CHAPTER II.

HABITS OF WORMS—continued.

Manner in which worms seize

objects—Their power of suction—The instinct of plugging up the mouths of

their burrows—Stones piled over the burrows—The advantages thus

gained—Intelligence shown by worms in their manner of plugging up their

burrows—Various kinds of leaves and other objects thus used—Triangles of

paper—Summary of reasons for believing that worms exhibit some

intelligence—Means by which they excavate their burrows, by pushing away

the earth and swallowing it—Earth also swallowed for the nutritious

matter which it contains—Depth to which worms burrow, and the

construction of their burrows—Burrows lined with castings, and in the

upper part with leaves—The lowest part paved with little stones or

seeds—Manner in which the castings are ejected—The collapse of old

burrows—Distribution of worms—Tower-like castings in Bengal—Gigantic

castings on the Nilgiri Mountains—Castings ejected in all countries.

In the pots in which worms were kept, leaves were

pinned down to the soil, and at night the manner in which they were

seized could be observed. The worms always endeavoured to drag the

leaves towards their burrows; and they tore or sucked off small

fragments, whenever the leaves were sufficiently tender. They generally

seized the thin edge of a leaf with their mouths, between the projecting

upper and lower lip; the thick and strong pharynx being at the same

time, as Perrier remarks, pushed forward within their bodies, so as to

afford a point of resistance for the upper lip. In the case of broad

flat objects they acted in a wholly different manner. The pointed

anterior extremity of the body, after being brought into contact with an

object of this kind, was drawn within the adjoining rings, so that it

appeared truncated and became as thick as the rest of the body. This

part could then be seen to swell a little; and this, I believe, is due

to the pharynx being pushed a little forwards. Then by a slight

withdrawal of the pharynx or by its expansion, a vacuum was produced

beneath the truncated slimy end of the body whilst in contact with the

object; and by this means the two adhered firmly together. [1] That

under these circumstances a vacuum was produced was plainly seen on one

occasion, when a large worm lying beneath a flaccid cabbage leaf tried

to drag it away; for the surface of the leaf directly over the end of

the worms body became deeply pitted. On another occasion a worm suddenly

lost its hold on a flat leaf; and the anterior end of the body was

momentarily seen to be cup-formed. Worms can attach themselves to an

object beneath water in the same manner; and I saw one thus dragging

away a submerged slice of an onion-bulb.

The edges of fresh or nearly fresh leaves affixed to

the ground were often nibbled by the worms; and sometimes the epidermis

and all the parenchyma on one side was gnawed completely away over a

considerable space; the epidermis alone on the opposite side being left

quite clean. The veins were never touched, and leaves were thus

sometimes partly converted into skeletons. As worms have no teeth and as

their mouths consist of very soft tissue, it may be presumed that they

consume by means of suction the edges and the parenchyma of fresh

leaves, after they have been softened by the digestive fluid. They

cannot attack such strong leaves as those of sea-kale or large and thick

leaves of ivy; though one of the latter after it had become rotten was

reduced in parts to the state of a skeleton.

Worms seize leaves and other objects, not only to

serve as food, but for plugging up the mouths of their burrows; and this

is one of their strongest instincts. Leaves and petioles of many kinds,

some flower-peduncles, often decayed twigs of trees, bits of paper,

feathers, tufts of wool and horse-hairs are dragged into their burrows

for this purpose. I have seen as many as seventeen petioles of a

Clematis projecting from the mouth of one burrow, and ten from the mouth

of another. Some of these objects, such as the petioles just named,

feathers, &c., are never gnawed by worms. In a gravel walk in my garden

I found many hundred leaves of a pine-tree (P. austriaca or

nigricans) drawn by their bases into burrows. The surfaces by which

these leaves are articulated to the branches are shaped in as peculiar a

manner as is the joint between the leg-bones of a quadruped; and if

these surfaces had been in the least gnawed, the fact would have been

immediately visible, but there was no trace of gnawing. Of ordinary

dicotyledonous leaves, all those which are dragged into burrows are not

gnawed. I have seen as many as nine leaves of the lime-tree drawn into

the same burrow, and not nearly all of them had been gnawed; but such

leaves may serve as a store for future consumption. Where fallen leaves

are abundant, many more are sometimes collected over the mouth of a

burrow than can be used, so that a small pile of unused leaves is left

like a roof over those which have been partly dragged in.

A leaf in being dragged a little way into a

cylindrical burrow is necessarily much folded or crumpled. When another

leaf is drawn in, this is done exteriorly to the first one, and so on

with the succeeding leaves; and finally all become closely folded and

pressed together. Sometimes the worm enlarges the mouth of its burrow,

or makes a fresh one close by, so as to draw in a still larger number of

leaves. They often or generally fill up the interstices between the

drawn-in leaves with moist viscid earth ejected from their bodies; and

thus the mouths of the burrows are securely plugged. Hundreds of such

plugged burrows may be seen in many places, especially during the

autumnal and early winter months. But, as will hereafter be shown,

leaves are dragged into the burrows not only for plugging them up and

for food, but for the sake of lining the upper part or mouth.

When worms cannot obtain leaves, petioles, sticks,

&c., with which to plug up the mouths of their burrows, they often

protect them by little heaps of stones; and such heaps of smooth rounded

pebbles may frequently be seen on gravel-walks. Here there can be no

question about food. A lady, who was interested in the habits of worms,

removed the little heaps of stones from the mouths of several burrows

and cleared the surface of the ground for some inches all round. She

went out on the following night with a lantern, and saw the worms with

their tails fixed in their burrows, dragging the stones inwards by the

aid of their mouths, no doubt by suction. "After two nights some of the

holes had 8 or 9 small stones over them; after four nights one had about

30, and another 34 stones." [2] One stone which had been dragged over

the gravel-walk to the mouth of a burrow weighed two ounces; and this

proves how strong worms are. But they show greater strength in sometimes

displacing stones in a well-trodden gravel-walk; that they do so, may be

inferred from the cavities left by the displaced stones being exactly

filled by those lying over the mouths of adjoining burrows, as I have

myself observed.

Work of this kind is usually performed during the

night; but I have occasionally known objects to be drawn into the

burrows during the day. What advantage the worms derive from plugging up

the mouths of their burrows with leaves, &c., or from piling stones over

them, is doubtful. They do not act in this manner at the times when they

eject much earth from their burrows; for their castings then serve to

cover the mouth. When gardeners wish to kill worms on a lawn, it is

necessary first to brush or rake away the castings from the surface, in

order that the lime-water may enter the burrows. [3] It might be

inferred from this fact that the mouths are plugged up with leaves, &c.,

to prevent the entrance of water during heavy rain; but it may be urged

against this view that a few, loose, well-rounded stones are ill-adapted

to keep out water. I have moreover seen many burrows in the

perpendicularly cut turf-edgings to gravel-walks, into which water could

hardly flow, as well plugged as burrows on a level surface. Can the

plugs or piles of stones aid in concealing the burrows from scolopenders,

which, according to Hoffmeister, [4] are the bitterest enemies of worms?

Or may not worms when thus protected be able to remain with safety with

their heads close to the mouths of their burrows, which we know that

they like to do, but which costs so many of them their lives? Or may not

the plugs check the free ingress, of the lowest stratum of air, when

chilled by radiation at night, from the surrounding ground and herbage.

I am inclined to believe in this latter view; firstly, because when

worms were kept in pots in a room with a fire, in which case cold air

could not enter the burrows, they plugged them up in a slovenly manner;

and secondarily, because they often coat the upper part of their burrows

with leaves, apparently to prevent their bodies from coming into close

contact with the cold damp earth. But the plugging-up process may

perhaps serve for all the above purposes.

