PALESTINE -- PEACE NOT APARTHEID |

|

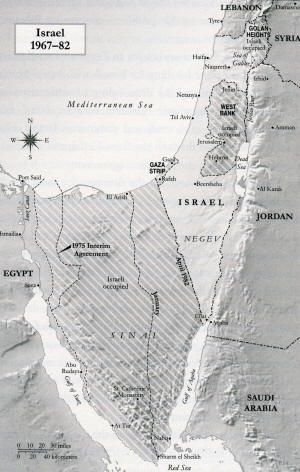

Chapter 3: MY PRESIDENCY, 1977-81 The 1973 war introduced major changes in the character of the Middle East. The effective performance of the Egyptian and Syrian armies increased the stature of both President Anwar al-Sadat of Egypt and President Hafez al- Assad of Syria. The Arab states demonstrated that they were willing to use oil as a weapon in support of Arab interests, through embargo and price increases. In Israel, in June 1974, Prime Minister Golda Meir resigned and Yitzhak Rabin took her place. Also, in October, Arab leaders unanimously proclaimed the Palestine Liberation Organization as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, with Yasir Arafat as its leader. Now the Palestinians were to be seen as a people who could speak for themselves. The PLO became a powerful political entity, able to arouse strong support in international forums from the Arabs, the Soviet Union, most Third World countries, and many others. However, U.S. government leaders pledged not to recognize or negotiate with the PLO until the organization officially acknowledged Israel's right to exist and accepted U.N. Resolution 242, which confirmed Israel's existence within its 1949 borders. A more important problem was that the PLO's rejection of Israel was shared by the leaders of all Arab nations, following four wars in the previous twenty-five years. These were the events that I monitored after returning home from my first visit to Israel and during my race for president. It was a rare day on the campaign trail that I did not receive questions from Jewish citizens about the interests of Israel, and my growing team of issue analysts provided me with briefing papers that I could study. I made repeated promises that I would seek to invigorate the dormant peace effort, and after I was elected and before my inauguration I made a speech at the Smithsonian Institution in which I listed this as a major foreign policy goal. Since the United States had to play a strong role in any peace effort, I reviewed the official positions of my predecessors on the key issues. Our nation's constant policy had been predicated on a few key United Nations Security Council resolutions, notably 242 of 1967 (Appendix 1) and 338 of 1973 (Appendix 2). Approved unanimously and still applicable, their basic premise is that Israel's acquisition of territory by force is illegal and that Israel must withdraw from occupied territories; that Israel has the right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries; that the refugee problem must be settled; and that the international community should assist with negotiations to achieve a just and durable peace in the Middle East. More specifically, U.S. policy was that Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza were "illegal and obstacles to peace." One of my first and most controversial public statements came in March 1977, just a few weeks after I became president, when I reviewed these same premises and added, "There has to be a homeland provided for the Palestinian refugees who have suffered for many, many years." This would be the first move toward supporting a Palestinian state. Two weeks later, President Sadat came to Washington for a state visit, and after the official banquet he and I went upstairs to the living quarters in the White House. During a long, private conversation it became obvious that his inclination to work with me on peace negotiations was already well developed, but he had not decided on any firm plan to reach what might become our common goal. Sadat told me plainly that he was willing to take bold steps toward peace, all of them based on the prevailing U.N. Security Council resolutions. We discussed some of the specific elements of possible direct negotiations in the future: Israel's permanent boundaries, the status of Jerusalem, Palestinian rights, and -- almost inconceivable at the time -- free trade and open borders between the two nations, plus full diplomatic recognition and the exchange of ambassadors. Menachem Begin replaced Yitzhak Rabin as prime minister a month later, and I quickly learned all I could about Israel's new leader. His surprising victory ended the uninterrupted domination of the Labor Party since Israel's independence. Begin had put together a majority coalition that accepted his premise that the land in Gaza and the West Bank belonged rightfully to the State of Israel and should not be exchanged for a permanent peace agreement with the Arabs. Public opinion varied widely, but there was no doubt in 1977 that a more hawkish attitude now prevailed in the government of Israel. I was deeply concerned but sent him personal congratulations and an invitation to visit me in Washington. Although many factors had influenced the outcome of the Israeli election, age and ethnic differences strongly favored the Likud over the Labor alignment. Oriental Jews (known as Sephardim), whose families had come from the Middle East and Africa, gave the Likud coalition parties a political margin in 1977, and they were inclined to support a much more militant policy in dealing with the occupied territories. Although Begin was not one of them by birth, his philosophy and demeanor were attractive to the Sephardic voters. Also, the Sephardim were generally younger, more conservative, and nearer the bottom of the economic ladder and they resented the more prosperous and sophisticated Jewish immigrants from Europe and America (known as Ashkenazim), who had furnished almost