|

THE CIA'S SECRET WAR IN TIBET -- REVOLUTION |

|

Chapter 17: Revolution The year had started on a most inauspicious note. On 10 January 1966, while in the Soviet city of Tashkent to negotiate an end to the Indo-Pakistan dispute in Kashmir, Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri suffered a fatal heart attack. As his body was flown home for cremation, party stalwarts in New Delhi looked to pick a second leader in as many years. Their choice eventually fell on Nehru's daughter, Indira Gandhi. Then in her mid-forties, she had made few political ripples of her own. Looking somewhat awkward and shy in public, Mrs. Gandhi had been elevated to power precisely because party seniors thought her pliable. President Johnson, for one, quickly found out otherwise. In March, Gandhi arrived in Washington on her first official foreign trip. Exuding both tact and charm, she earned Johnson's strong support for a major food aid package in exchange for market-oriented economic reforms. [1] With the Washington summit a success surpassing all expectations, Indo-U.S. relations got back some of the luster lost during the previous year's Kashmir crisis. Sensing an opportunity, the CIA on 22 April asked the 303 Committee to approve a major $18 million Tibetan paramilitary package. Part of this was earmarked to maintain the Mustang force for a three-year term. The package also included two C-130 aircraft as ELINT platforms to augment the lone ARC C-46 flying in this role, as well as funding for a 5,000-man increase in Establishment 22. [2] Most remarkable was the argument the CIA was using to justify its proposal. Moving beyond the lip service paid by Mullik in earlier years, the agency claimed that the Intelligence Bureau had drawn up plans in 1965 calling for the liberation of Tibet. Reading into this, the CIA suggested that India might be willing to commit Establishment 22 to a second front in the event circumstances in Vietnam sparked all-out hostilities between the United States and China. In making a linkage between Tibet and Vietnam, the CIA was being politically astute. Rather than justifying the Tibetan operation solely on its own merits, the agency was now trying to loosely fix it to the coattails of Indochina policy -- a topic that resonated at the top of the Johnson administration agenda. All this smacked of geopolitical fantasy. If Mullik, just a few months earlier, had balked at making airdrops to Mustang, it was a good bet that New Delhi would not willingly invite Beijing's wrath by sponsoring a Tibet front if the United States and China went to war over Vietnam. Even Ambassador Bowles, an ardent proponent of intelligence cooperation, quickly backpedaled on the Vietnam link. There was a "strong possibility" that India would be willing to commit its guerrilla forces against Tibet, he wrote in a secret cable on 28 April, but only if Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, or maybe Burma were attacked by China. [3] There was another problem with the CIA's April proposal. With few exceptions, the projects it sought to maintain had been proved ineffectual. Confirming as much was Bruce Walker, the former Camp Hale officer who had arrived that spring to replace John Gilhooley as the new CIA representative at the Special Center. In many respects, Walker was presiding over a funeral. Making a token appearance at Hauz Khas once a week, he had few remaining agents to oversee. "The radio teams were experiencing major resistance from the population inside Tibet," he recalls. "We were being pushed back to the border." [4] A good case in point was Team S. Agents Thad and Troy had started out well, identifying a sympathetic Tingri farmer and bivouacking at his house since the onset of snow the previous winter. Thad had gotten particularly close to his host's daughter; by early spring, her abdomen was starting to show the swell of pregnancy. This sparked rumors among suspicious neighbors, who reported the case to district officials. Alerted to the possible presence of an outsider, a Tibetan bureaucrat arrived that May to investigate. Quizzed about his daughter's mysterious suitor, the farmer folded. He brought Thad out from hiding, and they took the bureaucrat into their confidence and begged him to keep the matter a secret. Feigning compliance, the official bade them farewell -- only to return that same night with a PLA squad. Thad was captured immediately; Troy, concealed in a haystack, surrendered after being prodded with a bayonet. Giving the PLA the slip, the farmer managed to flee into the hills. Nearby was a cave inhabited by Team SI, which also consisted of two agents who had spent the winter near Tingri. Linking up, the three attempted to run south toward the Sikkimese border. Just short of the frontier, the trio encountered a PLA patrol and was felled in a hail of