Whatever the motive may be, it appears that worms much

dislike leaving the mouths of their burrows open. Nevertheless they will

reopen them at night, whether or not they can afterwards close them.

Numerous open burrows may be seen on recently-dug ground, for in this

case the worms eject their castings in cavities left in the ground, or

in the old burrows, instead of piling them over the mouths of their

burrows, and they cannot collect objects on the surface by which the

mouths might be protected. So again on a recently disinterred pavement

of a Roman villa at Abinger (hereafter to be described) the worms

pertinaciously opened their burrows almost every night, when these had

been closed by being trampled on, although they were rarely able to find

a few minute stones wherewith to protect them.

Intelligence shown by worms in their manner of

plugging up their burrows.—If a man had to

plug up a small cylindrical hole, with such objects as leaves, petioles

or twigs, he would drag or push them in by their pointed ends; but if

these objects were very thin relatively to the size of the hole, he

would probably insert some by their thicker or broader ends. The guide

in his case would be intelligence. It seemed therefore worth while to

observe carefully how worms dragged leaves into their burrows; whether

by their tips or bases or middle parts. It seemed more especially

desirable to do this in the case of plants not natives to our country;

for although the habit of dragging leaves into their burrows is

undoubtedly instinctive with worms, yet instinct could not tell them how

to act in the case of leaves about which their progenitors knew nothing.

If, moreover, worms acted solely through instinct or an unvarying

inherited impulse, they would draw all kinds of leaves into their

burrows in the same manner. If they have no such definite instinct, we

might expect that chance would determine whether the tip, base or middle

was seized. If both these alternatives are excluded, intelligence alone

is left; unless the worm in each case first tries many different

methods, and follows that alone which proves possible or the most easy;

but to act in this manner and to try different methods makes a near

approach to intelligence.

In the first place 227 withered leaves of various

kinds, mostly of English plants, were pulled out of worm-burrows in

several places. Of these, 181 had been drawn into the burrows by or near

their tips, so that the foot-stalk projected nearly upright from the

mouth of the burrow; 20 had been drawn in by their bases, and in this

case the tips projected from the burrows; and 26 had been seized near

the middle, so that these had been drawn in transversely and were much

crumpled. Therefore 80 per cent. (always using the nearest whole number)

had been drawn in by the tip, 9 per cent. by the base or footstalk, and

11 per cent. transversely or by the middle. This alone is almost

sufficient to show that chance does not determine the manner in which

leaves are dragged into the burrows.

Of the above 227 leaves, 70 consisted of the fallen

leaves of the common lime-tree, which is almost certainly not a native

of England. These leaves are much acuminated towards the tip, and are

very broad at the base with a well-developed foot-stalk. They are thin

and quite flexible when half-withered. Of the 70, 79 per cent. had been

drawn in by or near the tip; 4 per cent. by or near the base; and 17 per

cent. transversely or by the middle. These proportions agree very

closely, as far as the tip is concerned, with those before given. But

the percentage drawn in by the base is smaller, which may be attributed

to the breadth of the basal part of the blade. We here, also, see that

the presence of a foot-stalk, which it might have been expected would

have tempted the worms as a convenient handle, has little or no

influence in determining the manner in which lime leaves are dragged

into the burrows.

The considerable proportion, viz., 17 per cent., drawn

in more or less transversely depends no doubt on the flexibility of

these half-decayed leaves. The fact of so many having been drawn in by

the middle, and of some few having been drawn in by the base, renders it

improbable that the worms first tried to draw in most of the leaves by

one or both of these methods, and that they afterwards drew in 79 per

cent. by their tips; for it is clear that they would not have failed in

drawing them in by the base or middle.

The leaves of a foreign plant were next searched for,

the blades of which were not more pointed towards the apex than towards

the base. This proved to be the case with those of a laburnum (a hybrid

between Cytisus alpinus and laburnum) for on doubling

the terminal over the basal half, they generally fitted exactly; and

when there was any difference, the basal half was a little the narrower.

It might, therefore, have been expected that an almost equal number of

these leaves would have been drawn in by the tip and base, or a slight

excess in favour of the latter. But of 73 leaves (not included in the

first lot of 227) pulled out of worm-burrows, 63 per cent. had been

drawn in by the tip; 27 per cent. by the base, and 10 per cent.

transversely. We here see that a far larger proportion, viz., 27 per

cent. were drawn in by the base than in the case of lime leaves, the

blades of which are very broad at the base, and of which only 4 per

cent. had thus been drawn in. We may perhaps account for the fact of a

still larger proportion of the laburnum leaves not having been drawn in

by the base, by worms having acquired the habit of generally drawing in

leaves by their tips and thus avoiding the foot-stalk. For the basal

margin of the blade in many kinds of leaves forms a large angle with the

foot-stalk; and if such a leaf were drawn in by the foot-stalk, the

basal margin would come abruptly into contact with the ground on each

side of the burrow, and would render the drawing in of the leaf very

difficult.

Nevertheless worms break through their habit of

avoiding the footstalk, if this part offers them the most convenient

means for drawing leaves into their burrows. The leaves of the endless

hybridised varieties of the Rhododendron vary much in shape; some are

narrowest towards the base and others towards the apex. After they have

fallen off, the blade on each side of the midrib often becomes curled up

while drying, sometimes along the whole length, sometimes chiefly at the

base, sometimes towards the apex. Out of 28 fallen leaves on one bed of

peat in my garden, no less than 23 were narrower in the basal quarter

than in the terminal quarter of their length; and this narrowness was

chiefly due to the curling in of the margins. Out of 36 fallen leaves on

another bed, in which different varieties of the Rhododendron grew, only

17 were narrower towards the base than towards the apex. My son William,

who first called my attention to this case, picked up 237 fallen leaves

in his garden (where the Rhododendron grows in the natural soil) and of

these 65 per cent. could have been drawn by worms into their burrows

more easily by the base or foot-stalk than by the tip; and this was

partly due to the shape of the leaf and in a less degree to the curling

in of the margins: 27 percent. could have been drawn in more easily by

the tip than by the base: and 8 per cent. with about equal ease by

either end. The shape of a fallen leaf ought to be judged of before one

end has been drawn into a burrow, for after this has happened, the free

end, whether it be the base or apex, will dry more quickly than the end

embedded in the damp ground; and the exposed margins of the free end

will consequently tend to become more curled inwards than they were when

the leaf was first seized by the worm. My son found 91 leaves which had

been dragged by worms into their burrows, though not to a great depth;

of these 66 per cent. had been drawn in by the base or foot-stalk; and

34 per cent. by the tip. In this case, therefore, the worms judged with

a considerable degree of correctness how best to draw the withered

leaves of this foreign plant into their burrows; notwithstanding that

they had to depart from their usual habit of avoiding the foot-stalk.

On the gravel-walks in my garden a very large number

of leaves of three species of Pinus (P. austriaca, nigricans

and sylvestris) are regularly drawn into the mouths of

worm-burrows. These leaves consist of two needles, which are of

considerable length in the two first and short in the last named

species, and are united to a common base; and it is by this part that

they are almost invariably drawn into the burrows. I have seen only two

or at most three exceptions to this rule with worms in a state of

nature. As the sharply pointed needles diverge a little, and as several

leaves are drawn into the same burrow, each tuft forms a perfect

chevaux de frise. On two occasions many of these tufts were pulled

up in the evening, but by the following morning fresh leaves had been

pulled in, and the burrows were again well protected. These leaves could

not be dragged into the burrows to any depth, except by their bases, as

a worm cannot seize hold of the two needles at the same time, and if one

alone were seized by the apex, the other would be pressed against the

ground and would resist the entry of the seized one. This was manifest

in the above mentioned two or three exceptional cases. In order,

therefore that worms should do their work well, they must drag

pine-leaves into their burrows by their bases, where the two needles are

conjoined. But how they are guided in this work is a perplexing

question.

