|

THE CIA'S SECRET WAR IN TIBET -- HITTING THEIR STRIDE |

|

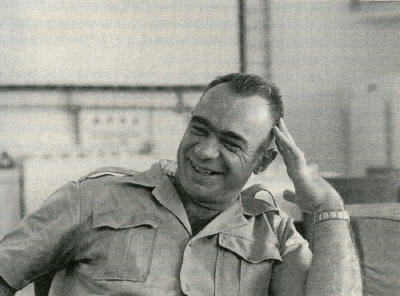

Chapter 9: Hitting Their Stride Nathan and his eight teammates hit the ground running -- literally. The C-130 had landed them nearly a day's march from the planned drop zone and dangerously close to a PLA encampment. Frightened of detection, they immediately fled toward their intended target without pausing to recover any supply bundles, including the radio. Over the ensuing days, their comedy of errors continued. Chancing upon some locals, Nathan learned that the resistance they sought had dispersed half a year earlier. Then when they tried to enter a village for refuge, the residents eyed their light complexions (the result of frequent classroom sessions over the previous ten months) and suspected them of being Chinese provocateurs. On the run from their own countrymen, the tired and hungry agents saw little choice but to avoid the thick PLA defenses sure to be found farther south near Lhasa and instead head west toward the Nepal border, some 500 kilometers away. [1] None of this was known to the CIA's planners, who were busy preparing for the next round of airborne infiltrations. Once again, they had to generate a list of potential drop zones without the benefit of current intelligence inside the country. One possibility had surfaced back in early June when the head of the Tibet Task Force, Roger MacCarthy, had ventured to Darjeeling to debrief NVDA chief Gompo Tashi. A former air force Morse operator, MacCarthy had begun his CIA career in 1952 when he answered an agency call for radio communicators. Known for his gregarious nature, he had been dispatched to Western Enterprises on Taiwan the following year and sufficiently impressed his superiors to qualify for junior officer training upon his Stateside return. Posted to Saipan after that, he was first exposed to the Tibet project while serving on the island as an instructor for the initial Khampa cadre in 1957. Deeply touched by their struggle, the thirty-two-year-old MacCarthy was quick to seize the opportunity to assume command of the Tibet Task Force from Frank Holober, who departed for an assignment in Japan just before the Dalai Lama's flight to exile in March 1959. Arriving in Darjeeling by way of Calcutta, MacCarthy was waiting inside a safe house when Gompo Tashi arrived in formal Western attire. He offered the Tibetan two cartons of Marlboros and two bottles of Scotch to break the ice. The general readily accepted the gifts and launched into a detailed diatribe about himself and his family's background. With Lhamo Tsering (who had recently returned from Camp Hale) providing translations, the Khampa leader spoke with sincerity and passion. "He showed me his scars from battle," said McCarthy, "and recited where they occurred like a road map." [2] Over the course of three days, the CIA officer and rebel leader reviewed details of the NVDA campaign to date. Gompo Tashi was honest about the resistance's shortcomings -- including bad behavior and defeats -- but overall, he thought the NVDA had done well. He was saddened, however, that he had not started organizing earlier. Apologizing for their poor guerrilla tactics, he noted his frustration in trying to convince other chieftains that a fifty-man point was excessive and could be seen from the air. In the end, Gompo Tashi had no ready answer about the future course of the resistance. Losses were costly, he conceded, and replacements were not readily available. Given the PLA's air capabilities, it was impossible to do much more than ambushes and interdiction of convoys and perhaps some sabotage. He was optimistic about running such missions from enclaves in Nepal, but more guarded about similar strikes staged out of NEFA. Gompo Tashi let something else slip as well. In his detailed recitation of NVDA activities, he recounted how he had operated with success along the westernmost edge of Kham in December 1958. Particularly around the town of Pembar, a supportive Khampa populace had allowed the resistance to keep the area free of Chinese. Though this information was dated, the location appealed to the CIA on another count: situated near the south bank of the Salween, Pembar was within striking distance of the drivable road the Chinese had constructed between Chamdo and Lhasa. Cutting traffic there would accomplish the same goals as the earlier stillborn effort, ST WHALE. Brainstorming further leads, the CIA came