Jim McElroy -- the same logistics expert who had been involved with ST CIRCUS since its inception, overseeing the air supply process from Okinawa and later helping with similar requirements at Camp Hale -- was dispatched to India in early January 1963. He was escorted by Intelligence Bureau representatives to the Paratroopers Training School at Agra, just a few kilometers from the breathtaking Taj Mahal palace. Because aerial methods would be the likely method of supporting behind-the-lines operations against the PLA, McElroy began an assessment of the school's parachute inventory to fully understand India's air delivery capabilities. He also started preliminary training of some Tibetan riggers drawn from Chakrata. McElroy's deployment paved the way for more substantial assistance. Stepping forward as liaison in the process was forty-seven-year-old Indian statesman Biju Patnaik. Everything about Patnaik, who stood over two meters tall, was larger than life. The son of a state minister from the eastern state of Orissa, he had courted adventure from a young age. At sixteen, he had bicycled across the subcontinent on a whim. Six years later, he earned his pilot's license at the Delhi Flying Club. Joining the Royal Air Force at the advent of World War II, he earned accolades after evacuating stranded British families from Burma. Other flights took him to the Soviet Union and Iran. Patnaik also made a name for himself as an ardent nationalist. Following in his parents' footsteps -- both of them were renowned patriots -- he bristled under the British yoke. Sometimes his resistance methods were unorthodox. Once while flying a colonial officer from a remote post in India's western desert region, he overheard the European use a condescending tone while questioning his skills in the cockpit. Patnaik landed the plane on a desolate stretch of parched earth and let the critical Englishman walk. [2] For actions like this, Patnaik ultimately served almost four years in prison. He was released shortly before Indian independence and looked for a way to convert his passion for flying into a business. Banding together with some fellow pilots, he purchased a dozen aging transports and founded a charter company based in Calcutta. He dubbed the venture Kalinga Air Lines, taking its name from an ancient kingdom in his native Orissa. Almost immediately, Patnaik landed a risky contract. Revolutionaries in the Indonesian archipelago were in the midst of their independence struggle, but because of a tight Dutch blockade, they were finding it hard to smuggle in arms and other essentials. Along with several other foreign companies, Kalinga Air Lines began charter flights on their behalf. It was Patnaik himself who evaded Dutch fighters to carry Muhammad Hatta (later Indonesia's first vice president) on a diplomatic mission to drum up support in South Asia. It was also through Kalinga Air Lines that Patnaik had his first brush with Tibet. By the mid- 1950s, he was looking to expand the airline through the acquisition of a French medium-range transport, the Nord Noratlas. He intended to use this plane for shuttles between Lhasa and Calcutta, having already purchased exclusive rights to this route. Before the first flight, however, diplomatic ties between India and China soured; Patnaik's license into Lhasa was canceled, and the air route never opened. Other ventures were more successful. Patnaik established a string of profitable industries across eastern India. And, like his father, he entered the government bureaucracy and eventually rose to chief minister -- akin to governor -- of his native Orissa. [3] In November 1962 -- during the darkest days of the Chinese invasion of NEFA -- Patnaik's patriotic zeal, taste for adventure, and brush with Tibet would all come together. As the PLA sliced through Indian lines, he rushed to New Delhi with an idea. The Chinese had overextended themselves in India, he reasoned, and therefore were vulnerable to a guerrilla resistance effort inside Assam. Given Patnaik's stature in Orissa, he was able to take his concept directly to Nehru. The prime minister listened and liked what he heard. By reputation, Patnaik had the charisma to carry out such an effort. At the very least, having the chief minister of one state take the lead in offering assistance to another state was good press. Patnaik was not the only one thinking along these lines. On 20 November, Mullik had notified Nehru that he wanted to quit his post as director of the Intelligence Bureau in order to focus on organizing a resistance movement in the event the Chinese pushed further into Assam. Nehru refused to accept his spy-master's resignation and instead directed him toward Patnaik, with the suggestion that they pool their talent. Meeting later that same afternoon, the spy and the minister became quick allies. Although their resistance plans took on less urgency the next day, after Beijing announced a unilateral cease-fire, Patnaik offered critical help in other arenas. Later that month, when the CIA wanted to use its aircraft to quietly deliver three planeloads of supplies to India as a sign of good faith, it was Patnaik who arranged for the discreet use of the Charbatia airfield in Orissa. And in December, after the CIA notified New Delhi of its impending paramilitary support program, he was the one dispatched to Washington on behalf of Nehru and Mullik to negotiate details of the assistance package. Upon his arrival in the U.S. capital, Patnaik's primary point of contact was Robert "Moose" Marrero. Thirty-two years old and of Puerto Rican ancestry, Marrero was aptly nicknamed: like Patnaik, he stood over two meters tall and weighed 