This difficulty led my son Francis and myself to

observe worms in confinement during several nights by the aid of a dim

light, while they dragged the leaves of the above named pines into their

burrows. They moved the anterior extremities of their bodies about the

leaves, and on several occasions when they touched the sharp end of a

needle they withdrew suddenly as if pricked. But I doubt whether they

were hurt, for they are indifferent to very sharp objects, and will

swallow even rose-thorns and small splinters of glass. It may also be

doubted, whether the sharp ends of the needles serve to tell them that

this is the wrong end to seize; for the points were cut off many leaves

for a length of about one inch, and fifty-seven of them thus treated

were drawn into the burrows by their bases, and not one by the cut-off

ends. The worms in confinement often seized the needles near the middle

and drew them towards the mouths of their burrows; and one worm tried in

a senseless manner to drag them into the burrow by bending them. They

sometimes collected many more leaves over the mouths of their burrows

(as in the case formerly mentioned of lime-leaves) than could enter

them. On other occasions, however, they behaved very differently; for as

soon as they touched the base of a pine-leaf, this was seized, being

sometimes completely engulfed in their mouths, or a point very near the

base was seized, and the leaf was then quickly dragged or rather jerked

into their burrows. It appeared both to my son and myself as if the

worms instantly perceived as soon as they had seized a leaf in the

proper manner. Nine such cases were observed, but in one of them the

worm failed to drag the leaf into its burrow, as it was entangled by

other leaves lying near. In another case a leaf stood nearly upright

with the points of the needles partly inserted into a burrow, but how

placed there was not seen; and then the worm reared itself up and seized

the base, which was dragged into the mouth of the burrow by bowing the

whole leaf. On the other hand, after a worm had seized the base of a

leaf, this was on two occasions relinquished from some unknown motive.

As already remarked, the habit of plugging up the

mouths of the burrows with various objects, is no doubt instinctive in

worms; and a very young one, born in one of my pots, dragged for some

little distance a Scotchfir leaf, one needle of which was as long and

almost as thick as its own body. No species of pine is endemic in this

part of England, it is therefore incredible that the proper manner of

dragging pine-leaves into the burrows can be instinctive with our worms.

But as the worms on which the above observations were made, were dug up

beneath or near some pines, which had been planted there about forty

years, it was desirable to prove that their actions were not

instinctive. Accordingly, pine-leaves were scattered on the ground in

places far removed from any pine-tree, and 90 of them were drawn into

the burrows by their bases. Only two were drawn in by the tips of the

needles, and these were not real exceptions, as one was drawn in for a

very short distance, and the two needles of the other cohered. Other

pine-leaves were given to worms kept in pots in a warm room, and here

the result was different; for out of 42 leaves drawn into the burrows,

no less than 16 were drawn in by the tips of the needles. These worms,

however, worked in a careless or slovenly manner; for the leaves were

often drawn in to only a small depth; sometimes they were merely heaped

over the mouths of the burrows, and sometimes none were drawn in. I

believe that this carelessness may be accounted for by the air of the

room being warm, and the worms consequently not being anxious to plug up

their holes effectually. Pots tenanted by worms and covered with a net

which allowed the entrance of cold air, were left out of doors for

several nights, and now 72 leaves were all properly drawn in by their

bases.

It might perhaps be inferred from the facts as yet

given, that worms somehow gain a general notion of the shape or

structure of pine leaves, and perceive that it is necessary for them to

seize the base where the two needles are conjoined. But the following

cases make this more than doubtful. The tips of a large number of

needles of P. austriaca were cemented together with shell-lac

dissolved in alcohol, and were kept for some days, until, as I believe,

all odour or taste had been lost; and they were then scattered on the

ground where no pine-trees grew, near burrows from which the plugging

had been removed. Such leaves could have been drawn into the burrows

with equal ease by either end; and judging from analogy and more

especially from the case presently to be given of the petioles of

Clematis montana, I expected that the apex would have been

preferred. But the result was that out of 121 leaves with the tips

cemented, which were drawn into burrows, 108 were drawn in by their

bases, and only 13 by their tips. Thinking that the worms might possibly

perceive and dislike the smell or taste of the shell-lac, though this

was very improbable, especially after the leaves had been left out

during several nights, the tips of the needles of many leaves were tied

together with fine thread. Of leaves thus treated 150 were drawn into

burrows—123 by the base and 27 by the tied tips; so that between four

and five times as many were drawn in by the base as by the tip. It is

possible that the short cut-off ends of the thread with which they were

tied, may have tempted the worms to drag in a larger proportional number

by the tips than when cement was used. Of the leaves with tied and

cemented tips taken together (271 in number) 85 per cent. were drawn in

by the base and 15 per cent. by the tips. We may therefore infer that it

is not the divergence of the two needles which leads worms in a state of

nature almost invariably to drag pine-leaves into their burrows by the

base. Nor can it be the sharpness of the points of the needles which

determines them; for, as we have seen, many leaves with the points cut

off were drawn in by their bases. We are thus led to conclude, that with

pine-leaves there must be something attractive to worms in the base,

notwithstanding that few ordinary leaves are drawn in by the base or

footstalk.

Petioles.—We will now

turn to the petioles or foot-stalks of compound leaves, after the

leaflets have fallen off. Those from Clematis montana, which

grew over a verandah, were dragged early in January in large numbers

into the burrows on an adjoining gravel-walk, lawn, and flower-bed.

These petioles vary from 2½ to 4½ inches in length, are rigid and of

nearly uniform thickness, except close to the base where they thicken

rather abruptly, being here about twice as thick as in any other part.

The apex is somewhat pointed, but soon withers and is then easily broken

off. Of these petioles, 314 were pulled out of burrows in the above

specified sites; and it was found that 76 per cent. had been drawn in by

their tips, and 24 per cent. by their bases; so that those drawn in by

the tip were a little more than thrice as many as those drawn in by the

base. Some of those extracted from the well-beaten gravel-walk were kept

separate from the others; and of these (59 in number) nearly five times

as many had been drawn in by the tip as by the base; whereas of those

extracted from the lawn and flower-bed, where from the soil yielding

more easily, less care would be necessary in plugging up the burrows,

the proportion of those drawn in by the tip (130) to those drawn in by

the base (48) was rather less than three to one. That these petioles had

been dragged into the burrows for plugging them up, and not for food,

was manifest, as neither end, as far as I could see, had been gnawed. As

several petioles are used to plug up the same burrow, in one case as

many as 10, and in another case as many as 15, the worms may perhaps at

first draw in a few by the thicker end so as to save labour; but

afterwards a large majority are drawn in by the pointed end, in order to

plug up the hole securely.