up with two other drop zone candidates. The first of these, deeper in Kham, was chosen in order to better exploit the ethnic background of most of the Hale students. Using the same logic, a third target was selected in southern Amdo in order to milk value from the three Amdowas in the contingent. To map out the exact routes to and from these locations, a U-2 overflight was sanctioned on 4 November to cover Tibet, China, and Burma. Roger MacCarthy, head of the Tibet Task Force. (Courtesy Roger MacCarthy) Back at Hale, the sixteen remaining graduates were briefed on their upcoming mission. Six would be dropped at Pembar, the CIA told them, five would land farther east in Kham, and another five would parachute inside Amdo. With the full moon falling at midmonth, the agents were rushed through Okinawa late in the second week of November on their way to Thailand. Escorting them this time was Zeke Zilaitis. Special permission had also been extended for Ray Stark to make the trip. Failure to contact the Nam Tso team, and a lingering suspicion that the agency's Thai-based communications officers might not have been sufficiently attentive to pick up a faint transmission out of Tibet, led Stark to vow to stay in Bangkok and personally "guarantee" to raise this latest group over the airwaves. Once at Takhli, the Tibetans waited until last light on the day before the full moon. At that point, they were then given an eleventh-hour change of plans: all three teams would jump at Pembar from a single plane, the CIA had decided, rather than using three separate drop zones; the Amdo and Kham teams would travel to their final destinations from Pembar on foot. This brightened the agents considerably, as they appreciated the psychological security of infiltrating as one. Waving good-bye to Zilaitis on the tarmac, they boarded a lone C-130 and disappeared toward the Burmese frontier. *** Inside the Hercules, twenty-one-year-old Donyo Pandatsang adjusted the cyanide ampoule encased in fine wire mesh that was strapped to his forearm. Answering to the name "Bruce" while at Hale, he had spoken no English when he arrived in Colorado but showed great natural aptitude and went on to advanced radio training. He was selected as team leader for the six men designated to remain at Pembar. Now lined up in front of the right cabin door, Bruce was petrified. "We had no idea about the fate of the Nam Tso team," he later recounted, "and none of us were natives of the Pembar area." But to his own surprise, as soon as he launched himself into the slipsteam, all fear vanished. With the sound of the plane fast receding, Bruce was overwhelmed by the prospect of being home. Dangling from the risers, he could clearly see that he was heading for a valley with snowcaps glistening on either side. His one complaint: "They told us we would land in a forest, but there was nothing but rocks." [3] Working in the moonlight, Bruce and his colleagues quickly located their supply pallets, including one that had to be fished from a river. Later that same night, they encountered locals from a small nearby village who had come to investigate the noise. Not only did the locals appear friendly, but they said that many Khampas were still living in the area. With this positive news, Bruce assembled his radio the following morning and tapped out a short message. His handlers at the Tibet Task Force now knew that the team was alive. *** Down in Bangkok, Ray Stark had taken up residence in the CIA's secure radio room inside the U.S. embassy. Though he had quiet confidence in the abilities of the agents he had trained, there was an element of anxiety about going out on a limb and guaranteeing contact. The anxiety did not last long. When Bruce's string of Morse came over the air the morning after infiltration, the local agency radiomen were shaking with excitement. "They could barely copy the message," recalled the elated instructor. His mission complete for the moment, Stark awarded himself two weeks' leave in Hong Kong and Tokyo on his way back to Colorado. *** It did not take long for word to spread around Pembar about the arrival of the CIA-trained cadre. As would-be guerrillas flocked to the scene, the agents knew that this rousing reception was a double-edged sword. Just as when Wangdu had landed in Kham in 1957, some of the Khampas came with no weapons; others came with an assortment of rifles but no bullets. Three different calibers of ammunition were in heavy demand, and