|

THE CIA'S SECRET WAR IN TIBET -- MUSTANG |

|

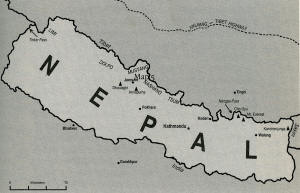

Chapter 11: Mustang Well before the parachute drop at Markham, the seeds of a new Tibet strategy were germinating. The impetus for this had come from NVDA chief Gompo Tashi and from Lhamo Tsering, Gyalo Thondup's able lieutenant in Darjeeling, who watched with concern as thousands of able-bodied Tibetan men were siphoned from Indian refugee camps and channeled into road construction gangs to help offset mounting aid costs. Some 4,000 ended up in Sikkim alone, where they were over- seen by a special relief committee headed by Princess Kukula. [1] Dispersing Tibetan manpower in this way put the two leaders in a quandary. Although having the refugees work on road construction was better than letting them languish in camps, employing large numbers of men as laborers sapped energy from the dream of retaking their homeland. Many of the displaced still clung to the hope of a resurgent NVDA, particularly older partisans who itched for the chance to take up arms one more time. Although neither Gompo Tashi nor Lhamo Tsering were opposed to the idea of a reborn guerrilla army, there was a serious geopolitical hurdle to overcome. To properly refit any irregulars, they needed a secure staging area. Given Nehru's continued desire to refrain from provoking the Chinese leadership, use of India for this purpose was out of the question. Similarly, Bhutan and Sikkim were too firmly under India's thumb to consider their territory as host for a significant paramilitary endeavor. By default, that left Nepal. A lone Hindu kingdom in the Buddhist Himalayas, Nepal was a study in selective nonalignment. For the first eight years of India's independence, Kathmandu had tempered its neutrality with a pro-Indian bias. At the same time, Nepal liked to think of Tibet (with considerable hyperbole) as a kind of vassal and not as part of China. But in 1955, with the death of mild King Tribhuwan and the rise of bolder son Mahendra, change was in the air. In an attempt to break what he saw as overdependence on India and to diversify the kingdom's foreign policy, the new king established diplomatic relations with the PRC in 1956 and signed a Sino-Nepalese trade agreement that same year. Although Kathmandu had moved a small step closer to Beijing -- and now recognized the PRC's hold over Tibet -- Gompo Tashi and Lhamo Tsering still had good reason to see Nepal as an attractive stepping-stone into their homeland. First, transportation difficulties and sharp ethnic differences meant that Kathmandu's grip barely reached outside the capital. Second, Nepal was already home to a large number of recent Tibetan arrivals. Estimates placed the number of refugees at 20,000 during the first two years of the Dalai Lama's exile. Of these, many were from the western reaches of Tibet and sought sanctuary in Nepal's most remote border areas, where Kathmandu's writ was rarely heard, much less acknowledged. [2] Third, one corner of Nepal -- the enclave of Mustang -- was for all intents and purposes part of Tibet. The highest kingdom in the world (with an average altitude of 3,758 feet), Mustang encompassed 1,943 square kilometers of arid gorges and cliffs centered along Nepal's northern border. Surrounded on three sides by Tibet, its population and culture were entirely Tibetan Buddhist. It had never been conquered by Nepal and, located north of the Himalayas, intuitively should have been incorporated under Lhasa's control. But after an eighteenth-century debt swap among highland royalty, Mustang passed to Nepal as a loose tributary. [3] Nepal could be forgiven for hardly noticing its new territorial addition. Led by its own line of kings dating back to the fourteenth century, Mustang consisted of just twelve large villages and the walled capital of Lo Monthang, where a modest palace was centered in a maze of temples and homes for 800 residents. Though it had once been prosperous -- thanks to its command over the salt trade into western Tibet -- Mustang had degenerated into a backwater after competing principalities to the south broke that monopoly in 1890. Despite its impoverishment, Mustang retained something more important: its autonomy. Even when Kathmandu insisted on the disbandment of other royal fiefdoms within its borders, Mustang alone was allowed to keep its king. In return for a token annual tribute of two horses and forty-five British pounds, Lo Monthang enjoyed near complete leeway in running its own affairs. [4] Besides its quasi-independence, there were other reasons for Lhamo Tsering and Gompo Tashi to favor Mustang. First, it was there that the Lithang Khampa team had fled in late 1959 after its abortive mission to Nam Tso; in messages sent back to Darjeeling, the agents had reported that their ethnic kin were generally supportive. Second, the border between Mustang and Tibet did not have any high passes blocked by snow in winter. Third, although its climate was dry and the land largely infertile, there was a handful of valleys with enough tree cover to camouflage a guerrilla encampment during the summer. Fourth, its remote location kept it out of range of foreign visitors; only one Western interloper had ever set foot in the region as of 1960. And if that were not enough, a divination arranged by the two leaders confirmed the choice of Mustang as a good one. [5] Nepal Although Gompo Tashi and Lhamo Tsering (who, it was understood, carried Gyalo's consent) were swayed that Mustang was a sure bet for a guerrilla sanctuary, the United States had to be convinced. Traveling to Calcutta in February 1960 to meet with CIA liaison officers, the two lobbied for support of their Nepal plan. At the time, Washington's