bullets. That left just one pair of agents still inside their homeland. Team F, consisting of Taylor and Jerome, had occupied yet another Tingri cave since the previous year. Even though they kept contact with the locals to a minimum, word of suspicious movement in the hills eventually came to the attention of the Chinese. On 2 November 1966, the PLA moved in for an arrest. The Tibetans held them at bay with their pistols until they ran out of ammunition; both were subsequently captured and placed in a Lhasa prison. As Team F's radio fell silent, the Special Center was at an impasse. After three seasons, the folly of attempting to infiltrate "black" radio teams (that is, teams without proper documentation or preparation to blend into the community) was evident. Earlier in the year, this growing realization had prompted the center to briefly flirt with a new kind of mission. Four agents were brought to the Indian capital from Joelikote and given instruction in the latest eavesdropping devices, with the intention of forming a special wiretap team. For practice, they climbed telephone poles around the Delhi cantonment area by night. [5] In the end, the wiretap agents never saw service. In late November, the Special Center put team infiltrations into Tibet on hold. Aside from a handful of Hale-trained Tibetans used for translation tasks at Oak Tree, as well as the radio teams already inside Nepal, Joelikote was closed, and the remaining agents reverted back to refugee status. "I was saddened and embarrassed," said Indian representative Rabi, "to have been party to those young men getting killed." *** The Special Center had also reached an impasse with its other main concern, the paramilitary force at Mustang. Despite the May 1965 arms drop, Baba Yeshi and his men had resisted all calls to relocate inside Tibet. Though frustrated, the CIA had continued financing the guerrillas for the remainder of that year. This funding flowed along a simple but effective underground railroad. Every month, a satchel of Indian rupees would be handed over by the agency representative at Hauz Khas. From there, two Tibetans and two Indian escorts would take the money to the Nepal frontier near Bhadwar. Meeting them were a pair of well-paid cyclo drivers also on the agency's payroll. They hid the cash under false seats and pedaled across the border, where they handed the money over to members of the Mustang force. The money would then go to Pokhara, where foodstuffs and textiles were purchased at the local market and shipped to the guerrillas via mule caravans. By the time of the 303 Committee's April 1966 meeting, the CIA was still prepared to continue such funding for another three years. In addition, the agency had not ruled out more arms drops in the future. The catch: Baba Yeshi had one final chance to move his men inside Tibet. Perhaps sensing that his financiers had run out of patience, the Mustang chieftain was jarred from complacency. Employing vintage theatrics, he gathered his headquarters staff in late spring and announced that he would personally lead a 400-man foray against the PLA. "We begged him not to do anything rash," said training officer Gen Gyurme. "Tears were flowing as he began his march out of Kaisang." [6] Traveling north to Tangya, the chieftain and thirty of his loyalists canvassed the nearby guerrilla camps for more participants. Another thirty signed on, including one company commander. Though far short of the promised 400, sixty armed Tibetans on horseback cut an impressive sight as they steered their mounts toward the border. Once the posse reached the frontier, however, the operation began to fall apart. A fifteen-man reconnaissance party was sent forward to locate a suitable ambush site, and the rest of the guerrillas argued for two days over whether Baba Yeshi should actually lead the raid across the border. After his men pleaded with him to reconsider, the chieftain finally relented in a flourish. Armed with information from the reconnaissance team, thirty-five Tibetans eventually remounted and galloped into Tibet. What ensued was a defining moment for the guerrilla force. Apparently alerted to the upcoming foray through their informant network, Chinese soldiers were waiting in ambush. Pinned in a valley, six Tibetans were shot dead, including the company commander. In addition, eight horses were killed and seven rifles lost. In its six years of existence, this was the greatest number of casualties suffered by the project. [7] As word of the failed foray filtered back to New Delhi, the Special Center finally acknowledged the limitations of Mustang. On the pretext of not provoking a PLA cross-border strike into Nepal, the guerrillas were "enjoined from offensive action which might invite Chinese retaliation." Any activity in their homeland, they were told, would be