expectations were high for the CIA to deliver. Back in Washington, the Tibet Task Force weighed the radioed requests for supplies. That a supportive public was itching to take up arms against the Chinese was a good thing, and much of the wish list emanating from Pembar (with the exception of pistol silencers) fell within reason. Approval was quickly secured for a single Hercules to be packed with pallets at Kadena and staged through Takhli during the next full moon in mid-December. Unlike the two earlier drops, the C-130's expansive rear ramp would be used instead of the smaller side doors; this would allow more supplies to be dispatched in less time. On the ground, the Tibetan agents had assembled a veritable fleet of mules at the designated drop zone. Six enormous dung bonfires were lit in an enormous "L" shape and, like clockwork, the C- 30 materialized overhead. Moments later, bundles hit earth. Inside each were stacks of cardboard boxes with four rifles apiece. As per their training at Hale, the agents had affixed ropes to the mule saddles, allowing two boxes to be quickly secured to each animal. Within two hours, the entire drop zone had been cleared. Nearly all the 200-plus Garand rifles were distributed to local guerrilla volunteers. Fifty rifles, however, were earmarked for a band of Khampas selected to escort the five agents destined to shift from Pembar to Amdo. As planned, those five crossed the Salween at year's end and proceeded 150 kilometers northwest. Still 80 kilometers short of Amdo's Jyekundo district, the team came upon a fertile resistance presence and decided to go no further. With this second guerrilla network running by the start of 1959, at long last the task force was beginning to hit its stride. *** On the diplomatic front, too, the struggle for Tibet was heating up. Back on 23 April, the Dalai Lama had sent his oral message to the U.S. government through Gyalo Thondup, reaffirming his determination to support the resistance of his people. He made two requests of Washington at that time: recognize his soon-to-be-formed government in exile, and continue to supply the resistance. He reiterated these themes in a formal scroll, a summary of which reached the White House by 16 June. In this, the Dalai Lama further suggested that Tibetan independence be a prerequisite for Beijing's entry into the United Nations. Pressed to compose an answer, the Department of State begged caution. The Dalai Lama should not publicly ask for recognition of a government in exile, urged one Foggy Bottom draft, unless he was assured of a warm international response. If he made an appeal to the United Nations, State Department policy makers felt that the United States should appropriately assist; if not, the United States should not take the lead in pressing Tibet's case in the international arena. And taking a page from sweeteners offered earlier in the decade, they believed that the United States should offer a stipend and help the Dalai Lama find asylum elsewhere if India gave him the boot. Eisenhower was of a mind to agree with such circular diplomatic niceties. When a final response was orally relayed back to the monarch on 18 June, it mouthed sympathy for the Tibetan cause with few commitments. Addressing the Dalai Lama as the "rightful leader of the Tibetan people," it even managed to dance around the earlier semantics surrounding suzerainty, sovereignty, and independence. Not surprisingly, word quickly came back that neither the Dalai Lama nor Gyalo Thondup was pleased with Washington's limp platitudes. The monarch was especially keen to elicit stronger U.S. support, given his growing strains with Nehru (the Indian leader was insistent that the Dalai Lama work quietly for autonomy, while the Tibetan leader spent the summer threatening to make a bold declaration of independence), and Washington's less than full assurances did nothing to bolster his leverage with New Delhi. Perhaps the only good news, from the Tibetan perspective, was the U.S. government's willingness to act as a background cheerleader for Tibet's case at the United Nations. This gained momentum on 25 July, when the International Commission of Jurists published a 208-page preliminary report entitled "The Question of Tibet and the Rule of Law." Distributed to the United Nations Secretariat and all delegations, it laid the basis for the Tibet issue to be included on the agenda for that fall's United Nations session. Seizing this opportunity, Gyalo Thondup