relations with Kathmandu could only be described as cool and proper. This was largely due to King Mahendra's engagement policy of playing off the major powers, milking aid from all but not endearing himself to any. Had the United States requested permission from Mahendra to use Mustang, it is unlikely that it would have been granted. [6] But the question was never asked. Just as Gompo Tashi and Lhamo Tsering had calculated, poor transportation and communication networks severely curtailed the Nepalese government's extent of control. "Most ministers had never seen their own country," noted one American aid worker who served there in 1960." [7] Concluded Ralph Redford, the CIA station chief in Kathmandu, "The king's permission was not necessarily required." [8] Once word of the pitch from the two Tibetans reached Washington, the CIA's task force officers quickly concurred that a modest guerrilla operation staged from Mustang had merit and would not irreparably harm U.S.-Nepal relations. Gompo Tashi was given approval in March to begin the process of identifying candidates to lead the paramilitary force. Rushing north to Kalimpong, the ailing chieftain beckoned seven senior NVDA officers for three days of intense discussion. Informed of the pending Mustang operation, they were told to choose a field commander from among their number. Even for a people used to a challenging lifestyle, the assignment promised to be a hardship tour. Gompo Tashi, though the logical choice, was ineligible because he required too much rest and care. Similarly, six others withdrew themselves from consideration due to age or poor fitness or because they had dependents. The only one remaining, forty-three-year-old Baba Yeshi, received their unanimous support. As suggested by his name, Baba Yeshi hailed from the central Kham town of Raba (now called Bathang). Due to its relatively low altitude, Bathang was an early target for Han colonization and had even attracted French missionaries during the early twentieth century. The locals had strongly resisted these ethnic and religious incursions. The missionaries ultimately withdrew after several priests were executed, but the Chinese battled back and held on until mid century. By the time of the 1956 uprising, the Khampas of Bathang were primed to explode. Among the first to revolt, they courted a harsh PLA response. Chinese aircraft rained down bombs, paying special attention to monasteries. One such destroyed temple was the home of Raba Yeshi, who had entered the priesthood at age eight and took his vows at eighteen. Though from a poor family, the monk had shown a talent for trading cloth and had amassed respectable savings. Predicting more Chinese attacks to come, he gathered his inventory and made his way to the safer climes of Kalimpong. The respite was not to last. By mid-1958, word of the newly christened NVDA quickly filtered down to India. Prodded by other exiles, Baba Yeshi agreed to return to Tibet on the pretext of a pilgrimage. His real purpose was to help raid an armory near the Nepalese border. He attempted to do so, but the Tibetan army held firm and refused to release the weapons. Dejected, he headed toward Drigu Tso lake to link up with Gompo Tashi, only to find that the chieftain had already shifted to the north. Baba Yeshi, the first commander of Mustang. (Courtesy Roger MacCarthy) He remained in the vicinity of Drigu Tso, and by the fall of 1958, Baba Yeshi was elected leader of a large, albeit quiet, NVDA sector. By his own admission, they accomplished little. "I had no military background," he later recounted, "and just one in ten of my guerrillas had a weapon." Their biggest excitement came the following spring, when they received couriered orders to secure the area north of the lake during the passage of the fleeing Dalai Lama. [9] Not until after the Dalai Lama reached India did Baba Yeshi at long last rendezvous with Gompo Tashi. But by that time, the NVDA chief was also on his way to exile. Baba Yeshi joined him and crossed the border, where he stewed in a refugee camp for the next eight months. Frustrated by the boredom and the heat, the monk finally saw an opportunity for action in December 1959. With Eisenhower set to make the first visit to India by a U.S. president, he and fourteen other Khampa leaders rushed down to New Delhi and stood along Eisenhower's motorcade route in an attempt to hand him a letter calling for U.S. support. Not surprisingly, the Khampas came nowhere close to getting an audience with the visiting dignitary. Dejected again, Baba Yeshi returning to the steaming refugee camp and was still there when he got the call from Gompo Tashi to come to Kalimpong. When he learned of the impending Mustang operation -- and got the unanimous support of his peers to lead it -- Baba Yeshi was more than a little apprehensive. He was the first to admit that he had no formal military training. And despite his years studying Buddhist scripture, his writing skills were poor. There was also the controversy surrounding his hometown, Bathang. Owing to its long occupation by the Chinese, Bathang was infamous for its Khampa sympathizers and informants. Bathang also hosted a large number of Muslim Hiu, many of whom had assisted Beijing in battles against tile Tibetan resistance. This, plus petty rivalries with neighboring towns such as Lithang, gave Bathang residents the reputation for being antagonistic toward their countrymen. [10] But Baba Yeshi had other qualities that offset such deficiencies. In a culture not known for oratory, he was renowned as an articulate public speaker who exuded emotion and could even bring up tears on cue. As a monk, he had no dependents. And he was also known for his keen ability to anticipate and resolve problems within his ranks. "He was nicknamed Cat," said one of his subordinates, "because he would pounce on trouble like catching a mouse." [11] Upon confirmation of Baba Yeshi as overall leader, Gompo Tashi and Lhamo Tsering made the rounds of the various refugee camps to select another two dozen candidates to serve as a U.S.