|

THE CIA'S SECRET WAR IN TIBET -- MARKHAM |

|

Chapter 10: Markham Back on 4 February, just as the Tibet Task Force thought it had settled on a winning formula, CIA Director Dulles ventured to the White House to brief top administration officials on the agency's Tibet operation to date. He closed with an appeal for continuation of the project. His audience was complicit in its silence, with only President Eisenhower wondering aloud if the net results merited the effort involved. Might not stoking the resistance, he posed, only invite greater Chinese repression? Des FitzGerald, who had joined Dulles for the briefing, spoke directly to the president's concern. There could be no greater brutality, he assured those at the table, than that already inflicted on the Tibetans. [1] Still playing devil's advocate, Eisenhower turned to Secretary of State Christian Herter and asked if his department held any reservations. Far from it, responded Herter. Not only could the Tibetans offer" serious harassment" of the Chinese, but a successful resistance would keep "the spark alive in the entire area." Suitably convinced, Eisenhower granted his consent for continuation of the Tibet operation. [2] *** Hale had changed little over the previous year of training. Still in charge was Tom Fosmire. Zeke Zilaitis, back to experimenting with rockets, had been promoted to his deputy. Gil Strickler, Patton's former logistician, made irregular visits to assist with support from Fort Carson. In the field, Tony Poe and Billy Smith remained as tactical instructors. Joining them was Don Cesare, a former marine captain with a taste for chewing tobacco. This was not Cesare's debut with the agency; he had previously served as a security officer for the U-2 spy plane program. [4] Other new faces included Joe Slavin and William Toler, two active-duty cooks seconded from the U.S. Army. They were warmly welcomed not only for their culinary talents but also for the fact that they freed the CIA officers from kitchen duties. A third newcomer, Harry Gordon, doubled as both project physician and medical instructor for select Tibetan students. Making the occasional appearance was another of Roger McCarthy's logistical assistants on the Tibet Task Force, Harry Archer. A Virginia Military Institute graduate from a moneyed family, Archer had entered the Marine Corps in 1953 for a two-year stint. After switching to the CIA, he served an initial tour on Saipan with McCarthy. The two again came together on the Tibet project, where Archer earned a reputation as a "gadget man." "Harry would go to Abercrombie & Fitch," said fellow task force member John Greaney, referring to the exclusive Manhattan outlet for pricey camping equipment, "and procure the latest in cold- weather gear, knives, and boots." Not all the purchases were appropriate. "He got us a bunch of thumb saws," recalls Fosmire, "even though there was no wood near most of our Tibet drop zones." Given his marine background, it was Archer who lobbied for the Tibetans to be rotated from Hale to the Marine Corps School at Quantico, Virginia, for a change of pace. There was sound logic behind Archer's proposal: Quantico at the time had a special cell that trained various foreign groups in guerrilla warfare and small-unit tactics. The school also had a pack-mule course where the marine instructors could teach slinging a 75mm recoilless rifle, one of the more cumbersome weapons being dropped inside Tibet. [5] Escorted by McCarthy, an initial group of twelve Tibetans was flown directly to the airstrip at Quantico in early 1960. There a five-man marine team -- which was not privy to the students' nationality -- put them through two weeks of instruction on everything from caches to camouflage. Mark and Pete were on hand to provide translations. Near the end of the cycle, the marines planned an elaborate ambush exercise in which they would play the part of aggressors. On the night before the drill was to start, however, six inches of snow hit northern Virginia. Improvising, the aggressors grabbed white bed sheets and threw them over their ambush position. "The exercise went off perfectly," said Sergeant Willard "Sam" Poss, "and we were able to show the students the need for versatility." [6] Impressed by the training at Quantico, McCarthy sent a request up the chain of command for the loan of two instructors. The Marine Corps was agreeable, releasing both Poss and Staff Sergeant Robert Laber that spring for temporary duty in Colorado. A Korean War veteran, Laber had been involved in the final combat actions of that conflict; he had since served as a heavy machine gun instructor before joining Quantico's special training cell. Training officer Sam Poss stands over the burned wreck of the