hired Ernest Gross, a former State Department legal adviser and alternate delegate to three United Nations General Assemblies, to represent Tibet. Unlike Lhasa's earlier flirtations with the United Nations -- when it was roundly ignored at the beginning of the decade -- this time the experienced Gross proved an adept lobbyist. With co-sponsorship from Ireland and Malaya, a Tibet resolution was scheduled for a hearing in front of the full assembly during mid-October. Behind the scenes, the Tibet Task Force crafted several covert efforts to support the upcoming vote. In one of these, Lowell Thomas, Jr., who had traveled with his famous father through Tibet in 1949 and become an impassioned advocate of Tibetan independence, was fed intelligence supplied by CIA guerrilla contacts. Some of this information was incorporated into his highly sympathetic book The Silent War in Tibet, published by Doubleday on 8 October. Later that same week, the 12 October edition of Life International included an article entitled "Asia's Odd New Battlegrounds." In it were six drawings, ostensibly made by "refugees," graphically depicting Chinese excesses against Tibet. Left unsaid was the fact that the drawings had actually been made by the agent trainees at Camp Hale as part of sketching drills during a class on intelligence collection. The best of these drawings had been presented by the Hale staff to Des FitzGerald, who took them to CIA Director Dulles, who in turn phoned C. D. Jackson, the conservative Life International publisher (and former member of the Eisenhower election campaign), with a request that they be incorporated in a supportive article. [4] All this culminated in passage of a United Nations resolution on 21 October deploring China's violations of human rights in Tibet. The vote was forty-five in favor, nine opposed, and twenty-six abstentions. Besides the numeric victory, there were other reasons for cheer. Though short of the declaration of independence wanted by the Dalai Lama, the vote served to keep the Tibetan case alive before the international community. Moreover, the experience had proved invaluable for Gyalo Thondup. Far from the uninspiring introvert witnessed by earlier case officers in India, a far more confident and dynamic Gyalo had emerged at the United Nations. Gyalo could be stubborn as well. Not willing to lose momentum after the resolution, Gross immediately formulated plans for the first overseas trip by the Dalai Lama. Using the same lobbying skills that had been successful in the halls of the United Nations, he persuaded the National Council of Christians and Jews to call a conference for the spring of 1960 with the Dalai Lama as principal speaker. The venue would be the Peter Cooper Union in New York, followed by an unofficial reception hosted by Eisenhower in Washington. All that remained was a pledge of cooperation from Gyalo and the Dalai Lama. To the shock of U.S. officials, however, both opposed the trip because it would set a precedent for an unofficial reception in the Dalai Lama's capacity as a religious leader. Though by late 1959 the monarch had temporarily shelved plans to set up a government in exile (because of ongoing opposition from India), he refused to prejudice future claims to independence in return for what he deemed was a short-term advantage. On the diplomatic front, at least, this prime opportunity ultimately wafted away. *** For the agents back in Tibet, the task force was taking steps to ratchet up its resupply operations. Through December 1959, these flights had been limited to one Air America aircrew flying a single mission during each full moon phase. Since the lunar window of opportunity could not be expanded, the only other option was to increase the number of sorties flown. In anticipation of this, Air America in early December allocated additional personnel for C-130 operations. In several cases, some of its more experienced pilots were brought into the program to serve functions other than flying the plane. Captains Ron Sutphin and Harry Hudson, for example, were given quick code training in Japan before being assigned as radio operators; another pilot, Jack Stilts, was named a flight mechanic. [5] More C-130 flights also meant the need for more kickers. Efforts to secure these personnel began in November 1959 when two Montana smoke jumpers -- Miles Johnson and John Lewis -- were beckoned to Washington for background security checks. John Greaney, the task force officer