-trained officer cadre for the guerrilla force. The choice was limited to NVDA veterans without dependents and in good physical condition. To maximize clan coverage, no more than two men were chosen from each large district (such as Lithang), and only one from small districts. [12] When the final cut was made in May, twenty-seven candidates had assembled in Darjeeling. Reflecting the composition of the NVDA, as well as the makeup of the refugee pool, only two were from Amdo; the rest were from Kham. Most were in their mid-thirties, although four were close to fifty years of age. They were told the nature of their assignment in general terms, but not the location. [13] Before getting to Mustang, there remained the matter of training. Escorted by Lhamo Tsering to the East Pakistan frontier, the twenty-seven approached the rain-swollen river defining the border. They crossed it with difficulty and were deluged by heavy June rains for the entire bus and train ride to Dacca. Not until one week later were they back in their element among the mountains of Colorado. [14] As leader of the Mustang force, Baba Yeshi had a whirlwind schedule prior to departure for the front. First was a plane ride to meet CIA representatives in Calcutta, followed by a stop in Darjeeling for an audience with Gyalo Thondup. After that was a trip to Siliguri to rendezvous with two CIA-trained Tibetan radio operators. [15] Then came the long trek into Nepal. From Siliguri, the monk and two radiomen -- plus a Tibetan guide provided by Gyalo -- took a train west to the Indian city of Gorakhpur, then a bus north to Kathmandu. There they rented a room near the huge Swayambhunath stupa, one of the holiest Buddhist shrines in Nepal, situated atop a hillock on the capital's western outskirts. For two weeks, they waited near the stupa. Unknown to the Tibetans, a storm brewing within the CIA was causing delays. So as not to burden Baba Yeshi with heavy equipment during his trip into Nepal, the Tibet Task Force had intended to pass him three radio sets after his arrival in Kathmandu. Kenneth "Clay" Cathey, a CIA officer based in Calcutta, had been charged with overseeing the transfer. Helping him would be Ray Stark, the former Hale radio instructor beckoned from an assignment in Manila. [16] Unfortunately for Cathey and Stark, the CIA station in Nepal was doing all it could to stymie the transfer plan. Backed by Near East Division colleagues in New Delhi and at headquarters, station chief Redford opposed the scheme because he did not want to risk exposure on his home turf. Only after explicit instructions from the office of Director Dulles did the Nepal embassy reluctantly cooperate. Following this high-level directive, the three radios arrived in Kathmandu in a diplomatic pouch. To make them portable, Stark helped break them into forty smaller loads. Cathey then procured some plain burlap and, because the station chief refused to lend his men to assist, was forced to spend an extra day wrapping the equipment on his own. By that time, Lhamo Tsering and another Tibetan radioman had arrived in Kathmandu to help with the radio delivery. Because it was too risky to have Baba Yeshi come to the embassy, they needed to bring the gear to him. The station chief, still intent on obstructing the plan, insisted on using a taxi, but Cathey eventually persevered in getting loan of an embassy jeep. That night, Cathey, Lhamo Tsering, and the radioman drove with the dissembled communication equipment to a darkened corner of the Swayambhunath stupa. Baba Yeshi, his two radiomen, and eighteen more Khampas that had joined the party made the rendezvous. There they split in two, with a pair of the radiomen and twelve of the Khampas securing the radios on their backs and setting off on foot in the direction of Mustang. After giving them a five-day lead, Baba Yeshi, the remaining radioman, and six other Khampas attempted to get plane tickets for Pokhara, 130 kilometers west of Kathmandu and just south of Mustang. But to Baba Yeshi's chagrin, the sales representatives for Royal Nepal Airlines were extremely suspicious, even after the monk showed Tibetan documents that "proved" they were heading to Pokhara to help fellow refugees. Such suspicion was understandable. Tibetan exiles were doing all they could to leave Pokhara, not the other way around. There was also the matter of increased tensions along the Sino-Nepalese frontier. Beijing had recently closed its border to grazing on the Chinese side, previously a common practice among Nepalese herders. More seriously, a PLA patrol had crossed the border into Mustang during June, apparently believing that it had spotted Khampa guerrillas. In the ensuing skirmish, they killed a Nepalese soldier and took ten civilians prisoner, sending a wave of panic through Lo Monthang. [17] Ten days later they were still without plane tickets, and Baba Yeshi and his men thought it prudent to leave the Nepalese capital. Making their way back to Gorakhpur, they took a train northeast along the border, then recrossed into Nepal from the frontier town of Bhadwar. From there, it was a five-day trek on foot to Pokhara. Fearful that the Nepalese authorities might have been alerted, they wasted no time walking another four days up narrow paths to the village of Tukuche. In a kingdom full of breathtaking vistas, Tukuche ranked high