all of Israel's previous leaders. The Sephardic families had a higher birth rate than the Ashkenazim, and now, combined with many immigrants, they had become a strong political force. The personal character of Menachem Begin was also a major factor in the victory. After he and his family suffered persecution in Eastern Europe and Siberia for his political activity as a Zionist, he was released from a Soviet prison and went to Palestine in 1942. He became the leader of a militant underground group called the Irgun, which espoused the maximum demands of Zionism. These included driving British forces out of Palestine. He fought with every weapon available against the British, who branded him as the preeminent terrorist in the region. A man of personal courage and single-minded devotion to his goals, he took pride in being a "fighting Jew." I realized that Israel's new prime minister, with whom I would be dealing, would be prepared to resort to extreme measures to achieve the goals in which he believed. In Israel, Begin put forward clear and blunt answers to complex questions about peace and war, religion, the Palestinians, finance, and economics. I expected him to have a clear idea of when he might yield and what he would not give up in negotiations with his Arab neighbors and the United States. However, when he came to Washington to meet with me, I found the prime minister quite willing to pursue some of the major goals that I had discussed with Sadat. I also had definitive discussions with King Hussein of Jordan and President Assad of Syria, but it was obvious that they would not be willing to participate in the kind of peace effort that Sadat, Begin, and I had discussed. The economic and political pressures among the Arab leaders to maintain a unanimous condemnation of Israel were overwhelming. The PLO was out of diplomatic bounds for me, still officially classified by the United States as a terrorist organization. Despite this restraint, I sought through unofficial channels to induce Arafat to accept the key U.N. resolutions so that the PLO could join in peace efforts, but he refused. I sent Sadat a handwritten letter telling him how "extremely important -- perhaps vital" it was for us to work together, and he and I discussed various possibilities by telephone. In November 1977, Sadat made a dramatic peace initiative by going directly to Jerusalem. Begin received Sadat graciously and listened with apparent composure while the Egyptian president laid down in no uncertain terms the strongest Arab position, which included Israel's immediate withdrawal from all occupied territories and the right of return of Palestinians to their former homes. I found it interesting that Sadat decided not to follow the counsel of his advisers that he make the speech in English for the world audience, but to deliver it in Arabic for the benefit of his Arab neighbors. The symbolism of his presence obscured the harshness of his actual words, so the reaction in Western nations was overwhelmingly favorable and the Israeli public responded with excitement and enthusiasm. The responses of the Saudis, Jordanians, and some of the other moderate Arab leaders were cautious, but Syria broke diplomatic relations with Egypt, and high officials in Damascus, Baghdad, Tripoli, and the PLO called for Sadat's assassination. Prime Minister Begin came to the White House to discuss specific peace proposals, and there was a flurry of meetings between the Egyptians and Israelis that culminated shortly after Christmas in a return visit by Begin to Egypt. Sadat reported to me that the session was completely unsatisfactory, an apparently fatal setback for his peace initiative, because Begin was insisting that Israeli settlements must remain on Egyptian land in the Sinai. It appeared that the only permanent result of Sadat's move was an end to any prospect for an international peace conference involving the Soviets. I consulted with as many Arab leaders as possible on a fast New Year's trip to the region and found them somewhat supportive of Sadat in private but quite critical in their public statements, honoring a pledge of unanimity with their other Arab brothers. During the early part of 1978, Sadat sent me a private message that he intended to come to the United States and publicly condemn Begin as a betrayer of the peace process. Rosalynn and I invited Anwar and his wife, Jehan, to Camp David for a personal visit, and after a weekend of intense talks, Sadat was convinced to cancel his planned speech and join me in search of an agreement. Unfortunately, my working relationship with Menachem Begin became even more difficult in March, when the PLO launched an attack on Israel from a base in Southern Lebanon. A sightseeing bus was seized and thirty-five Israelis were killed. I publicly condemned this outrageous act, but my sympathy was strained three days later when Israel invaded Lebanon and used American-made antipersonnel cluster bombs against Beirut and other urban centers, killing hundreds of civilians and leaving thousands homeless. I considered this major invasion to be all overreaction to the PLO attack, a serious threat to peace in the region, and perhaps part of a plan to establish a permanent Israeli presence in Southern Lebanon. Also, such use of American weapons violated a legal requirement that armaments sold by us be used only for Israeli defense against an attack. After consulting with key supporters of Israel in the U.S. Senate, I informed Prime Minister Begin that if Israeli forces remained in Lebanon, I would have to