who had first scouted Camp Hale, reserved rooms under false names at the Roger Smith Hotel in order to conduct confidential interviews with the prospects. The following month, half a dozen more smoke jumpers were invited to the capital. Shep Johnson, Miles's younger brother, was among them. A former marine and Korean War veteran, he had been tending cattle at a snowy Idaho ranch when he got an urgent message to come to the phone. "I thought my mother was sick," he recalls, "but it was another smoke jumper saying that I was needed in Washington. The next day I bought a sports coat and flew to D.C., where I met some of the CIA officers, including Gar [Thorsrud]. We spent ten days looking over maps. Then they gave me an advance in pay; it was the first time I had handled a $100 bill." [6] By the full moon cycle of January 1960, nearly a dozen smoke jumpers were assembled on Okinawa. Four kickers were selected to go on that month's maiden flight: two from the new contingent, and two veterans from earlier flights. The mission took place as scheduled and without complications, prompting the ST BARNUM planners to reduce the number of kickers to two for the month's second resupply flight. During this encore, a single Tibetan agent was scheduled to jump along with the supplies. That agent, a reserved twenty-eight-year-old Khampa monk named Kalden, had been one of the washouts from the Lithang contingent that had parachuted at Nam Tso. Kalden had been sitting idle at the Kadena safe house for the past sixteen months while the CIA debated what to do with him. That decision: drop him at Pembar. As the Hercules made its final approach toward the drop zone, radioman Keck and flight mechanic Stiles came into the cabin to help push pallets out the rear. One of the two kickers, Andy Andersen, was positioned close to the edge of the ramp alongside the lone Tibetan. Not secured by a tether, Andersen instead wore a special small parachute set high on the shoulder to keep the waist clear and eliminate the possibility of getting snagged while pushing the cargo. [7] When the green light went on, Kalden got a tap on his shoulder as the signal to leap off the ramp. For the first time, a Tibetan balked. Turning his back on the black void, the monk grabbed Andersen in an unwelcome embrace. All too aware of his precarious position, the kicker spun the agent around and heaved him ahead of the exiting cargo. Reaching backward in a final act of desperation, the Tibetan snatched the radio headset off Andersen's head. Trailing a thirty-foot cord in hand, he disappeared into the night sky. [8] Down at the drop zone, Kalden landed to a reception committee of eleven fellow agents and hundreds of Khampa guerrillas. He came with orders to join the five agents meant to shift farther east into Kham, though plans for that movement were now on hold. Remaining at Pembar, the twelve took stock of their growing inventory. Included in the pallets were a pair of machine guns on anti-aircraft mounts and a large stock of TNT. None of these items were rated as particularly relevant by the Tibetans, though they did go out of their way to use the explosives to down a nearby bridge. More popular were the hundreds of Garands and a carbine variant stacked inside the bundles, both of which were magnets for new recruits. Sensing that it had arrived at a winning formula, the Tibet Task Force planned more of the same for February 1960. Helping to coordinate the ongoing resupply effort from Kadena was U.S. Air Force Major Harry "Heinie" Aderholt. No stranger to the CIA, Aderholt had been seconded to Camp Peary for three years starting in 1951 to help set up an air branch at the agency's new training facility. After a six-year interlude with the Tactical Air Command beginning in 1954, he was again detailed to the CIA in January 1960, this time as commander of the Kadena-based Detachment 2, 1045th Operational Evaluation and Training Group. Aderholt's Detachment 2 had a long and convoluted relationship with the Tibet project. Its lineage could be traced back to the long-disbanded Asia-based ARC wing, a portion of which had been retained as the 322nd Squadron's Detachment 1. When that squadron was dissolved in late 1957, its secret cell (renamed Detachment 2 of the 313th Air Division) remained at Kadena and continued to receive orders for CIA-sanctioned flights, such as the C-118 personnel ex filtrations from Kurmitola. Its C-118 was also loaned for CAT-piloted flights into Tibet.