among them. Situated in a gap in the Himalayas where the Kali Gandaki River flows through the Annapurna and Dhaulagiri Mountains, it is bracketed by canyon walls rising five kilometers on either side. By the time Baba Yeshi arrived there, the party that had departed Kathmandu on foot was already waiting in tents and had established radio contact with Darjeeling. [18] Hearing of the successful rendezvous at Tukuche, Lhamo Tsering assembled the first group of guerrilla prospects from the Indian refugee camps. Earlier, Gompo Tashi had talked in terms of eventually building a 2,100-man force, but the CIA had approved support for only 400. Making the selection at Darjeeling, Lhamo Tsering gave each approved recruit a pair of shoes and a small rupee stipend to pay for food on the trip through Nepal. It was a relatively old crowd, with most close to forty years of age. Nearly all were Khampas. Very quickly, word of the recruitment flashed among the refugees. What was supposed to be a clandestine shift of personnel suddenly became a very public one. On 1 August, the Indian media in Calcutta reported on the mysterious exodus of Tibetan men out of Sikkim. By early fall, Lhamo Tsering's 400 approved candidates were joined in Nepal by 200 unapproved Tibetans; several hundred others were on the way. [19] With Tukuche fast growing crowded, Baba Yeshi sent three men north to make a ten-day reconnaissance trek for suitable locations inside Mustang. By October, they had returned with a pair of recommendations. The first was Yara, little more than a cluster of earthen huts situated in a fertile valley dotted with conifers and tucked under a massive cliff honeycombed with caves. The second, twelve kilometers southwest of Yara, was Tangya. Sited in one of the lowest valleys in Mustang, it was packed with barley fields and, like Yara, was in the shadow of an imposing cliff eroded like the flutes of an organ. Both were east of the Kali Gandaki and several days' hike from the other major villages in Mustang. [20] Baba Yeshi started dispatching recruits to the Yara valley. In November, he himself made the shift from Tukuche to Tangya. With no weapons, a handful of tents, and little food, the prospective guerrillas and their leader settled in for the long, cold winter. [21] *** On the other side of the world at Camp Hale, the Mustang leadership cadre spent the winter of 1960-1961 training alongside the agent team destined for Markham. Despite the advanced age of several in the group, the twenty-seven were put through all their paramilitary paces. No problems were encountered -- with one near-fatal exception. Prior to making actual airborne jumps at Fort Carson, the Tibetans practiced in a training rig at Hale nicknamed Suspended Agony. It consisted of webbing hanging from a makeshift iron frame, and the students needed to climb a ramp to get into the parachute harness. Suspended Agony had worked well with earlier classes, but by the time the Mustang group arrived, it was showing its age. Unfortunately for Namgyal, a forty-five-year-old Bathang native who went by the call sign "Sampson," the iron frame decided to snap while he was in it. Dropping two meters to the ground, Sampson collapsed as the metal sliced into his forehead, exposing his skull. [22] The CIA instructors rushed to the side of the unconscious Sampson, loaded him into a station wagon, and sped him to the army hospital at Fort Carson. There the doctors did not give him a good prognosis. "There was no way we could bring the body back to Tibet," said Sam Poss, "so talk shifted to getting lime and burying him back at Hale." But it never came to that. Showing far more resilience than the doctors thought possible, Sampson made a miraculous recovery. Returning to Hale, he eventually completed his airborne training in the spring of 1961. By that time, his peers had graduated and been fully briefed on their impending mission to Mustang. The CIA's task force officers had been particularly impressed by Lobsang Jamba, a forty-year-old Lithang Khampa using the call sign "Sally." According to revised plans, Sally would parachute into Mustang and assume the role of field commander inside Tibet; Baba Yeshi, meanwhile, would be relegated to administrative chief at the Tangya rear base. [23] Back in Nepal, Baba Yeshi had not yet been informed of this new leadership arrangement. His attention had been fixated on the dire food situation at his guerrilla camp. As longtime Mustang residents well knew, the infertile kingdom could not stockpile enough food to feed all its people through winter. For that reason, just 35 percent of the population of Lo Monthang (primarily the elderly) remained in town year-round; the remainder migrated for the coldest months down to Pokhara. [24] When Baba Yeshi showed up at Tangya in November 1960, neither he nor his men at Yara had brought any food with them. They also carried little cash to purchase tsampa and other essentials. And even if they had brought money, more than 1,000 would-be guerrillas had assembled at Yara by year's end, far out-stripping the amount of staples that valley could produce. Very quickly, malnutrition reached critical levels. In desperation, more than a few boiled shoe leather for a meal. [25] Compounding matters, the CIA still did not have permission to make a supply drop, due to the prohibition against overflights following the U-2 affair. And if that were not enough, the new Kennedy administration was divided over whether the Mustang plan should even proceed. Heading the resistance was the new U.S. ambassador to India, John Kenneth Galbraith. A Canadian immigrant, Galbraith was an influential name in liberal circles. As a former Harvard professor of Keynesian economics, price