102 kilos. He was also an aviator, having flown helicopters for the U.S. Marines before leaving military service in 1957 to join the CIA as an air operations specialist. As the two pilots conversed, they recognized the need for a thorough review of the airlift requirements for warfare in the high Himalayas. They also saw the need to train and equip a covert airlift cell outside of the Indian military chain of command that could operate along the Indo-Tibetan frontier. While Patnaik was discussing these aviation issues in Washington, the CIA's Near East Division was forging ahead with assistance for the Tibetans at Chakrata. Initially, the Pentagon also muscled its way into the act and in February 1963 penned plans to send a 106-man U.S. Army Special Forces detachment that would offer "overt, but hopefully unpublicized" training in guerrilla tactics and unconventional warfare. The CIA, meanwhile, came up with a competing plan that involved no more than eight of its advisers on a six-month temporary duty assignment. Significantly, the CIA envisioned its officers living and messing alongside the Tibetans, minimizing the need for logistical support. Given Indian sensitivities and the unlikely prospect of keeping an overt U.S. military detachment unpublicized, the CIA scheme won. [4] Heading the CIA team would be forty-five-year-old Wayne Sanford. No stranger to CIA paramilitary operations, Sanford had achieved a stellar service record in the U.S. Marine Corps. Commissioned in 1942, he had participated in nearly all the major Pacific battles and earned two Purple Hearts in the process -- one for a bullet to the shoulder at Guadalcanal, and the second for a shot to the face at Tarawa. Remaining in the Marine Corps after the war, Sanford was preparing for combat on the Korean peninsula in 1950 when fate intervened. Before he reached the front, a presidential directive was issued stating that anyone with two Purple Hearts was exempt from combat. Coincidentally, the CIA was scouting the ranks of the military for talent to support its burgeoning paramilitary effort on Taiwan. Getting a temporary release from active duty, Sanford was whisked to the ROC under civilian cover. For his first CIA assignment, Sanford spent the next eighteen months commanding a small agency team on Da Chen, an ROC-controlled islet far to the north of Taiwan. Part of the CIA operation at Da Chen involved eavesdropping on PRC communications. Another part involved coastal interdiction, for which they had a single PT boat. Modified with three Rolls Royce engines, self- sealing tanks, and radar, the vessel was impressive for its time. The ship's captain, Larry "Sinbad the Sailor" Sinclair, had made a name for himself by boldly attacking Japanese ships in Filipino waters during World War II; he continued the same daring act against the PRC from Da Chen. Eventually, the Chinese took notice. In methodical fashion, the communists occupied the islets on either side of Da Chen. Then shortly before Sanford's tour was set to finish, a flotilla of armed junks surrounded the CIA bastion, and bombers spent a day dropping iron from the sky. That night, the agency radiomen intercepted instructions for the bombers to redouble their attack at sunrise. Not liking the odds, Sanford ordered his CIA officers and remaining ROC troops -- thirty- seven in all -- into the PT boat. Switching on the radar, Sinclair ran the junk blockade under cover of darkness and carried them safely to the northern coast of Taiwan. [5] Returning to Washington, Sanford spent the rest of the decade on assignment at CIA headquarters. In October 1959, he ostensibly returned to active duty and was posted to the U.S. embassy in London as part of the vaguely titled Joint Planning Staff. In reality, the staff was a fusion of the CIA and the Pentagon; its members were to work on plans to counter various communist offensives across Eurasia. One such tabletop exercise involved a hypothetical Chinese invasion of South Asia. [6] By now a marine colonel, Sanford was still in London when the Chinese attack materialized and CIA paramilitary support for India was approved in principle in December 1962. Early the following year, after the CIA received specific approval to send eight advisers to Chakrata, Sanford was selected to oversee the effort. He would do so from an office at the U.S. embassy in New Delhi while acting under the official title of special assistant to Ambassador Galbraith. As this would be an overt posting with the full knowledge of the Indian government, both he and the seven other paramilitary advisers would remain segregated from David Blee's CIA station. Back in Washington, the rest of the team took shape. Another former marine, John Magerowski, was fast to grab a berth. So was Harry Mustakos, who had worked with the Tibetans on Saipan in 1957 and served with Sanford on Da Chen. Former smoke jumper and Intermountain Aviation (a CIA proprietary) rigger Thomas "T. J." Thompson was to replace Jim McElroy at Agra. Two other training officers were selected from the United States, and a third was diverted from an assignment in Turkey. The last slot went to former U.S. Army airborne officer Charles "Ken" Seifarth, who had been in South Vietnam conducting jump class for agents destined to infiltrate the communist north. [7] By mid-April, the eight had assembled in New Delhi. If they expected war greetings from their CIA colleagues in the embassy, it did not happen. "We were neither welcomed nor wanted by the station chief," recalls Mustakos. For Sanford, this was eventually seen as a plus. "Blee gave me a free hand," he remembered, "but Galbraith wanted detailed weekly briefings on