By the time Aderholt arrived, there had been two significant changes to the detachment. First, whereas the earlier arrangement had been a partnership between the agency and the air force, the CIA now fully controlled Detachment 2 in all but name. The agency went so far as to remove the Kadena unit from the 313th Air Division and place it under its own cover organization, the 1045th Operational Evaluation and Training Group, ostensibly headquartered at Washington's Bolling Field. Second, Detachment 2 was no longer in the business of flying classified flights on behalf of the CIA. Rather, it now acted as the CIA's on-site management team to coordinate Air America and U.S. Air Force assets and personnel in support of the agency's cold war ventures in Asia. Aderholt tackled his new assignment with breathless vigor and initiated several fast changes. His immediate predecessor in command of the detachment, Major Arthur Dittrich, was a longtime CIA hand in Asia, having helped coordinate covert flights into mainland China during the Korean War. But whereas Dittrich had preferred to err on the side of caution and limit C-130 payloads to 13,500 pounds, Aderholt elected to push the envelope by packing up to 26,000 pounds of cargo per ship. Aderholt also took steps to upgrade the primitive conditions at Takhli Air Base. Where once only native huts had stood, he cleared out the old imperial Japanese living areas and erected new elevated quarters. This move was warmly welcomed by the Air America crews, who had taken to heart Takhli's reputed claim of being home to more king cobras than anywhere else on the planet. By the March full moon, the C-130 crews had amassed sufficient Tibet experience to begin staging two aircraft per night. There was the occasional gaffe -- such as when Captain Harry Hudson accidentally left his survival belt atop a pallet, resulting in a costly loss when the gold sovereigns inside went out the rear -- and periodic bouts with Murphy's Law -- such as the frequent glitches with the aircraft's temperamental radar, forcing the navigator to rely on celestial fixes. But ST BARNUM was generally running on schedule. [9] The news got even better when the Nam Tso team -- on the run since September 1959 -- reached the Nepalese border and couriered word to Darjeeling that it wanted a resupply. Lhamo Tsering, who had been deputized by Gyalo Thondup to manage agent operations from India on a daily basis, quickly relayed the request to the Tibet Task Force. Rejecting the plea, the CIA instead ordered the team to ex filtrate via East Pakistan to Okinawa. Re-armed with carbines and recoilless rifles, Nathan and six of his men (due to failing physical health, the two older agents remained behind at Kadena) were loaded back aboard a Hercules and dropped during the March full moon to augment the five-man Amdo team that had shifted from Pembar. [10] Not until the next month, April, did the CIA's luck finally run out. It started out well enough, with two Hercules flights set for the beginning of the lunar cycle. The first plane, with Doc Johnson as pilot and Jack Stiles serving as first officer, departed without incident at last light. The second, teaming William Welk and Al Judkins, left Takhli fifteen minutes later. Halfway to the target, things turned sour. Hitting an unexpectedly heavy head wind, Jim Keck, one of two navigators in the lead plane, took a radar fix and determined that they were more than forty-five minutes behind schedule. Hearing this, Doc Johnson added power, and by the time they approached the drop zone, they were only four minutes late. Head winds, however, were just part of their problem. Although April is traditionally rain free in Tibet, 1960 proved the exception to the rule. As the Hercules overflew the location where bonfires should have been, all the crew saw was a thick blanket of clouds. Circling once in frustration, Johnson made the decision to return home. As they had burned an inordinate amount of fuel to make up for lost time on the way into Tibet, his colleagues in the cockpit were keen to dump their cargo to lighten the plane for the remainder of the journey. But reasoning that the same strong head winds would provide equally strong tailwinds, Johnson insisted on keeping the payload aboard. That decision was nearly fatal. By the time they arrived near Takhli at 5: 30 the next morning, their fuel supply was almost exhausted. Worse, April is the hottest month in Thailand, coming less than two months before the summer monsoon, and farmers in the central part of the kingdom traditionally slash and burn their fields then, prior to planting a new crop. This throws into the sky a layer of haze the