czar during World War II, and editor of Fortune magazine, he had been an adviser to all Democratic presidents since Franklin Roosevelt. A prolific writer, Galbraith was renowned for his eloquent prose. He was also known for his grand ego, and as part of Kennedy's Harvard brain trust, he considered himself a logical pick for secretary of state. But Kennedy had other ideas. It was widely known that both he and Galbraith shared a strong pro- India bias. As senator, Kennedy had spoken of India as a key to Asia. An economically strong India, went his argument, would be an essential showpiece for democracy in the Third World and a fitting challenge to Chinese communism in Asia. Although Eisenhower had stopped seeing Indian neutralism as evil by 1958, and his 1959 trip to New Delhi had been a resounding success, Kennedy felt that his predecessor had all but lost India through the misplaced goal of cultivating Pakistan. [26] Based on this conviction, Kennedy was quick to place several well-known India supporters in important positions. Chester Bowles, a former ambassador in New Delhi, had been his foreign policy adviser during the campaign. Phillips Talbot, a scholar-journalist who specialized in things Indian, became assistant secretary of state for Near East and South Asian affairs. And on 29 March 1961, Galbraith was appointed the new ambassador to India. Shortly before his departure for New Delhi, the ambassador-designate went to CIA headquarters for a briefing on intelligence operations in India, as well as on the fledgling guerrilla force in neighboring Nepal. Heading the briefing was Richard Bissell, chief of covert operations, who, like Galbraith, had once been an Ivy League professor of economics. Joining Bissell was Far East chief Des FitzGerald, the Tibet operation's most die-hard and senior proponent, and James Critchfield, FitzGerald's counterpart in the Near East Division. [27] After reviewing the CIA's planned budget for throwing India's upcoming elections, Galbraith was not amused. But it was upon hearing the details of the Mustang scheme that Galbraith became livid. Pushing back his chair, he stood up and glared at the CIA officers. "This sounds like the Rover Boys at loose ends," said the soon-to-be diplomat before stalking out. [28] Galbraith's seething opposition was apparently grounded in his belief that the Tibet operation's benefits -- especially from the Mustang component -- did not outweigh the risk of harm to Indo-U.S. relations. He was especially sensitive to U.S. violations of Indian airspace in the extreme northeast during resupply flights, which he felt were as potentially destructive as the U-2 affair. Galbraith further claimed that his predecessor, Ellsworth Bunker, strongly shared his opposition. [29] The new ambassador was overstating fears, if not inventing a few. Had Ambassador Bunker indeed been opposed during his tenure, he had never protested too loudly. The Indians, too, seemed more than willing to turn a blind eye on the CIA's cavorting with the Tibetans. In 1960, B. N. Mullik, head of the Indian Intelligence Bureau, and Richard Helms, the CIA's chief of operations for the Directorate of Plans, had met discreetly during an Interpol conference in Hawaii; at that time, Mullik said that he endorsed the agency's efforts and wanted U.S. overflights to continue. [30] Galbraith's real opposition, suspected several in the CIA, was based as much on genuine diplomatic concerns as on his anti-CIA slant, especially toward an operation initiated during the previous Republican administration. [31] But Galbraith was hardly alone. Even within the CIA, opposition to the Tibet project was evident. This had less to do with arguments over the operation's potential yield than turf battles between the agency's geographic divisions. At the level of division chief, there was little friction between the Far East's FitzGerald and the Near East's Critchfield. For his part, Critchfield was largely indifferent toward Tibet. A longtime Europe hand (he had started his agency career handling Reinhard Gehlen, the former Nazi general co-opted by the CIA for his anticommunist intelligence network) , Critchfield was an Asia novice when he was picked by Dulles in late 1959 to command the Near East. [32] By that time, the Tibet Task Force was already making regular use of India and East Pakistan. "I had zero veto power over the Tibet operation," Critchfield recalled, "even when it involved overflights of India." Only when Tibetan trainees were set to pass through Near East territory in East Pakistan was he given a courtesy alert. [33] Although Critchfield did not find this particularly problematic, the same could not be said for others in his division. Heading that list was the CIA station chief in New Delhi, Harry Rositzke. The Harvard-educated professor and OSS alumni had been in India since May 1957. "Rositzke was strong minded, fast talking, and thought of himself as a world thinker," said one case officer who served under him. "He seemed to envision himself going back to Harvard one day, not as an agency career man." [34] The ambitious Rositzke did not appreciate hosting part of an operation that earned him no credit in Washington but would leave him reaping bad publicity if things went sour. "The Far East Division got all the kudos," said one India case officer, "but the Near East Division risked the potential embarrassment." [35] Rositzke's displeasure with this arrangement was focused squarely on the Far East Division's liaison officer in Calcutta, John Hoskins. Since 1956, Hoskins had been point man for dealings with Gyalo Thondup. As long as those dealings were low-key, New Delhi station had not complained too loudly. But once the Dalai Lama