everything we did." [8] At the outset, there was little for Sanford to report. Waiting for their gear to arrive (they had ordered plenty of cold-weather clothing), the team members spent their first days agreeing on a syllabus for the upcoming six months. One week later, their supplies arrived, and six of the advisers left Sanford in New Delhi for the chilled air of Chakrata. The last member, Thompson, alone went to Agra. Once the CIA advisers arrived at the mountain training site, Brigadier Uba gave them a fast tour. A ridgeline ran east to west, with Chakrata occupying saddle in the middle. Centered in the saddle was a polo field that fell off sharp to the south for 600 meters, then less sharply for another 300 meters. North of the field was a scattering of stone houses and shops, all remnants of the colonial era and now home to a handful of hill tribesmen who populated the village. To the immediate west of the saddle was an old but sound stone Anglican church. Farther west were stone bungalows previously used by British officers and their dependents. Most of the bungalows were similar, differing only in the number of bedrooms. Each had eighteen-inch stone walls, narrow windows, fireplaces in each room, stone floors, and a solarium facing south to trap the heat on cold days and warm the rest of the drafty house. Each CIA adviser and India officer took a bungalow, with the largest going to Brigadier Uban. [9] East of the saddle was a series of stone barracks built by the British a century earlier and more recently used by the two Gurkha regiments. These were now holding the Tibetan recruits. There was also a longer stone building once used as a hospital, a firing range, and a walled cemetery overgrown by cedar. The epitaphs in the cemetery read like a history of Chakrata's harsh past. The oldest grave was for a British corporal killed in 1857 while blasting on the original construction. Different regiments were represented through the years, their soldiers the victims of either sickness or various campaigns to expand or secure the borders. There was also a gut-wrenching trio of headstones dated within one month of one another, all children of a British sergeant and his wife." Myself the father of three," said Mustakos, "I stood there heartsick at the despair that must have attended the young couple in having their family destroyed." [10] Once fully settled, the CIA team was introduced to its guerrilla students. By that time, the Chakrata project had been given an official name. A decade earlier, Brigadier Uban had had a posting in command of the 22nd Mountain Regiment in Assam. Borrowing that number, he gave his Tibetans the ambiguous title of "Establishment 22." In reviewing Establishment 22, the Americans were immediately struck by the age of the Tibetans. Although there was a sprinkling of younger recruits, nearly half were older than forty-five; some were even approaching sixty. Jamba Kalden, the chief political leader, was practically a child at forty-three. As had happened with the Mustang guerrillas, the older generation, itching for a final swing at the Chinese, had used its seniority to edge out younger candidates during the recruitment drive in the refugee camps. [11] With much material to cover, the CIA advisers reviewed what the Indian staff had accomplished over the previous few months. Uban had initially focused his efforts on instilling a modicum of discipline, which he feared might be an impossible task. To his relief, this fear proved unfounded. The Tibetans immediately controlled their propensity for drinking and gambling at his behest; the brigadier encouraged dancing and chanting as preferable substitutes to fill their leisure time. [12] The Indians had also started a strict regimen of physical exercise, including extended marches across the nearby hills. Because the weather varied widely -- snow blanketed the northern slopes, but the spring sun was starting to bake the south -- special care was taken to avoid pneumonia. In addition to exercise, the Indians had offered a sampling of tactical instruction. But most of it, the CIA team found, reflected a conventional mind-set. "We had to unteach quite a bit," said Mustakos. [13] This combination -- strict exercise and a crash course in guerrilla tactics -- continued through the first week of May. At that point, classes were put on temporary hold in order to initiate airborne training. Plans called for nearly all members of Establishment 22 to be qualified as paratroopers. This made tactical sense: if the Tibetans were to operate behind Chinese lines, the logical means of infiltrating them to the other side of the Himalayas would be by parachute. T. J. Thompson with two Tibetan student riggers, Agra airbase, summer

1963. When told of the news, the Tibetans were extremely enthusiastic about the prospect of jumping. There was a major problem, however. Establishment 22 remained a secret not only from the general Indian public but also from the bulk of the Indian military. The only airborne training facilities in India were at Agra, where the CIA's T. J. Thompson was discreetly training a dozen Tibetan riggers. Because the Agra school ran jump training for the Indian army's airborne brigade, Thompson had been forced to keep the twelve well concealed. But doing the same for thousands of Tibetans would be impossible; unless careful steps were taken, the project could be exposed. Part of the CIA's dilemma was solved by the season. The weather in the Indian lowlands during May was starting to get oppressively hot, making the dusty Agra drop zones less than popular with the airborne brigade. Most of the Tibetan jumps were intentionally scheduled