notify Congress, as required by law, that U.S. weapons were being used illegally in Lebanon, which would automatically cut off all military aid to Israel. Also, I instructed the State Department to prepare a U.N. Security Council resolution condemning Israel's action. Israeli forces withdrew, and United Nations troops came in to replace them in Southern Lebanon, adequate to restrain further PLO attacks on Israeli citizens. Our efforts to rejuvenate the overall peace process were fruitless during the spring and summer. My next act was almost one of desperation. I decided to invite both Begin and Sadat to Camp David so that we could be away from routine duties for a few days and, in relative isolation, I could act as mediator between the two national delegations. They accepted without delay, and on September 4 we began what evolved into a thirteen-day session, which involved teams of about fifty on each side. My aim was to have Israelis and Egyptians understand and accept the compatibility of many of their goals and the advantages to both nations in resolving their differences. We had to address such basic questions as Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories, Palestinian rights, Israel's security, an end to the Arab trade embargo, open borders between Israel and Egypt, the rights of Israeli ships to transit the Suez Canal, and the sensitive issues concerning sovereignty over Jerusalem and access to the holy places. In the process, I hoped to achieve a permanent peace between the two countries based on full diplomatic recognition as would be confirmed by a bilateral peace treaty. Begin and Sadat were personally incompatible, and I decided after a few unpleasant encounters that they should not attempt to negotiate with each other. Instead, I worked during the last ten days and nights with each or with their representatives separately. Although this approach was more difficult for me -- I had to go from one negotiating session to another -- there were advantages in that it avoided the harsh rhetoric and personal arguing between the two leaders. At least with Begin, every word of the final agreement was carefully considered, and he and I spent a lot of time perusing a thesaurus and a dictionary. He was a careful semanticist. He surprised me once when I had proposed autonomy for the Palestinians; he insisted on "full autonomy." [1] Begin came to Camp David intending just to work out a statement of broad, general principles for a peace agreement, leaving to subordinates the task of resolving the more difficult details. It was soon obvious that he was more interested in discussing the Sinai than the West Bank and Gaza, and he spent the best part of his energy on the minute details of each proposal. The other key members of the Israeli team, Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan, Defense Minister Ezer Weizman, and Attorney General Aharon Barak, desired as full an agreement as possible with the Egyptians, and they were often able to convince Begin that a particular proposal was beneficial to Israel and would be approved by its citizens. Sadat wanted a comprehensive peace agreement, and he was the most forthcoming member of the Egyptian delegation. His general requirements were that all Israelis leave the Egyptian Sinai and that there be a comprehensive accord involving the occupied territories, Palestinian rights, and Israel's commitment to resolve peacefully any further disputes with its neighbors. Both sides would have to pledge to honor U.N. Resolution 242. Sadat usually left the details of the negotiations to me or the key negotiator of his Egyptian team, Osama el Baz. On several occasions either Begin or Sadat was ready to terminate the discussions and return home, but we finally negotiated the Camp David Accords (Appendix 3), including the framework of a peace treaty between the two nations (Appendix 4). The two leaders and their advisers even agreed upon my carefully worded paragraph on the most sensitive issue of all, the Holy City: Jerusalem, the city of peace, is holy to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and all peoples must have free access to it and enjoy the free exercise of worship and the right to visit and transit to the holy places without distinction or discrimination. The holy places of each faith will be under the administration and control of their representatives. A municipal council representative of the inhabitants of the city shall supervise essential functions in the city such as public utilities, public transportation, and tourism and shall ensure that each community can maintain its own cultural and educational institutions. At the last minute, however, after several days of unanimous agreement, both Sadat and Begin decided that there were already enough controversial elements in the Accords and requested that this paragraph be deleted from the final text. Map 4: Israel 1967-82 It is to be remembered that the Camp David Accords, signed by Sadat and Begin and officially ratified by both governments, reconfirmed a specific commitment to honor U.N. Resolutions 242 and 338, which prohibit acquisition of land by force and call for Israel's withdrawal from occupied territories. The Accords prescribe "full autonomy" for inhabitants of the occupied territories, withdrawal of Israeli military and civilian forces from the West Bank and Gaza, and the recognition of the Palestinian people as a separate political entity with a right to determine their own future, a major step toward a Palestinian state. They specify that Palestinians