went into exile and the Tibet Task Force shifted into high gear, New Delhi's fear of a diplomatic incident rose accordingly. Insistent that Hoskins minimize any risk taking, the New Delhi station lobbied against his right to dispatch cables directly to headquarters. As a compromise, it was agreed that Hoskins would channel his communications through New Delhi, although Rositzke was not allowed to alter or edit the contents. Despite striking this deal, Hoskins could not help but feel that he was under growing pressure. Even though he ultimately answered to the Far East Division, it was the Calcutta chief of base -- a Near East officer -- who wrote his annual performance reviews, which carried a lot of weight when it came to promotions. Fearful that his career would suffer, he approached the Near East Division in the summer of 1959 and asked if he could keep his Calcutta post but transfer under its mantle. With the request quickly approved, Hoskins continued to handle Gyalo, but now under Rositzke' s complete control. Having lost its own representative in Calcutta, the Far East Division was not about to concede in the turf war. In order to keep tabs on Hoskins, in September 1959 it insisted on assigning a Far East officer to the New Delhi embassy. That officer, Howard Bane, was senior to Hoskins and in theory would act as the primary point of contact with Gyalo. In addition, the CIA had started contributing a stipend for the Dalai Lama and his entourage -- "providing them with rice and robes," said Hoskins -- and Bane was in charge of the purse. [36] Very quickly, Bane began to experience the same pressures Hoskins had endured before his transfer. Located within the same embassy as the assertive Rositzke, Bane realized that his career interests hinged on keeping the peace with the station chief. His muted cables back to the Far East Division reflected this accommodation. Back in Washington, FitzGerald fumed over not having an aggressive division representative in India. In February 1960, he used his pull with Dulles and successfully lobbied for the stationing of yet another officer, this time to Calcutta to fill the gap left by Hoskins. Chosen for the post was Vanderbilt doctoral graduate Clay Cathey. So as not to repeat the "loss" of Bane, Cathey was briefed "up to his eyeballs" by Tibet Task Force officers McCarthy and Greaney prior to his departure the following month. "They reminded me that I worked for the Far East Division," he said, "and not to do anything just because the Near East tells me to." As had the others before him, Cathey quickly felt the strain of the interdivision rift over Tibet. Though he remained true to his division ("He was the only one who supplied us with good information," said Greaney), Rositzke did not make the job easy. Every three months, the station chief ordered him to New Delhi for an intense grilling session. Cathey was extremely cautious about what he said, having been warned that the testy former Harvard professor would use whatever he could to shut down the project. "Rositzke did not see himself as a career man," explained Cathey, "so even if the Tibet program held favor with Dulles, he felt no need to please the director. " [37] *** Despite simmering opposition from the likes of Rositzke and Galbraith, President Kennedy in the second week of March 1961 approved an initial supply drop to Mustang. It was scheduled for the end of the month during the full moon phase and would total 29,000 pounds of arms and ammunition for 400 men. The bulk of the load was to consist of bolt-action Springfield rifles, plus forty Bren light machine guns and a mix of forty MI Garands and carbines. Also included in the drop would be seven Hale graduates. Four were from the pool of twenty-seven Mustang leaders, including field commander-designate Sally. The remaining three were radiomen, all ethnic Khampas. [38] They flew to Okinawa on the same plane as the Markham team and then waited a week on the island for weather conditions along the Nepal border to clear. Not until the last day of March did they continue on to Takhli. Sally remembers his final briefing: "The CIA said that the Chinese might have gotten to the drop zone. If so, I was to use my Sten submachine gun. If I finished those bullets, I was to use my pistol. If that was finished, I was to bite my cyanide." [39] Back at Tangya, Baba Yeshi's radiomen had already received word of the impending drop. Eight hundred men, led by Baba Yeshi himself, shifted fifteen kilometers northeast to the border, then another ten kilometers deeper into Tibet. Given the snow and terrain, this translated into a two-day trek. As they had no beasts of burden, 600 of this number were to act as porters; the remaining 200, having borrowed a handful of antiquated rifles from local herders, were to act as a paltry security force in the event of a PLA attack. [40] Once at the designated drop zone, the reception committee arranged piles of yak dung to serve as fuel for flame signals. Unfortunately for them, atmospheric conditions frustrated further radio contact with Takhli for two days. With the seven agents and supplies grounded in Thailand for an extra forty-eight hours, dozens among the 800 suffered frostbite. Not until the evening of 2 April did the radio prove cooperative, and an all-clear signal was conveyed to the launch site. Due to the large size of the load, supplies had been divided between two Hercules transports. Even then, the seven agents barely had room to sit as they boarded the first aircraft. This, combined with the extreme distance, made for an exhausting albeit uneventful flight. Sighting the flame signals on the ground, the Air America crews continued deeper into Tibet, then circled