The fallen petioles of our native ash-tree were next

observed, and the rule with most objects, viz., that a large majority

are dragged into the burrows by the more pointed end, had not here been

followed; and this fact much surprised me at first. These petioles vary

in length from 5 to 8½ inches; they are thick and fleshy towards the

base, whence they taper gently towards the apex, which is a little

enlarged and truncated where the terminal leaflet had been originally

attached. Under some ash-trees growing in a grass-field, 229 petioles

were pulled out of worm burrows early in January, and of these 51.5 per

cent. had been drawn in by the base, and 48.5 percent. by the apex. This

anomaly was however readily explained as soon as the thick basal part

was examined; for in 78 out of 103 petioles, this part had been gnawed

by worms, just above the horse-shoe shaped articulation. In most cases

there could be no mistake about the gnawing; for ungnawed petioles which

were examined after being exposed to the weather for eight additional

weeks had not become more disintegrated or decayed near the base than

elsewhere. It is thus evident that the thick basal end of the petiole is

drawn in not solely for the sake of plugging up the mouths of the

burrows, but as food. Even the narrow truncated tips of some few

petioles had been gnawed; and this was the case in 6 out of 37 which

were examined for this purpose. Worms, after having drawn in and gnawed

the basal end, often push the petioles out of their burrows; and then

drag in fresh ones, either by the base for food, or by the apex for

plugging up the mouth more effectually. Thus, out of 37 petioles

inserted by their tips, 5 had been previously drawn in by the base, for

this part had been gnawed. Again, I collected a handful of petioles

lying loose on the ground close to some plugged-up burrows, where the

surface was thickly strewed with other petioles which apparently had

never been touched by worms; and 14 out of 47 (i.e. nearly one-third),

after having had their bases gnawed had been pushed out of the burrows

and were now lying on the ground. From these several facts we may

conclude that worms draw in some petioles of the ash by the base to

serve as food, and others by the tip to plug up the mouths of their

burrows in the most efficient manner.

The petioles of Robinia pseudo-acacia vary

from 4 or 5 to nearly 12 inches in length; they are thick close to the

base before the softer parts have rotted off, and taper much towards the

upper end. They are so flexible that I have seen some few doubled up and

thus drawn into the burrows of worms. Unfortunately these petioles were

not examined until February, by which time the softer parts had

completely rotted off, so that it was impossible to ascertain whether

worms had gnawed the bases, though this is in itself probable. Out of

121 petioles extracted from burrows early in February, 68 were embedded

by the base, and 53 by the apex. On February 5 all the petioles which

had been drawn into the burrows beneath a Robinia, were pulled up; and

after an interval of eleven days, 35 petioles had been again dragged in,

19 by the base, and 16 by the apex. Taking these two lots together, 56

per cent. were drawn in by the base, and 44 per cent. by the apex. As

all the softer parts had long ago rotted off, we may feel sure,

especially in the latter case, that none had been drawn in as food. At

this season, therefore, worms drag these petioles into their burrows

indifferently by either end, a slight preference being given to the

base. This latter fact may be accounted for by the difficulty of

plugging up a burrow with objects so extremely thin as are the upper

ends. In support of this view, it may be stated that out of the 16

petioles which had been drawn in by their upper ends, the more

attenuated terminal portion of 7 had been previously broken off by some

accident.

Triangles of paper.—Elongated

triangles were cut out of moderately stiff writing-paper, which was

rubbed with raw fat on both sides, so as to prevent their becoming

excessively limp when exposed at night to rain and dew. The sides of all

the triangles were three inches in length, with the bases of 120 one

inch, and of the other 183 half an inch in length. These latter

triangles were very narrow or much acuminated. [5] As a check on the

observations presently to be given, similar triangles in a damp state

were seized by a very narrow pair of pincers at different points and at

all inclinations with reference to the margins, and were then drawn into

a short tube of the diameter of a worm-burrow. If seized by the apex,

the triangle was drawn straight into the tube, with its margins

infolded; if seized at some little distance from the apex, for instance

at half an inch, this much was doubled back within the tube. So it was

with the base and basal angles, though in this case the triangles

offered, as might have been expected, much more resistance to being

drawn in. If seized near the middle the triangle was doubled up, with

the apex and base left sticking out of the tube. As the sides of the

triangles were three inches in length, the result of their being drawn

into a tube or into a burrow in different ways, may be conveniently

divided into three groups: those drawn in by the apex or within an inch

of it; those drawn in by the base or within an inch of it; and those

drawn in by any point in the middle inch.

In order to see how the triangles would be seized by

worms, some in a damp state were given to worms kept in confinement.

They were seized in three different manners in the case of both the

narrow and broad triangles: viz., by the margin; by one of the three

angles, which was often completely engulfed in their mouths; and lastly,

by suction applied to any part of the flat surface. If lines parallel to

the base and an inch apart, are drawn across a triangle with the sides

three inches in length, it will be divided into three parts of equal

length. Now if worms seized indifferently by chance any part, they would

assuredly seize on the basal part or division far oftener than on either

of the two other divisions. For the area of the basal to the apical part

is as 5 to 1, so that the chance of the former being drawn into a burrow

by suction, will be as 5 to 1, compared with the apical part. The base

offers two angles and the apex only one, so that the former would have

twice as good a chance (independently of the size of the angles) of

being engulfed in a worm's mouth, as would the apex. It should, however,

be stated that the apical angle is not often seized by worms; the margin

at a little distance on either side being preferred. I judge of this

from having found in 40 out of 46 cases in which triangles had been

drawn into burrows by their apical ends, that the tip had been doubled

back within the burrow for a length of between 1/20th of an inch and 1

inch. Lastly, the proportion between the margins of the basal and apical

parts is as 3 to 2 for the broad, and 2½ to 2 for the narrow triangles.

From these several considerations it might certainly have been expected,

supposing that worms seized hold of the triangles by chance, that a

considerably larger proportion would have been dragged into the burrows

by the basal than by the apical part; but we shall immediately see how

different was the result.

Triangles of the above specified sizes were scattered

on the ground in many places and on many successive nights near

worm-burrows, from which the leaves, petioles, twigs, &c., with which

they had been plugged, were removed. Altogether 303 triangles were drawn

by worms into their burrows: 12 others were drawn in by both ends, but

as it was impossible to judge by which end they had been first seized,

these are excluded. Of the 303, 62 per cent, had been drawn in by the

apex (using this term for all drawn in by the apical part, one inch in

length); 15 per cent. by the middle; and 23 per cent, by the basal part.

If they had been drawn indifferently by any point, the proportion for

the apical, middle and basal parts would have been 33.3. per cent, for

each; but, as we have just seen, it might have been expected that a much

larger proportion would have been drawn in by the basal than by any

other part. As the case stands, nearly three times as many were drawn in

by the apex as by the base. If we consider the broad triangles by

themselves, 59 per cent, were drawn in by the apex, 25 per cent. by the

middle, and 16 per cent. by the base. Of the narrow triangles, 65 per

cent. were drawn in by the apex, 14 per cent. by the middle, and 21 per

cent. by the base; so that here those drawn in by the apex were more

than 3 times as many as those drawn in by the base. We may therefore

conclude that the manner in which the triangles are drawn into the

burrows is not a matter of chance.

In eight cases, two triangles had been drawn into the

same burrow, and in seven of these cases, one had been drawn in by the

apex and the other by the base. This again indicates that the result is

not determined by chance. Worms appear sometimes to revolve in the act

of drawing in the triangles, for five out of the whole lot had been

wound into an irregular spire round the inside of the burrow. Worms kept

in a warm room drew 63 triangles into their burrows; but, as in the case

of the pine-leaves, they worked in a rather careless manner, for only 44

per cent, were drawn in by the apex, 22 per cent, by the middle, and 33

per cent, by the base. In five cases, two triangles were drawn into the

same burrow.