around noon -- the least popular time slot, because the sun was directly overhead. The Intelligence Bureau also arranged for the Tibetans to use crude barracks in a distant corner of the air base, further reducing the chance of an encounter with inquisitive paratroopers. As an added precaution, a member of Brigadier Uban's staff went to an insignia shop and placed an order for cap badges. Each badge featured crossed kukri knife blades with the number 12 above. The reason: after independence from the British, the Indian army had inherited seven regiments of famed Gurkhas recruited from neighboring Nepal. Along with four more regiments that transferred to the British army, the regiments were numbered sequentially, with the last being the 11th Gorkha (the Indian spelling of Gurkha) Rifles. On the assumption that most lowland Indians would be unable to differentiate between the Asian features of a Gurkha and those of a Tibetan, Establishment 22 was given the fictitious cover designation "12th Gorkha Rifles" for the duration of its stay at Agra. [14] To oversee the airborne phase of instruction, Ken Seifarth relocated to Agra. Five jumps were planned for each candidate, including one performed at night. Because of the limited size of the barracks at the air base, the Tibetans would rotate down to the lowlands in 100-man cycles. With up to three jumps conducted each day, the entire qualification process was expected to stretch through the summer. All was going according to plan until the evening before the first contingent was scheduled to jump. At that point, a message arrived reminding Uban that the Indian military would not accept liability for anyone older than thirty-five parachuting; in the event of death or injury, the government would not pay compensation. This put Uban in a major fix. It was vital for his staff to share training hazards with their students, and he had assumed that his officers -- none of whom were airborne qualified -- would jump alongside the Tibetans. But although they had all completed the ground phase of instruction (which had intentionally been kept simple, such as leaping off ledges into piles of hay), his men had been under the impression that they would not have to jump from an aircraft. Their lack of enthusiasm was now reinforced by the government's denial of compensation. When Uban asked for volunteers to accompany the guerrilla trainees, not a single Indian officer stepped forward. [15] For Uban, it was now a question of retaining the confidence of the Tibetans or relinquishing his command. Looking to get special permission for government risk coverage, he phoned Mullik that evening. The intelligence director, however, was not at home. Taking what he considered the only other option, Uban gathered his officers for an emergency session. Although he had no prior parachute training, he told his men that he intended to be the first one out of the lead aircraft. This challenge proved hard to ignore. When the brigadier again asked for volunteers, every officer stepped forward. Uban now faced a new problem. With the first jump set for early the next morning, he had a single evening to learn the basics. He summoned a pair of CIA advisers to his room in Agra's Clarkes Shiraz Hotel. Using the limited resources at hand, they put the tea table in the middle of the room and watched as the brigadier rolled uncomfortably across the floor. Imaging the likely result of an actual jump, Seifarth spoke his mind. At forty-seven years old, he was a generation older than his CIA teammates and just a year younger than Uban. Drawing on the close rapport they had developed over the previous weeks, he implored the brigadier to reconsider. [16] The next morning, 11 May, a C-119 Flying Boxcar crossed the skies over Agra. As the twin-tailed transport aircraft came over the drop zone, Uban was the first out the door, Seifarth the second. Landing without incident, the brigadier belatedly received a return call from Mullik. "Don't jump," said the intelligence chief. "Too late," was the response. [17] In the weeks that followed, the rest of Establishment 22 clamored for their opportunity to leap from an aircraft. "Even cooks and drivers demanded to go," recalled Uban. Nobody was rejected for age or health reasons, including one Tibetan who had lost an eye and another who was so small that he had to strap a sandbag to his chest to deploy the chute properly. [18] Nehru, meanwhile, was receiving regular updates on the progress at Chakrata. During autumn, with the deployment of the eight-man CIA team almost finished, he was invited to make an inspection visit to the hill camp. The Intelligence Bureau also passed a request asking the prime minister to use the opportunity to address the guerrillas directly. Nehru was sympathetic but cautious. The thought of the prime minister addressing Tibetan combatants on Indian soil had the makings of a diplomatic disaster if word leaked. Afraid of adverse publicity, he agreed to visit the camp but refused to give a speech. Hearing this news, Uban had the men of Establishment 22 undergo a fast lesson in parade drill. The effort paid off. Though stiff and formal when he arrived on 14 November, Nehru was visibly moved when he saw the Tibetans in formation. And knowing that the prime minister was soft for roses, Uban presented him with a brilliant red blossom plucked from a garden he had planted on the side of his stone bungalow. Nehru buckled. Asking for a microphone, the prime minister poured forth some ad hoc and heartfelt comments to the guerrillas. "He said that India backed them," said Uban, "and vowed they would one day return to an independent country." [19]

|

|