around for a second pass. In the rear, a nervous Sally was the first out the door. Landing in snow up to his waist, he worked quickly to get clear of the pallets that followed. Porters soon swarmed over the bundles, securing them on their backs before beginning the arduous journey back to Mustang. *** Although the drop was a success -- and the Indians had not indicated any knowledge of, much less displeasure with, the brief intrusion into their airspace- -- Ambassador Galbraith was more determined than ever to close the Mustang project. Traveling to Washington in May, he played on his rapport with Kennedy (who was already incensed with Dulles over the Bay of Pigs fiasco in April) to lobby the president for an end to what he saw as CIA interference. But even though the ambassador was able to stop most of the agency's covert operations inside India, he failed to put a damper on the Tibet project. [41] Ironically, Galbraith was about to get an unlikely ally in the form of the Pakistani government. During the course of the Eisenhower presidency, the CIA had enjoyed cordial ties with Karachi. This included permission to use not only East Pakistani territory for the Tibet operation but also an airfield near the city of Peshawar as a U-2 launch site. Even when it was publicly revealed that the U-2 downed in May 1960 had originated from that airfield, Karachi hardly registered any protest over the resultant embarrassment. But these warm ties looked set to change with the election of Kennedy and the pro-India bias he brought to office. Pakistani concerns seemed confirmed in April 1961 when Washington pledged a staggering $1 billion in economic aid for India's upcoming five-year development plan. Even more troubling for Karachi, the new administration, citing a threat from China, agreed to sell 350 tanks to New Delhi at low rates. Pakistan wanted to retaliate, but it saw few ready options. It could not slam the door on Washington's military and economic assistance, because there were few alternative sources of aid that matched U.S. largesse. And it would do no good to withhold permission to use the Peshawar air base, because U-2 flights were still suspended. With little other choice, the Pakistanis closed their border for the Tibet project. For the Tibet Task Force, the timing could not have been worse. Twenty-three Mustang leaders (the four others had jumped on 2 April) were still at Hale awaiting word to return. Because the onset of the monsoon season prevented further parachute drops until late in the year, the CIA had intended to smuggle them through East Pakistan and let them enter Nepal on foot. With Karachi's change of heart, however, they were stranded in Colorado. As it turned out, the agency saw a brief window of opportunity midway through summer. Despite his strong leanings toward India, Kennedy was unwilling to completely write off Pakistan. He had invited President Ayub Khan to Washington for a weeklong visit beginning 11 July. On the day of his arrival, the polished Pakistani leader and his daughter were the guests of honor at picturesque Mount Vernon. Seated between Kennedy and wife Jacqueline, Khan was feted during a spectacular dinner. Afterward, the two leaders took a stroll on the lawns of the estate. Taking advantage of the moment, Kennedy conveyed a personal plea from CIA Director Dulles to reopen the border. Caught up in the atmospherics, Ayub relented and agreed to let ten more Tibetans pass through his territory. Wasting little time, the CIA had the Tibetans through East Pakistan and into Mustang by August. There they found that eight companies had been formed in the Yara vicinity, each numbering less than 100 men. Half of this number were issued rifles from the first weapons drop; the remainder were designated as support personnel. Eight of the Hale graduates took charge as company commanders; the rest were to act as trainers and headquarters staff. Despite this promising start, problems quickly ensued. First, several of the Khampas were caught stealing animals and jewelry on the Chinese side of the border; this sent a chill through the local Mustang community, which was already beginning to have second thoughts about an armed Khampa presence in its midst. [42] Second, Baba Yeshi had not responded well to the CIA's plan for him to share authority with Sally. Outmaneuvering the Hale-trained officer, he made it clear that he was in complete control of both administration and field operations. Not that there were any field operations to command. Despite the influx of 400 weapons and couriered cash from Gyalo Thondup, allowing for the purchase of horses, the guerrillas stood fast inside Mustang. Not until September did seven guerrillas on horseback head northeast into Tibet. As the Chinese had declared the border area off-limits to herders, they found the region completely devoid of population. Moving over the course of four nights, they eventually came upon a small PLA outpost on the south bank of the Brahmaputra. While two tended to the horses, the remaining five guerrillas ambushed a Chinese patrol and killed several (estimates ranged between eight and thirteen) before racing back to Nepal. [43] Upon receiving a radio message with the results of Mustang's baptism by fire, the CIA was less than impressed. No photographs had been taken as proof of the supposed ambush, and no weapons were retrieved. And as this had been the first and only operation in the six months since the weapons drop, the guerrillas were not exactly setting a breakneck pace. Realizing that he had to do better for an encore, Baba Yeshi gathered his officers and outlined plans for a forty-man foray. Their target would be any vehicle plying the trans Tibet road running