limited to passive intelligence collection. The guerrilla leadership, never really enthusiastic about conducting aggressive raids, offered no resistance to their restricted mandate. [8] *** By process of elimination, the only remaining Tibetan program with a modicum of promise was Establishment 22. Not only did this project have India's strong support, but it was the linchpin in the CIA's April pitch to the 303 Committee about a second front against China. [9] Even before the committee had time to respond, the agency was bringing in a new team of advisers to boost its level of assistance to Chakrata. Replacing Wayne Sanford in the U.S. embassy was Woodson "Woody" Johnson, a Colorado native who had served in a variety of intelligence and paramilitary assignments since joining the CIA in 1951. Working up-country alongside Establishment 22 was Zeke Zilaitis, the former Hale trainer with a taste for rockets, and Ken Seifarth, the airborne specialist on his encore tour with Brigadier Uban's guerrillas. [10] Tucker Gougelmann, the CIA's senior paramilitary adviser in India Boosting its representation a step further, the CIA that summer introduced forty-nine-year-old Tucker Gougelmann as the senior adviser for all paramilitary projects in India. A Columbia graduate, Gougelmann had gone from college to the Marine Corps back in 1940. A major by the summer of 1943, he was serving as intelligence officer for the marine airborne regiment before being seconded to a raider battalion during an amphibious landing at Vangunu Island in the Pacific. That transfer nearly sealed Gougelmann's fate. Just one day after landing, a sniper's bullet struck his upper left leg from the rear, ripping through nerve and bone. The wound was gangrenous by the time he was evacuated to a field clinic. Arriving in San Diego during late August, he was in and out of hospitals for the next three years. [11] By June 1946, the doctors had done all they could for Gougelmann's stricken limb. He retired from the marines that month with a permanent limp and a new wife from a moneyed family in Oakland. Her father, owner of a racetrack and a fruit-canning company, wanted his son-in-law to inherit part of the business. Gougelmann, however, had his heart set on overseas travel. Leaving his spouse behind, he joined the foreign relief organization CARE (Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe) as its Romanian representative. He would spend the next seventeen months in that country, the last being detained by Romania's newly empowered communist authorities. [12] Released from jail after an international outcry, Gougelmann returned home to find that his wife had had their marriage annulled in his absence. Repeating the same formula, he married again -- this time a New York girl -- before leaving her behind to work for an aid organization in China. Again he was chased out by advancing communists, and he came home to a second divorce. Given his passion for foreign adventure, Gougelmann joined the CIA in the fall of 1950. His first assignment was somewhat cloistered. Posted to a safe house on the outskirts of Munich, he served as an administrator for James Critchfield, then a case officer handling ex-Nazi spymaster Gehlen. "Tucker came with two pairs of highly polished paratrooper boots in a footlocker," recalled Critchfield, "and little else." [13] Though competent in the office, Gougelmann longed for the field. He transferred to Korea in the midst of the conflict on that peninsula and served as a maritime case officer and later as chief of operations at a training base that turned out road-watching teams. "His leg did not stop him," said fellow adviser Don Stephens. "He was still able to climb the rugged mountains with his students." [14] After returning from Korea with a refugee as his adopted daughter, Gougelmann served a stint as instructor at Camp Peary. Not until the summer of 1959 was he again overseas, this time posted as chief of station in Afghanistan. The assignment hardly suited the gruff former major. Arriving with his infamous footlocker and ready to do battle, he was instead channeled toward the cocktail circuit to keep tabs on the Soviets in a more classic espionage duel. "Tucker was devoid of any social graces," said fellow Afghan officer Alan Wolfe, "and ill at ease in such diplomatic settings." [15] By the time his Kabul tour finished in the summer of 1962, Gougelmann was yearning for a return to paramilitary action. The Vietnam conflict was fast escalating at that time, and a choice slot had opened up in the coastal city of Da Nang. To put pressure on the communist government in Hanoi, the CIA was mandated to begin a maritime raiding campaign using an exotic mix of Swift boats, Norwegian mercenary skippers, and Vietnamese frogmen. For the next three years, Gougelmann led this effort, often with more