It may be suggested with much apparent probability

that so large a proportion of the triangles were drawn in by the apex,

not from the worms having selected this end as the most convenient for

the purpose, but from having first tried in other ways and failed. This

notion was countenanced by the manner in which worms in confinement were

seen to drag about and drop the triangles; but then they were working

carelessly. I did not at first perceive the importance of this subject,

but merely noticed that the bases of those triangles which had been

drawn in by the apex, were generally clean and not crumpled. The subject

was afterwards attended to carefully. In the first place several

triangles which had been drawn in by the basal angles, or by the base,

or a little above the base, and which were thus much crumpled and

dirtied, were left for some hours in water and were then well shaken

while immersed; but neither the dirt nor the creases were thus removed.

Only slight creases could be obliterated, even by pulling the wet

triangles several times through my fingers. Owing to the slime from the

worms' bodies, the dirt was not easily washed off. We may therefore

conclude that if a triangle, before being dragged in by the apex, had

been dragged into a burrow by its base with even a slight degree of

force, the basal part would long retain its creases and remain dirty.

The condition of 89 triangles (65 narrow and 24 broad ones), which had

been drawn in by the apex, was observed; and the bases of only 7 of them

were at all creased, being at the same time generally dirty. Of the 82

uncreased triangles, 14 were dirty at the base; but it does not follow

from this fact that these had first been dragged towards the burrows by

their bases; for the worms sometimes covered large portions of the

triangles with slime, and these when dragged by the apex over the ground

would be dirtied; and during rainy weather, the triangles were often

dirtied over one whole side or over both sides. If the worms had dragged

the triangles to the mouths of their burrows by their bases, as often as

by their apices, and had then perceived, without actually trying to draw

them into the burrow, that the broader end was not well adapted for this

purpose—even in this case a large proportion would probably have had

their basal ends dirtied. We may therefore infer—improbable as is the

inference—that worms are able by some means to judge which is the best

end by which to draw triangles of paper into their burrows.

The percentage results of the foregoing observations

on the manner in which worms draw various kinds of objects into the

mouths of their burrows may be abridged as follows:

| Nature of Object. |

Drawn into the

burrows, by or near the apex. |

Drawn in, by or

near the middle. |

Drawn in, by or

near the base. |

| Leaves of various kinds . . . |

80 |

11 |

9 |

| ——— of the Lime, basal margin

of blade broad, apex acuminated . . . . |

79 |

17 |

4 |

| ——— of a Laburnum, basal part

of blade as narrow as, or sometimes little narrower than the

apical part |

63 |

10 |

27 |

| ——— of the Rhododendron,

basal part of blade often narrower than the apical part. . . |

34 |

.. |

66 |

| ——— of Pine-trees, consisting

of two needles arising from a common base . . . |

. . |

. . |

100 |

| Petioles of a Clematis,

somewhat pointed at the apex, and blunt at the base . . |

76 |

. . |

24 |

| ——— of the Ash, the thick

basal end often drawn in to serve as food . . . . |

48.5 |

. . |

51.5 |

| ——— of Robinia, extremely

thin, especially towards the apex, so as to be ill-fitted

for plugging up the burrows . |

44 |

. . |

56 |

| Triangles of paper, of the

two sizes . |

62 |

15 |

23 |

| ——— of the broad ones alone. |

59 |

25 |

16 |

| ——— of the narrow ones alone |

65 |

14 |

21 |

If we consider these several cases, we can hardly

escape from the conclusion that worms show some degree of intelligence

in their manner of plugging up their burrows. Each particular object is

seized in too uniform a manner, and from causes which we can generally

understand, for the result to be attributed to mere chance. That every

object has not been drawn in by its pointed end, may be accounted for by

labour having been saved through some being inserted by their broader or

thicker ends. No doubt worms are led by instinct to plug up their

burrows; and it might have been expected that they would have been led

by instinct how best to act in each particular case, independently of

intelligence. We see how difficult it is to judge whether intelligence

comes into play, for even plants might sometimes be thought to be thus

directed; for instance when displaced leaves re-direct their upper

surfaces towards the light by extremely complicated movements and by the

shortest course. With animals, actions appearing due to intelligence may

be performed through inherited habit without any intelligence, although

aboriginally thus acquired. Or the habit may have been acquired through

the preservation and inheritance of beneficial variations of some other

habit; and in this case the new habit will have been acquired

independently of intelligence throughout the whole course of its

development. There is no à priori improbability in worms having

acquired special instincts through either of these two latter means.

Nevertheless it is incredible that instincts should have been developed

in reference to objects, such as the leaves or petioles of foreign

plants, wholly unknown to the progenitors of the worms which act in the

described manner. Nor are their actions so unvarying or inevitable as

are most true instincts.

As worms are not guided by special instincts in each

particular case, though possessing a general instinct to plug up their

burrows, and as chance is excluded, the next most probable conclusion

seems to be that they try in many different ways to draw in objects, and

at last succeed in some one way. But it is surprising that an animal so

low in the scale as a worm should have the capacity for acting in this

manner, as many higher animals have no such capacity. For instance, ants

may be seen vainly trying to drag an object transversely to their

course, which could be easily drawn longitudinally; though after a time

they generally act in a wiser manner. M. Fabre states [6] that a Sphex—an

insect belonging to the same highly-endowed order with ants—stocks its

nest with paralysed grasshoppers, which are invariably dragged into the

burrow by their antennæ. When these were cut off close to the head, the

Sphex seized the palpi; but when these were likewise cut off, the

attempt to drag its prey into the burrow was given up in despair. The

Sphex had not intelligence enough to seize one of the six legs or the

ovipositor of the grasshopper, which, as M. Fabre remarks, would have

served equally well. So again, if the paralysed prey with an egg

attached to it be taken out of the cell, the Sphex after entering and

finding the cell empty, nevertheless closes it up in the usual elaborate

manner. Bees will try to escape and go on buzzing for hours on a window,

one half of which has been left open. Even a pike continued during three

months to dash and bruise itself against the glass sides of an aquarium,

in the vain attempt to seize minnows on the opposite side. [7] A

cobrasnake was seen by Mr. Layard [8] to act much more wisely than

either the pike or the Sphex; it had swallowed a toad lying within a

hole, and could not withdraw its head; the toad was disgorged, and began

to crawl away; it was again swallowed and again disgorged; and now the

snake had learnt by experience, for it seized the toad by one of its

legs and drew it out of the hole. The instincts of even the higher

animals are often followed in a senseless or purposeless manner: the

weaver-bird will perseveringly wind threads through the bars of its

cage, as if building a nest: a squirrel will pat nuts on a wooden floor,

as if he had just buried them in the ground: a beaver will cut up logs

of wood and drag them about, though there is no water to dam up; and so

in many other cases.

Mr. Romanes who has specially studied the minds of

animals, believes that we can safely infer intelligence, only when we

see an individual profiting by its own experience. By this test the

cobra showed some intelligence; but this would have been much plainer if

on a second occasion he had drawn a toad out of a hole by its leg. The

Sphex failed signally in this respect. Now if worms try to drag objects

into their burrows first in one way and then in another, until they at

last succeed, they profit, at least in each particular instance, by

experience.