between Lhasa and Xinjiang. Completed in 1957 and of questionable quality, it was the only route connecting PLA border garrisons along a 2,400-kilometer stretch. Chosen to lead the incursion was thirty-five-year-old Rara, a Lithang native known by the call sign "Ross" during his stint at Hale. Since arriving via East Pakistan in August, he had assumed command of a company at Yara. For the road ambush, he assembled a composite unit by soliciting five men and five horses from each of the eight companies. They were all armed with a mix of Garands and carbines; in addition, Ross took a camera to document their foray. Heading north from Mustang on 21 October, the guerrillas traveled for three days before crossing the frozen Brahmaputra and coming upon the Xinjiang road. Keeping their horses concealed, the Tibetans deployed in an extended line among the boulders of an adjacent hill. There they sat in the biting cold for an entire day. Not until 1400 hours on 25 October did the sound ofa distant automobile break the silence. From the west, a lone olive-drab jeep came into view. Due to encroaching sand dunes, it could manage only a crawl along the clogged roadbed. Ross, who was at the closest end of the ambush, signaled the three guerrillas at his side to hold their fire until the vehicle was within range. [44] Taking aim with his carbine, Ross initiated the attack. Bullets ripped through the windshield, the driver's head snapped back, and the jeep veered to a halt on the shoulder. Two others in the front seat -- one male, one female -- slumped as their bodies were riddled by gunfire. Leaving the safety of the boulders, Ross exchanged his weapon for the camera. But as he moved forward to take photographs, gunfire began to pour from the rear of the jeep. Ross dove for cover while the three other guerrillas resumed their fusillade toward the back of the vehicle. After a minute, they converged on the now silent target and removed four dead Chinese. Putting his Hale training into practice, Ross wasted no time recovering three Chinese-made Type 56 carbines and a machine gun. He also took a large leather case from the front seat. The bodies were laid on the ground and stripped of uniforms, shoes, socks, and watches. After setting the jeep on fire, Ross blew a whistle as the signal for the rest of the guerrillas strung along the ridgeline to rendezvous near their horses. Three days later, the forty guerrillas were safely back in Mustang. Although photographs of the ambush were a bust (Ross had forgotten to take off the lens cap), the leather case looked promising. Baba Yeshi assigned two couriers to deliver the satchel to Lhamo Tsering in Darjeeling, who then personally carried it to Clay Cathey in Calcutta. When the case was opened, Cathey found himself staring at 1,600 pages of documents. Once Lhamo Tsering began preliminary translations of a sampling, the CIA officer determined that most of the material was classified up to top secret. "I sent a long cable listing some of the report titles," recalls Cathey. "A day later, headquarters sent a message saying it could be a gold mine." Once the satchel was back in Washington -- Cathey had strapped it in an adjacent seat aboard a Pan Am flight -- the CIA quickly realized that its initial assessment was correct. The male passenger in the front seat of the jeep, it turned out, had been a PLA regimental commander assigned to Tibet. Among the documents he was carrying were more than two dozen issues of a classified PLA journal entitled Bulletin of Activities. Intended for internal use among senior army cadre, the bulletins dealt frankly with problems plaguing the PLA. Some, for example, detailed food shortages and other economic problems, [45] others spoke of the lack of combat experience among junior officers, and still others reported on armed rebellions in the provinces. From the satchel documents, the CIA also learned that the People's Militia, a paramilitary unit that reportedly totaled more than 1 million, was in reality a paper organization. Yet another document discussed the intensity of the Sino-Soviet rivalry, and others listed communication codes. In the end, more than 100 CIA reports were generated from these papers. "This single haul became the basic staple of intelligence on the Chinese army," concluded Cathey. Better still, the Chinese did not know that the documents were missing, because the Tibetans had razed the jeep. Not until August 1963 did their existence become public knowledge after the CIA reached an agreement with scholars at Stanford University to help with the laborious translation. Although the source of the documents was not revealed, the agency threw the academics off the scent by hinting that they had been captured by the ROC navy from intercepted communist junks. [46] The CIA was ecstatic over its intelligence windfall, but Ambassador Galbraith did not share in the celebration. Persistent in his determination to put a stop to Mustang and further supply overflights, he fired off a series of scathing cables to Washington during November 1961. To add further punch, he made special note of Kennedy's 27 May letter to all American ambassadors charging each with responsibility for operations of the entire U.S. diplomatic mission. Implicit in this was his prerogative to cancel what he deemed an objectionable CIA operation. [47] Still, Galbraith could barely make headway. With the documents in the jeep satchel just beginning to be digested in Washington, the Tibet Task Force now had tangible proof of the operation's benefits. Armed with this, they secured final approval in early December for another pair of Hercules drops. For the guerrillas at Mustang, the omens were starting to look good.

|

|