flair than success. [16] Gougelmann remained in Vietnam for another year, and it was then that he made his mark. While advising the South Vietnamese Special Branch -- a police-cum-intelligence organization focused on the communist infrastructure -- he organized a string of provincial interrogation centers. Despite his unpolished demeanor and proclivity for salty language, Gougelmann displayed a sharp, calculating mind in this role. "He could walk to an empty blackboard," said one fellow officer, "and start diagramming the local communist party ... from memory." [17] By the time Gougelmann got his India assignment in mid-1966, he had a full plate. Part of his time was devoted to managing the mountaineering expeditions aimed at placing a nuclear-powered sensor atop the Nanda Devi summit. [18] Even more of Gougelmann's time was spent arranging assistance for the guerrillas at Chakrata. The Indians were eager to double the number of Tibetans at Establishment 22 and were even calling for the recruitment of Gurkhas into the unit. Reflecting bureaucratic creep, Director General of Security Mullik had come up with a new, more formal name for the outfit -- the Special Frontier Force, or SFF -- and had given Uban an office in New Delhi. The SFF had matured considerably since its humble start. One hundred twenty-two guerrillas made up each of its companies, with five or six companies grouped into battalions commanded by Tibetan political leaders. Though expanding the size of the SFF would be easy in one sense -- with thousands of idle refugees eager for meaningful employment -- there were problems. Most of the training was being handled by Uban's seasoned cadre; aside from perfunctory oversight provided by Seifarth and Zilaitis, the CIA was relegated to funding and bringing in the occasional instructor from Camp Peary for brief specialist courses. One such instructor, Henry "Hank" Booth, was dispatched in 1967 to offer a class in sniping. The six-week program went well, with the Tibetans proving themselves able shots with the 1903 Springfield rifle. For graduation, Uban held a small ceremony, during which Booth awarded his students a copy of the 1944 U.S. Army field manual for snipers. What came next was a telling indictment of the relationship between the Tibetans and their Indian hosts. Late that same evening, a fellow CIA officer took Booth to a hill overlooking the SFF cantonment. Below were lights burning bright at five separate camps. The Tibetans were in the process of translating the field manual into Tibetan, with each camp doing a section of the manual. Multiple copies were being made -- including hand-drawn reproductions of the diagrams -- and exchanged by runners. By sunrise, as Booth departed for New Delhi, each unit had a complete copy of the book, and the Indians moved in to confiscate the manual. [19] Hank Booth with the top SFF marksmen at his sniper course, December 1967. Not helping the relationship between the Indians and the Tibetans was the decision to add Gurkhas to their ranks. The Indians saw this as a means of expanding the mandate and abilities of the force beyond things Tibetan. The Tibetans, however, bristled at the ethnic dilution of their unit. Brigadier Uban recognized the delicacy of juggling two different cultures. "The Tibetans were more ferocious," he reflected, "but the Gurkhas were more disciplined." [20] Wayne Sanford, who had returned to India for another CIA tour in New Delhi, was less generous in his assessment of the Gurkhas. "We would kill off their leaders during training exercises," he said. "The Tibetans were natural fighters and would move the next best guy into the leader's slot and keep on operating; the Gurkhas were clueless without leadership." [21] To keep peace within the force, a cap was set at no more than 100 Gurkhas. In addition, the two ethnicities would not be mixed; the Gurkhas would be segregated into their own "G Group" at Chakrata. Though given the same paramilitary training as in the previous SFF cycles, G Group was relegated primarily to base security and administration. [22] The Tibetan majority, meanwhile, was being rotated along the Ladakh and NEFA border in company-size elements. Several ARC air bases were established specifically to support these SFF operations. In the northeast, the ARC staged from a primitive airstrip at Doomdoomah in Assam. For northwestern operations and airborne training, it used a larger air base built at Sarsawa, 132 kilometers south of Chakrata. [23] To feed the remote SFF outposts along the border, the CIA had enlisted the Kellogg Company to help develop a special tsampa loaded with vitamins and other nutrients. Not only did this appeal to Tibetan tastes, but it allowed for healthy daily rations to be concentrated in small packages that could be airdropped from ARC planes. [24] Not all the SFF