But evidence has been advanced showing that worms do

not habitually try to draw objects into their burrows in many different

ways. Thus half-decayed lime-leaves from their flexibility could have

been drawn in by their middle or basal parts, and were thus drawn into

the burrows in considerable numbers; yet a large majority were drawn in

by or near the apex. The petioles of the Clematis could certainly have

been drawn in with equal ease by the base and apex; yet three times and

in certain cases five times as many were drawn in by the apex as by the

base. It might have been thought that the foot-stalks of leaves would

have tempted the worms as a convenient handle; yet they are not largely

used, except when the base of the blade is narrower than the apex. A

large number of the petioles of the ash are drawn in by the base; but

this part serves the worms as food. In the case of pine-leaves worms

plainly show that they at least do not seize the leaf by chance; but

their choice does not appear to be determined by the divergence of the

two needles, and the consequent advantage or necessity of drawing them

into their burrows by the base. With respect to the triangles of paper,

those which had been drawn in by the apex rarely had their bases creased

or dirty; and this shows that the worms had not often first tried to

drag them in by this end.

If worms are able to judge, either before drawing or

after having drawn an object close to the mouths of their burrows, how

best to drag it in, they must acquire some notion of its general shape.

This they probably acquire by touching it in many places with the

anterior extremity of their bodies, which serves as a tactile organ. It

may be well to remember how perfect the sense of touch becomes in a man

when born blind and deaf, as are worms. If worms have the power of

acquiring some notion, however rude, of the shape of an object and of

their burrows, as seems to be the case, they deserve to be called

intelligent; for they then act in nearly the same manner as would a man

under similar circumstances.

To sum up, as chance does not determine the manner in

which objects are drawn into the burrows, and as the existence of

specialized instincts for each particular case cannot be admitted, the

first and most natural supposition is that worms try all methods until

they at last succeed; but many appearances are opposed to such a

supposition. One alternative alone is left, namely, that worms, although

standing low in the scale of organization, possess some degree of

intelligence. This will strike every one as very improbable; but it may

be doubted whether we know enough about the nervous system of the lower

animals to justify our natural distrust of such a conclusion. With

respect to the small size of the cerebral ganglia, we should remember

what a mass of inherited knowledge, with some power of adapting means to

an end, is crowded into the minute brain of a worker-ant.

Means by which worms excavate their burrows.—This

is effected in two ways; by pushing away the earth on all sides, and by

swallowing it. In the former case, the worm inserts the stretched out

and attenuated anterior extremity of its body into any little crevice,

or hole; and then, as Perrier remarks, [9] the pharynx is pushed

forwards into this part, which consequently swells and pushes away the

earth on all sides. The anterior extremity thus serves as a wedge. It

also serves, as we have before seen, for prehension and suction, and as

a tactile organ. A worm was placed on loose mould, and it buried itself

in between two and three minutes. On another occasion four worms

disappeared in 15 minutes between the sides of the pot and the earth,

which had been moderately pressed down. On a third occasion three large

worms and a small one were placed on loose mould well mixed with fine

sand and firmly pressed down, and they all disappeared, except the tail

of one, in 35 minutes. On a fourth occasion six large worms were placed

on argillaceous mud mixed with sand firmly pressed down, and they

disappeared, except the extreme tips of the tails of two of them, in 40

minutes. In none of these cases, did the worms swallow, as far as could

be seen, any earth. They generally entered the ground close to the sides

of the pot.

A pot was next filled with very fine ferruginous sand,

which was pressed down, well watered, and thus rendered extremely

compact. A large worm left on the surface did not succeed in penetrating

it for some hours, and did not bury itself completely until 25 hrs. 40

min. had elapsed. This was effected by the sand being swallowed, as was

evident by the large quantity ejected from the vent, long before the

whole body had disappeared. Castings of a similar nature continued to be

ejected from the burrow during the whole of the following day.

As doubts have been expressed by some writers whether

worms ever swallow earth solely for the sake of making their burrows,

some additional cases may be given. A mass of fine reddish sand, 23

inches in thickness, left on the ground for nearly two years, had been

penetrated in many places by worms; and their castings consisted partly

of the reddish sand and partly of black earth brought up from beneath

the mass. This sand had been dug up from a considerable depth, and was

of so poor a nature that weeds could not grow on it. It is therefore

highly improbable that it should have been swallowed by the worms as

food. Again in a field near my house the castings frequently consist of

almost pure chalk, which lies at only a little depth beneath the

surface; and here again it is very improbable that the chalk should have

been swallowed for the sake of the very little organic matter which

could have percolated into it from the poor overlying pasture. Lastly, a

casting thrown up through the concrete and decayed mortar between the

tiles, with which the now ruined aisle of Beaulieu Abbey had formerly

been paved, was washed, so that the coarser matter alone was left. This

consisted of grains of quartz, micaceous slate, other rocks, and bricks

or tiles, many of them from 1/20 to 1/10 inch in diameter. No one will

suppose that these grains were swallowed as food, yet they formed more

than half of the casting, for they weighed 19 grains, the whole casting

having weighed 33 grains. Whenever a worm burrows to a depth of some

feet in undisturbed compact ground, it must form its passage by

swallowing the earth; for it is incredible that the ground could yield

on all sides to the pressure of the pharynx when pushed forwards within

the worm's body.

That worms swallow a larger quantity of earth for the

sake of extracting any nutritious matter which it may contain than for

making their burrows, appears to me certain. But as this old belief has

been doubted by so high an authority as Claparède, evidence in its

favour must be given in some detail. There is no à priori

improbability in such a belief, for besides other annelids, especially

the Arenicola marina, which throws up such a profusion of

castings on our tidal sands, and which it is believed thus subsists,

there are animals belonging to the most distinct classes, which do not

burrow, but habitually swallow large quantities of sand; namely the

molluscan Onchidium and many Echinoderms. [10]

If earth were swallowed only when worms deepened their

burrows or made new ones, castings would be thrown up only occasionally;

but in many places fresh castings may be seen every morning, and the

amount of earth ejected from the same burrow on successive days is

large. Yet worms do not burrow to a great depth, except when the weather

is very dry or intensely cold. On my lawn the black vegetable mould is

only about 5 inches in thickness, and overlies light coloured or reddish

clayey soil: now when castings are thrown up in the greatest profusion,

only a small proportion are light coloured, and it is incredible that

the worms should daily make fresh burrows in every direction in the thin

superficial layer of dark-coloured humus, unless they obtained nutriment

of some kind from it. I have observed a strictly analogous case in a

field near my house where bright red clay lay close beneath the surface.

Again on one part of the Downs near Winchester the vegetable mould

overlying the chalk was found to be only from 3 to 4 inches in

thickness; and the many castings here ejected were as black as ink and

did not effervesce with acids; so that the worms must have confined

themselves to this thin superficial layer of mould, of which large

quantities were daily swallowed. In another place at no great distance

the castings were white; and why the worms should have burrowed into the

chalk in some places and not in others, I am unable to conjecture.

Two great piles of leaves had been left to decay in my

grounds, and months after their removal, the bare surface, several yards

in diameter, was so thickly covered during several months with castings

that they formed an almost continuous layer; and the large number of

worms which lived here must have subsisted during these months on

nutritious matter contained in the black earth.

The lowest layer from another pile of decayed leaves

mixed with some earth was examined under a high power, and the number of

spores of various shapes and sizes which it contained was astonishingly

great; and these crushed in the gizzards of worms may largely aid in

supporting them. Whenever castings are thrown up in the greatest number,

few or no leaves are drawn into the burrows; for instance the turf along

a hedgerow, about 200 yards in length, was daily observed in the autumn

during several weeks, and every morning many fresh castings were seen;

but not a single leaf was drawn into these burrows. These castings from

their blackness and from the nature of the subsoil could not have been

brought up from a greater depth than 6 or 8 inches. On what could these

worms have subsisted during this whole time, if not on matter contained

in the black earth? On the other hand, whenever a large number of leaves

are drawn into the burrows, the worms seem to subsist chiefly on them,

for few earth-castings are then ejected on the surface. This difference

in the behaviour of worms at different times, perhaps explains a

statement by Claparède, namely, that triturated leaves and earth are

always found in distinct parts of their intestines.