are to participate as equals in further negotiations, and the final status of the West Bank and Gaza is to be submitted "to a vote by the elected representatives of the inhabitants of the West Bank and Gaza." Furthermore, the Accords generally recognized that continuing to treat non- Jews in the occupied territories as a substratum of society is contrary to the principles of morality and justice on which democracies are founded. Begin and Sadat agreed that these apparently insurmountable problems concerning Palestinian rights would be overcome. In addition, the framework for an Egyptian-Israeli peace agreement was signed, calling for Israel's withdrawal from a demilitarized Sinai and the dismantling of settlements on Egyptian land, diplomatic relations between Israel and Egypt, borders open to trade and commerce, Israeli ships guaranteed passage through the Suez Canal, and a permanent peace treaty to confirm these agreements. Sadat always insisted that the first priority must be adherence to U.N. Resolution 242 and self-determination for the Palestinians, and everyone (perhaps excepting Begin) was convinced that these rights had been protected in the final document. All of us (including the prime minister) were also confident that the final terms of the treaty could be concluded within the three-month target time. Everyone knew that if Israel began building new settlements, the promise to grant the Palestinians "full autonomy," with an equal or final voice in determining the ultimate status of the occupied territories, would be violated. Perhaps the most serious omission of the Camp David talks was the failure to clarify in writing Begin's verbal promise concerning the settlement freeze during subsequent peace talks. One personal benefit to me from the long days of negotiation was a lifetime friendship with Ezer Weizman, who served as Israel's defense minister. More than any other member of Begin's team, I found Ezer eager to reach a comprehensive peace agreement, and he was a person with whom I could discuss very sensitive issues with frankness and confidence. He also had a good personal relationship with the Egyptians and would often go by Sadat's cabin for private discussions or a game of backgammon. These peace talks proved to be something of an epiphany for Weizman, who had been an early member of Begin's Irgun team of Zionist militants, a noted hero of the Six-Day War as director of the early morning strikes that decimated the Arab air forces, and a founder of the conservative Likud political party. He had been a leading "hawk" all his life but was converted during the weeks of negotiations into a strong proponent of reconciliation with the Arabs. [2] Our celebration of the Camp David Accords was short-lived, as we endured weeks of tedious and frustrating negotiations to implement our commitment to conclude a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. Six months after Camp David, I decided to go to Cairo and Jerusalem to try to resolve the remaining issues, and we were able to conclude the final terms of a definitive agreement. Although this crucial peace treaty has never been violated, other equally important provisions of our agreement have not been honored since I left office. The Israelis have never granted any appreciable autonomy to the Palestinians, and instead of withdrawing their military and political forces, Israeli leaders have tightened their hold on the occupied territories. Sadat withstood the condemnation of his fellow Arabs, who imposed severe though ultimately unsuccessful diplomatic, economic, and trade sanctions against Egypt in an attempt to isolate and punish him. Until much later, long after I left public office, neither the Jordanians nor the PLO were willing to participate in subsequent peace talks with Israel. This confirmed the Israelis' fears that their nation's existence would again be threatened as soon as their adversaries could accumulate enough strength to mount a military challenge. For Menachem Begin, the peace treaty with Egypt was the significant act for Israel, while solemn promises regarding the West Bank and Palestinians would be finessed or deliberately violated. With the bilateral treaty, Israel removed Egypt's considerable strength from the military equation of the Middle East and thus it permitted itself renewed freedom to pursue the goals of a fervent and dedicated minority of its citizens to confiscate, settle, and fortify the occupied territories. Israeli settlement activity still caused great con-cern, and in 1980, U.N. Resolution 465 (Appendix 5), calling on Israel to dismantle existing settlements in the Arab territories occupied since 1967, including East Jerusalem, was passed unanimously. We all knew that Israel must have a comprehensive and lasting peace, and this dream could have been realized if Is rael had complied with the Camp David Accords and refrained from colonizing the West Bank, with Arabs accepting Israel within its legal borders. ______________ Notes: 1. For a more complete day-by-day description of the Camp David negotiations, see Jimmy Carter, Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President (New York: Bantam, 1982), pp. 319-403; (repr. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1995), pp. 326-412. 2. Without my asking him, Ezer Weizman came to America during my re-election campaign in 1980 and visited several cities, publicly urging Jewish leaders to support my candidacy. Although strongly criticized for this unprecedented (and perhaps illegal) foreign involvement, he was undeterred.

|