missions were within India's frontier. Back in 1964, an Establishment 22 team had staged a brief but deadly foray from Nepal toward Tingri. In 1966, the force inherited the wiretap mandate originally conjured for the special team selected from Joelikote. There was good reason to target China's phones. Nearly all the communications between China and Tibet used over-ground lines supported by concrete or improvised wooden poles. The CIA, moreover, had already started a successful wiretap program in southern China using agent teams staging from Laos. Placing the taps posed serious challenges. The lines paralleled the roads built across Tibet, most of which were a fair hike from the border. Once a tap was placed at the top of a pole, a wire needed to run to a concealed cassette recorder. Because the recording time on each cassette was limited, an agent had to remain nearby to change tapes and then bring them back to India for CIA analysis. The SFF proved up to the task. In a project code-named GEM1NI, it began infiltrating from NEFA with recording gear during mid-1966. To supply the guerrillas while they filled the tapes, an ARC C-46 was dispatched to an airfield near Siliguri. Taking off during predawn hours, the plane would overfly the Sikkimese corridor and be at the team's position by daybreak. Flying with the rear door open, the kickers briefly took leave of their oxygen bottles and shawls to push the cargo into the slipstream. On the way home, they would hang a bag of soft drinks out the door in order to have chilled refreshments by the time they returned to base. [25] The results of GEMINI were mixed. Although the SFF guerrillas were able to ex filtrate without loss of life, the project was put on hold near year's end after a Calcutta newspaper reported the mysterious flights over Sikkim. "We got miles of tapes," recalled New Delhi officer Angus Thuermer, "but much of it was useless, like Chinese talking about their families back home." Deputy chief of station Bill Grimsley was more upbeat in his assessment: "One never knows where the intelligence will lead in these matters." [26] The 303 Committee apparently agreed. On 25 November, after repeated failed attempts during the first three quarters of the year, the CIA put a small portion of its $18 million Tibet package before the committee for endorsement. It totaled just $650,000, most of it going to pay for Mustang. This time, the policy makers offered their approval for the paramilitary program to proceed. *** The Chinese, however, were not taking notice. In mid-1966, Beijing had reached a turning point. Its Great Leap campaign toward rapid industrialization and full-scale communism, launched by Chairman Mao with much fanfare late the previous decade, had been such a failure that its third Five-Year Plan had to be delayed three years. The country had also suffered a series of foreign policy setbacks, including the annihilation of the Communist Party in Indonesia -- which included some of China's closest political allies in Asia -- allowing an abortive September 1965 coup. And with Mao both aging and ailing, there were questions about who would succeed him. Reacting against all this, Mao formally proclaimed a Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in August 1966. In what was part ideological purge, part power struggle, part policy dispute, Mao steered the nation toward a destructive campaign of sophomoric Marxism and paranoid suspicion, ostensibly to "cleanse its rotten core." Leading the charge was disaffected youth gathered into a mass organization dubbed the Red Guard. These teenagers joined with the army and attacked allegedly anti-Mao elements in the Communist Party, then hit the party machine as a whole. Three months before the Cultural Revolution was proclaimed, Red Guards had already started arriving in Lhasa from Beijing. As the revolution's goal was to wipe out divergent habits and cultures in order to make all of Chinese society conform to a communist ideal, minorities were a prime target. Tibetans, predictably, suffered tremendously. Thousands were jailed by marauding Red Guard gangs. Monasteries were emptied, monks publicly humiliated, scriptures burned, and priceless art treasures destroyed. Belatedly realizing that he had lost control, Mao in January 1967 attempted to soften his rhetoric and asked the military to intervene. This had little effect in Tibet, where the empowered Red Guard took on the army in street battles across Lhasa through the spring and summer. *** As China descended into this orgy of violence, India watched with understandable concern. With nobody in clear control of Beijing (Mao was prone to prolonged absences from the capital, apparently for fear of his life), the Chinese were more dangerous neighbors than ever. Making matters worse, they had successfully tested a nuclear-tipped