Worms sometimes abound in places where they can rarely

or never obtain dead or living leaves; for instance, beneath the

pavement in well-swept courtyards, into which leaves are only

occasionally blown. My son Horace examined a house, one corner of which

had subsided; and he found here in the cellar, which was extremely damp,

many small worm-castings thrown up between the stones with which the

cellar was paved; and in this case it is improbable that the worms could

ever have obtained leaves.

But the best evidence, known to me, of worms

subsisting for at least considerable periods of time solely on the

organic matter contained in earth, is afforded by some facts

communicated to me by Dr. King. Near Nice large castings abound in

extraordinary numbers, so that 5 or 6 were often found within the space

of a square foot. They consist of fine, pale-coloured earth, containing

calcareous matter, which after having passed through the bodies of worms

and being dried, coheres with considerable force. I have reason to

believe that these castings had been formed by species of Perichæta,

which have been naturalised here from the East. [11] They rise like

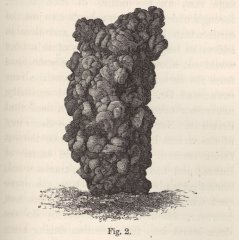

towers (see Fig. 2), with their summits often a little broader than

their bases, sometimes to a height of above 3 and often to a height of

2½ inches.

Fig. 2. Tower-like casting from near Nice,

constructed of earth, voided probably by a species of Perichæta: of

natural size, copied from a photograph.

The tallest of those which were measured was 3.3 inch

in height and 1 in diameter. A small cylindrical passage runs up the

centre of each tower, through which the worm ascends to eject the earth

which it has swallowed, and thus to add to its height. A structure of

this kind would not allow leaves being easily dragged from the

surrounding ground into the burrows; and Dr. King, who looked carefully,

never saw even a fragment of a leaf thus drawn in. Nor could any trace

be discovered of the worms having crawled down the exterior surfaces of

the towers in search of leaves; and had they done so, tracks would

almost certainly have been left on the upper part whilst it remained

soft. It does not, however, follow that these worms do not draw leaves

into their burrows during some other season of the year, at which time

they would not build up their towers.

From the several foregoing cases, it can hardly be

doubted that worms swallow earth, not only for the sake of making their

burrows, but for obtaining food. Hensen, however, concludes from his

analyses of humus that worms probably could not live on ordinary

vegetable mould, though he admits that they might be nourished to some

extent by leaf-mould. [12] But we have seen that worms eagerly devour

raw meat, fat, and dead worms; and ordinary mould can hardly fail to

contain many ova, larvæ, and small living or dead creatures, spores of

cryptogamic plants, and micrococci, such as those which give rise to

saltpetre. These various organisms, together with some cellulose from

any leaves and roots not utterly decayed, might well account for such

large quantities of mould being swallowed by worms. It may be worth

while here to recall the fact that certain species of Utricularia, which

grow in damp places in the tropics, possess bladders beautifully

constructed for catching minute subterranean animals; and these traps

would not have been developed unless many small animals inhabited such

soil.

The depth to which worms penetrate, and the

construction of their burrows. — Although

worms usually live near the surface, yet they burrow to a considerable

depth during long-continued dry weather and severe cold. In Scandinavia,

according to Eisen, and in Scotland, according to Mr. Lindsay Carnagie,

the burrows run down to a depth of from 7 to 8 feet; in North Germany,

according to Hoffmeister, from 6 to 8 feet, but Hensen says, from 3 to 6

feet. This latter observer has seen worms frozen at a depth of 1½ feet

beneath the surface. I have not myself had many opportunities for

observation, but I have often met with worms at depths of 3 to 4 feet.

In a bed of fine sand overlying the chalk, which had never been

disturbed, a worm was cut into two at 55 inches, and another was found

here in December at the bottom of its burrow, at 61 inches beneath the

surface. Lastly, in earth near an old Roman Villa, which had not been

disturbed for many centuries, a worm was met with at a depth of 66

inches; and this was in the middle of August.

The burrows run down perpendicularly, or more commonly

a little obliquely. They are said sometimes to branch, but as far as I

have seen this does not occur, except in recently dug ground and near

the surface. They are generally, or as I believe invariably, lined with

a thin layer of fine, dark-coloured earth voided by the worms; so that

they must at first be made a little wider than their ultimate diameter.

I have seen several burrows in undisturbed sand thus lined at a depth of

4 ft. 6 in.; and others close to the surface thus lined in recently dug

ground. The walls of fresh burrows are often dotted with little globular

pellets of voided earth, still soft and viscid; and these, as it

appears, are spread out on all sides by the worm as it travels up or

down its burrow. The lining thus formed becomes very compact and smooth

when nearly dry, and closely fits the worm's body. The minute reflexed

bristles which project in rows on all sides from the body, thus have

excellent points of support; and the burrow is rendered well adapted for

the rapid movement of the animal. The lining appears also to strengthen

the walls, and perhaps saves the worm's body from being scratched. I

think so because several burrows which passed through a layer of sifted

coal-cinders, spread over turf to a thickness of 1½ inch, had been thus

lined to an unusual thickness. In this case the worms, judging from the

castings, had pushed the cinders away on all sides and had not swallowed

any of them. In another place, burrows similarly lined, passed through a

layer of coarse coal-cinders, 3½ inches in thickness. We thus see that

the burrows are not mere excavations, but may rather be compared with

tunnels lined with cement.

The mouths of the burrow are in addition often lined

with leaves; and this is an instinct distinct from that of plugging them

up, and does not appear to have been hitherto noticed. Many leaves of

the Scotch-fir or pine (Pinus sylvestris) were given to worms

kept in confinement in two pots; and when after several weeks the earth

was carefully broken up, the upper parts of three oblique burrows were

found surrouuded for lengths of 7, 4, and 3½ inches with pine-leaves,

together with fragments of other leaves which had been given the worms

as food. Glass beads and bits of tile, which had been strewed on the

surface of the soil, were stuck into the interstices between the

pine-leaves; and these interstices were likewise plastered with the

viscid castings voided by the worms. The structures thus formed cohered

so well, that I succeeded in removing one with only a little earth

adhering to it. It consisted of a slightly curved cylindrical case, the

interior of which could be seen through holes in the sides and at either

end. The pine-leaves had all been drawn in by their bases; and the sharp

points of the needles had been pressed into the lining of voided earth.

Had this not been effectually done, the sharp points would have

prevented the retreat of the worms into their burrows; and these

structures would have resembled traps armed with converging points of

wire, rendering the ingress of an animal easy and its egress difficult

or impossible. The skill shown by these worms is noteworthy and is the

more remarkable, as the Scotch pine is not a native of this district.

After having examined these burrows made by worms in

confinement, I looked at those in a flower-bed near some Scotch pines.

These had all been plugged up in the ordinary manner with the leaves of

this tree, drawn in for a length of from 1 to 1½ inch; but the mouths of

many of them were likewise lined with them, mingled with fragments of

other kinds of leaves, drawn in to a depth of 4 or 5 inches. Worms often

remain, as formerly stated, for a long time close to the mouths of their

burrows, apparently for warmth; and the basket-like structures formed of

leaves would keep their bodies from coming into close contact with the

cold damp earth. That they habitually rested on the pine-leaves, was

rendered probable by their clean and almost polished surfaces.