color and consistency of chocolate milk, which is exactly what the crew saw as they searched frantically for the lights of Takhli. Jack Stiles, who was taking his turn at the controls for the return leg, put the plane into a tight turn for a second pass. Two of the engines immediately begin to sputter, then coughed back to life as the Hercules rolled out. The engines started to die again during a third pass, prompting Stiles to order crew members in the rear to put on their parachutes and bailout. "It was probably not a bad idea," said Andy Andersen, one of two kickers on the flight, "but none of us moved." [11] Listening from the tarmac, Heinie Aderholt acted in desperation. Locating a flare gun, he began firing red star clusters into the sky. The idea worked: spotting a red glow lighting the bottom of the haze, the crew took the plunge and emerged in clear skies near the airfield. Only one engine was still running by the time they taxied to the end of the runway. "My jaw was sore," remembers navigator Keck, "from all the sticks of gum I was chewing." [12] Hard luck, too, plagued the second flight of the night. Captain elk also hit a head wind and found the drop zone covered with clouds. Like Doc Johnson, he elected to return with his payload aboard. Unlike Johnson, however, he believed that the emergency facilities at Kurmitola were closer. The CIA retained a skeleton technical crew in East Pakistan for just such contingencies and had even erected a non directional beacon to help pilots vector toward the strip. Normally, this would have been sufficient, since April in East Pakistan is generally a month with humid temperatures but clear skies. But in yet another exception to the rule, Kurmitola that night was hit by an unseasonably early thunderstorm. Al Judkins was at the controls, and as he dipped the Hercules for a landing, there was almost zero visibility. At the last moment, the hangar flashed in the windshield, prompting Judkins to reflexively jerk back on the controls to avoid a collision. Doing what it could to help, the CIA team rushed several jeeps out onto the tarmac, their headlights barely cutting into the pounding rain. As Judkins nosed downward for a second attempt, kickers Miles Johnson and Richard "Paper Legs" Peterson braced for the worst. After a night of jinxes, they finally got a break. As a bolt of lightning flashed across the sky, the crew got a clear glimpse of the airstrip ahead and aligned the plane. Landing hard, they taxied to the hangar with little more than fumes left in the gas tanks. [13] Though it had nearly lost two aircraft, ST BARNUM barely flinched. On the following night, the same Takhli crew was rescheduled to deliver its payload. Fearful of running into the same meteorological complications, the airmen brainstormed ways of carrying more fuel as an emergency reserve. Besides the internal wing tanks, they were already slinging two extra pontoon tanks, as well as a special 2,000-gallon bladder -- nicknamed a Tokyo Tank -- inside the cabin itself. But even with these, the crew could not fly an evasive route to the target, could not loiter, and, as the previous flights had dramatically proved, could not afford to hit a strong head wind. Showing some lateral thinking, they came up with an offbeat solution. Reasoning that fuel is denser when chilled, the Air America crew topped its tanks on the night of the mission and circled Takhli at 9,091 meters (30,000) feet. After determining that the gas was sufficiently cold -- and dense -- they landed and began packing more fuel into the extra tank space. Wet burlap was draped across the wings to keep the tanks cool. Whether because of this or because the crew did not encounter another head wind, the mission made it to Tibet and back with fuel to spare. [14] *** A key link in the CIA's Tibet supply program was a modest apartment just north of the Washington city limits. By that time, Geshe Wangyal had raised too many eyebrows roaming outside the original Zebra safe house in his robes. "He would go into a Chinese restaurant," recalls Tom Fosmire, "and the staff would all start bowing." [15] To avoid uncomfortable questions from neighbors, the CIA elected to shift its elegant interpreter to a new safe house farther outside the capital. Shortly thereafter, the venerable Geshe, eager to spend more time with his Buddhist disciples, gracefully exited the program for a permanent return to New Jersey. Though sad to see him go, the CIA had already located a willing replacement. Tsing-po Yu, a recent Chinese immigrant who had lived part of his life in Tibet and spoke the language like a native, began daily commutes to the new safe house and proved