medium-range ballistic missile in October 1966. In years past, such conditions might have made India's covert Tibetan assets appear all the more relevant as both a border force and a potential tool to exploit China's turmoil. By the spring of 1967, however, New Delhi had irreversibly soured toward most of its joint paramilitary projects. After all, the black radio teams inside Tibet had already been canceled, and the Mustang force hardly inspired confidence. The Indians were also nervous about media revelations concerning the CIA. In March 1967, Ramparts, a liberal U.S. magazine critical of the government, published an expose on covert CIA support for various private organizations, including the Asia Foundation (originally known as the Committee for a Free Asia). Because numerous U.S. educational and voluntary groups were active in India, this sparked an anti-CIA furor in the Indian parliament. [27] Never openly embraced, the CIA now had few advocates on the subcontinent. Mullik, who had chaperoned the Tibet projects since the beginning of Indian involvement, had already given up his seat as director general of security in mid-1966. His replacement, Balbir Singh, had an independent and forceful personality but only limited clout with the prime minister. For her part, Mrs. Gandhi showed little appreciation for the agency or its assistance. "We became a tolerated annoyance," summed up Woody Johnson. [28] If any tears were being shed at the CIA, they were of the crocodile variety. Back in June 1966, the director's slot had been filled by Richard Helms. Coming to the office with extensive experience managing clandestine intelligence collection, Helms was known to be highly skeptical of covert action like that attempted in Tibet. However, he was being counseled otherwise by Des FitzGerald, his deputy for operations and longtime proponent of activism in Tibet. Unfortunately, FitzGerald dropped dead while playing tennis in July 1967. "When Des died," said Near East chief James Critchfield, "the 'oomph' for the program quickly dissipated." [29] Even before FitzGerald's death, the agency had taken measured steps to disengage itself from Tibet. In the wake of the March Ramparts revelations, President Johnson had approved a special committee headed by Undersecretary of State Nicholas Katzenbach to study U.S. relationships with private organizations. Katzenbach's findings, released later that month, recommended against covert assistance to any American educational or private voluntary organization. [30] Following this finding, the CIA terminated funding for the third cycle of eight Tibetans undergoing training at Cornell University. They were repatriated to Dharamsala in July, and no further students were accepted. Though the agency contemplated a continuation of the program on a smaller scale at a foreign university, this never came to fruition. [31] Other changes came in rapid succession. In Washington, the Tibet desk, which had been under the Far East Division's China Branch ever since its establishment in 1956, was transferred to the Near East Division. John Rickard, one of four brothers born to missionary parents in Burma (three of whom went to work for the CIA) , headed the desk during this period and changed his divisional affiliation to reflect the shift. More than just semantics, the change underscored the fact that the remaining Tibetan paramilitary assets, with rare exception, would probably not be leaving Indian soil. Apart from a single representative at the Special Center, the Far East Division had been completely excised from the Tibet program. [32] The CIA also reduced its links to the ARC. Although attrition was starting to take a toll on the planes delivered during 1963 and 1964 -- the latest casualty, a Twin Helio, crashed in 1967 -- no replacements were budgeted. More telling, after the CIA removed the C-130 from the limited proposal passed by the 303 Committee the previous November, the Indians opted in 1967 to add the Soviet An-12 transport as the new centerpiece for its ARC fleet. [33] For the Tibetans, the biggest blow took place in the spring of 1967. Ever since arriving on Indian soil, the CIA had secretly channeled a stipend to the Dalai Lama and his entourage. Totaling $180,000 per fiscal year, the money was appreciated but not critical. Most of it was collected in the Charitable Trust of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, which in turn was used for investments, donations, and relief work. To their credit, the Tibetans had worked hard to wean themselves off such handouts. "Financially underpinning the Dalai Lama's refugee programs was no longer warranted, " said Grimsley. [34] Gyalo did not see it that way. Sullen, he made the assumption that all money would soon be drying up. He was not wrong.

|

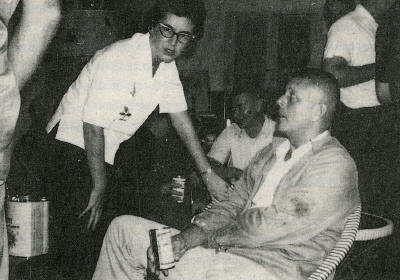

|