The burrows which run far down into the ground,

generally, or at least often, terminate in a little enlargement or

chamber. Here, according to Hoffmeister, one or several worms pass the

winter rolled up into a ball. Mr. Lindsay Carnagie informed me (1838)

that he had examined many burrows over a stone-quarry in Scotland, where

the overlying boulder-clay and mould had recently been cleared away, and

a little vertical cliff thus left. In several cases the same burrow was

a little enlarged at two or three points one beneath the other; and all

the burrows terminated in a rather large chamber, at a depth of 7 or 8

feet from the surface. These chambers contained many small sharp bits of

stone and husks of flax-seeds. They must also have contained living

seeds, for on the following spring Mr. Carnagie saw grass-plants

sprouting out of some of the intersected chambers. I found at Abinger in

Surrey two burrows terminating in similar chambers at a depth of 36 and

41 inches, and these were lined or paved with little pebbles, about as

large as mustard seeds; and in one of the chambers there was a decayed

oat-grain, with its husk. Hensen likewise states that the bottoms of the

burrows are lined with little stones; and where these could not be

procured, seeds, apparently of the pear, had been used, as many as

fifteen having been carried down into a single burrow, one of which had

germinated. [13] We thus see how easily a botanist might be deceived who

wished to learn how long deeply buried seeds remained alive, if he were

to collect earth from a considerable depth, on the supposition that it

could contain only seeds which had long lain buried. It is probable that

the little stones, as well as the seeds, are carried down from the

surface by being swallowed; for a surprising number of glass beads, bits

of tile and of glass were certainly thus carried down by worms kept in

pots; but some may have been carried down within their mouths. The sole

conjecture which I can form why worms line their winter-quarters with

little stones and seeds, is to prevent their closely coiled-up bodies

from coming into close contact with the surrounding cold soil; and such

contact would perhaps interfere with their respiration which is effected

by the skin alone.

A worm after swallowing earth, whether for making its

burrow or for food, soon comes to the surface to empty its body. The

ejected earth is thoroughly mingled with the intestinal secretions, and

is thus rendered viscid. After being dried it sets hard. I have watched

worms during the act of ejection, and when the earth was in a very

liquid state it was ejected in little spurts, and when not so liquid by

a slow peristaltic movement. It is not cast indifferently on any side,

but with some care, first on one and then on another side; the tail

being used almost like a trowel.

As soon as a little heap is formed, the worm

apparently avoids, for the sake of safety, protruding its tail; and the

earthy matter is forced up through the previously deposited soft mass.

The mouth of the same burrow is used for this purpose for a considerable

time. In the case of the tower-like castings (see Fig. 2) near Nice, and

of the similar but still taller towers from Bengal (hereafter to be

described and figured) a considerable degree of skill is exhibited in

their construction. Dr. King also observed that the passage up these

towers hardly ever ran in the same exact line with the underlying

burrow, so that a thin cylindrical object such as a haulm of grass,

could not be passed down the tower into the burrow; and this change of

direction probably serves in some manner as a protection. When a worm

comes to the surface to eject earth, the tail protrudes, but when it

collects leaves its head must protrude. Worms therefore must have the

power of turning round in their closely-fitting burrows; and this, as it

appears to us, would be a difficult feat.

Worms do not always eject their castings on the

surface of the ground. When they can find any cavity, as when burrowing

in newly turned-up earth, or between the stems of banked-up plants, they

deposit their castings in such places. So again any hollow beneath a

large stone lying on the surface of the ground, is soon filled up with

their castings. According to Hensen, old burrows are habitually used for

this purpose; but as far as my experience serves, this is not the case,

excepting with those near the surface in recently dug ground. I think

that Hensen may have been deceived by the walls of old burrows, lined

with black earth, having sunk in or collapsed; for black streaks are

thus left, and these are conspicuous when passing through light-coloured

soil, and might be mistaken for completely filled-up burrows.

It is certain that old burrows collapse in the course

of time; for as we shall see in the next chapter, the fine earth voided

by worms, if spread out uniformly, would form in many places in the

course of a year a layer 1/5; of an inch in thickness; so that at any

rate this large amount is not deposited within the old unused burrows.

If the burrows did not collapse, the whole ground would be first thickly

riddled with holes to a depth of about ten inches, and in fifty years a

hollow unsupported space, ten inches in depth, would be left. The holes

left by the decay of successively formed roots of trees and plants must

likewise collapse in the course of time.

The burrows of worms run down perpendicularly or a

little obliquely, and where the soil is at all argillaceous, there is no

difficulty in believing that the walls would slowly flow or slide

inwards during very wet weather. When, however, the soil is sandy or

mingled with many small stones, it can hardly be viscous enough to flow

inwards during even the wettest weather; but another agency may here

come into play. After much rain the ground swells, and as it cannot

expand laterally, the surface rises; during dry weather it sinks again.

For instance, a large flat stone laid on the surface of a field sank

3.33 mm. whilst the weather was dry between May 9th and June 13th, and

rose 1.91 mm. between September 7th and 19th, much rain having fallen

during the latter part of this time. During frosts and thaws

the movements were twice as great. These observations were made by

my son Horace, who will hereafter publish an account of the movements of

this stone during successive wet and dry seasons, and of the effects of

its being undermined by worms. Now when the ground swells, if it be

penetrated by cylindrical holes, such as worm-burrows, their walls will

tend to yield and be pressed inwards; and the yielding will be greater

in the deeper parts (supposing the whole to be equally moistened) from

the greater weight of the superincumbent soil which has to be raised,

than in the parts near the surface. When the ground dries, the walls

will shrink a little and the burrows will be a little enlarged. Their

enlargement, however, through the lateral contraction of the ground,

will not be favoured, but rather opposed, by the weight of the

superincumbent soil.

Distribution of Worms.—Earth-worms

are found in all parts of the world, and some of the genera have an

enormous range. [14] They inhabit the most isolated islands; they abound

in Iceland, and are known to exist in the West Indies, St. Helena,

Madagascar, New Caledonia and Tahiti. In the Antarctic regions, worms

from Kerguelen Land have been described by Ray Lankester; and I found

them in the Falkland Islands. How they reach such isolated islands is at

present quite unknown. They are easily killed by salt-water, and it does

not appear probable that young worms or their egg-capsules could be

carried in earth adhering to the feet or beaks of land-birds. Moreover

Kerguelen Land is not now inhabited by any land-bird.

In this volume we are chiefly concerned with the earth

cast up by worms, and I have gleaned a few facts on this subject with

respect to distant lands. Worms throw up plenty of castings in the

United States. In Venezuela, castings, probably ejected by species of

Urochæta, are common in the gardens and fields, but not in the forests,

as I hear from Dr. Ernst of Caracas. He collected 156 castings from the

court-yard of his house, having an area of 200 square yards. They varied

in bulk from half a cubic centimeter to five cubic centimeters, and were

on an average three cubic centimeters. They were, therefore of small

size in comparison with those often found in England; for six large

castings from a field near my house averaged 16 cubic centimeters.

Several species of earth-worms are common in St. Catharina in South

Brazil, and Fritz Müller informs me "that in most parts of the forests

and pasture-lands, the whole soil, to a depth of a quarter of a metre,

looks as if it had passed repeatedly through the intestines of

earth-worms, even where hardly any castings are to be seen on the

surface." A gigantic but very rare species is found there, the burrows

of which are sometimes even two centimeters or nearly 4/5; of an inch in

diameter, and which apparently penetrate the ground to a great depth.

In the dry climate of New South Wales, I hardly

expected that worms would be common; but Dr. G. Krefft of Sydney, to