adept at squeezing meaning from the Tibet transmissions. The CIA, in turn, provided him with a salary and an occasional favor. When his wife, a waitress at a local Chinese eatery, was being seduced by a cook, the agency arranged for immigration officials to raid the establishment and deport seven illegal employees (including the problematic suitor). [16] Because of his marital troubles and the long hours spent translating, Yu had been granted leave during April when the two Tibet overflights had their brushes with disaster. Filling in as his temporary replacement was Mark, one of the three Tibetans serving as translators at Hale. Alongside Mark was case officer John Gilhooley. Having recently come off a tour in Burma, Gilhooley was holding the headquarters job with the Tibet Task Force between field assignments. Each morning, the young Tibetan would begin the process of converting incoming number groups into coherent messages, which Gilhooley would then convey to task force chief Roger McCarthy. Return messages would go through the same process in reverse. Mark enjoyed the work but could feel the growing sense of urgency among all those involved. There was good reason for this: the approaching May rains on the Tibetan plateau would make further resupply flights all but impossible until autumn. In order to deliver as much equipment as possible before the weather proved prohibitive, three C-130 flights were launched on two consecutive nights at the end of the April lunar cycle. [17] In the end, even this proved insufficient. Over the previous two months, Pembar had been experiencing frequent probes by PLA infantry. Just as the April full moon was waning, Beijing got serious. Pamphlets were dropped from aircraft warning the rebels to cease contact with the foreign reactionaries. After that, groups of five aircraft began bombing runs while long-range artillery was brought forward. The guerrillas -- conservatively estimated at a couple of thousand -- suffered horrific casualties. The PLA was not finished. Placing blocking forces on three sides of the guerrilla concentration, the Chinese set the forests on fire to flush out the remaining partisans. Keeping together, the twelve CIA-trained agents made an escape bid. Rather than running south toward India -- as the PLA might have expected -- they attempted to evade north across the Salween. "We thought it might be colder near Amdo," said Bruce, "and the Chinese would not be able to tolerate the cold." [18] But as they approached the river, its swift waters proved too hard to ford. Complicating matters, their horses were growing weak from insufficient food and were hobbled by broken horseshoes. Abandoning their steeds, the dozen decided to reverse direction and weave their way toward the southern border on foot. After a month of harrowing encounters with the PLA, only five survivors reached Indian soil. [19] The losses were even more horrific for the Amdo contingent. After overrunning Pembar, the PLA shifted its full attention northwest near the end of April. Under withering fire, Nathan, leader of the Amdo augmentation team, radioed frantic messages that tank-led columns were closing on their position. [20] With few options available, the Tibet Task Force sanctioned an emergency C-130 drop for the evening of 1 May. This promised to be doubly risky: not only was the PLA massing in the area around the drop zone, but the moonless night would make navigation much more complicated. Captain Neese Hicks, who had been given a quick tutorial in codes before being assigned as a radioman for the project, was ready to board the Hercules at last light. Before he could do so, Major Aderholt rushed over to the crew and told them that the mission was scrubbed. [21] Aderholt did not elaborate, but the reason for the abort was a mishap in another CIA operation. That morning, a U-2 spy plane had departed from an airfield in Pakistan for an overflight of the Soviet Union. En route, Soviet air defense batteries had fired multiple surface-to-air missiles in a shotgun configuration, disabling the aircraft with one of the concussion blasts. Although the exact fate of the plane and its pilot was not yet known to the CIA (it was several days before Moscow revealed that the crewman, Francis Gary Powers, had been captured alive), Washington quickly flashed a blanket prohibition against all further aerial penetrations of the communist bloc. [22] With its hands tied by the senior policy makers in the Eisenhower administration, the Tibet Task Force was powerless to help its Tibetans in their greatest hour of need. The radio near Amdo soon fell silent. None of the twelve agents ever reached India. [23]

|

|