administration building Upon their arrival at Hale, the two marines were in awe of the base's diverse mini-armory, comprising both Western and communist bloc weaponry. "We were to teach the Tibetans how to use these and maneuver in a combat situation," said Poss. "This meant overcoming their first instinct, which was to stand in a line and fire everything they had until their bullets were finished, then pick up some rocks." [7] Initially, Poss focused on map reading. Since the Tibetans were weak in mathematics, special maps were adapted from dated World Airway charts. Printed on cloth, they were simplified for the Tibetans by making both magnetic north and true north the same. Laber, meanwhile, spent his time at the rifle range. As both a former machine gun instructor and a mortar section leader, he focused on developing skills with both these weapons. Because Fosmire and Zilaitis insisted on keeping the training as authentic as possible, blanks were never used. This resulted in an embarrassing breach of security midway through the dry summer. As Laber watched the Tibetans blaze away one afternoon with white phosphorus rounds, one ricocheted into the tress. In minutes, an entire hillside was in flames. The CIA staff was now in a quandary. They could not cope with the fire themselves, but inviting the Forest Service into the camp could expose the project. There was really no choice. The Tibetans were rushed back to their quarters and quarantined before the gates were opened to allow in the fire trucks. It eventually took an entire week to bring the blaze under control. The firefighters were instructed not to ask too many questions, though they did remark that "strange inscriptions" in a foreign language had been carved into some rocks. [8] That incident aside, the Tibetans made good progress through late summer. Groups of students were taken for overnight forays into the hills with the tactical instructors, where they would call in mountaintop resupply drops -- including a leaflet printing press developed by the task force's resident scholar, Ken Knaus -- and radio regular updates back to Ray Stark at base. And after word got back that the Amdo contingent had been overrun with tanks, an old Sherman was donated by Fort Carson for the students to practice both driving and disabling. [9] As graduation approached, the Tibetans were scheduled to showcase their skills to a headquarters delegation led by Des FitzGerald. Joining him was Gyalo Thondup, who was in the United States for what was becoming an annual tour for consultations and to bolster international support at the United Nations. The Hale staff had assembled some stands for their guests and spent days rehearsing their demonstration. Recalls Fosmire: "It ended with a mad minute attack on a 'Chinese' camp. All of the weapons were used, even mortars. One camouflaged Tibetan with a Bren was hiding near the reviewing stand and surprised everyone. When the last mortar round landed, they looted the camp." FitzGerald was delighted with the performance of what was widely recognized as his favorite project. Given his own wartime experience in Burma, he took the opportunity to quiz the Hale staff. "He was particularly interested and impressed with our cache training," remembers Cesare. [10] Although FitzGerald might have been deeply committed to it, trouble loomed for the Tibet project. For one thing, all the airborne teams operating inside Tibet during the first quarter of 1960 were wiped out by late spring; sending more agents according to the same script no longer seemed an enlightened idea. For another thing, the Eisenhower administration was dragging its feet on lifting the prohibition against overflights put in place after the downing of the U-2 in May. Not only was Eisenhower still smarting from the diplomatic fallout from that incident, but Washington was now backdrop to a tight presidential race between Vice President Richard Nixon and Democratic Senator John Kennedy. Political prudence dictated that potentially embarrassing covert action -- particularly overflights -- be put on hold until after the November election. [11] The delay came at a bad time for the Tibet Task Force. The late fall was good parachuting weather over Tibet. Moreover, there was concern that morale among the Tibetans at Hale might fray if they got stranded for an extended period. To keep them occupied, U.S. Army engineers were dispatched to build a gymnasium alongside their Quonset huts. The CIA also procured reels of television westerns and showed them every night. A favorite was Cheyenne, then still in the midst of its eight-year run with the hulking Clint Walker in the title role of an adventurer roaming the post-Civil War West. Said Cesare, "The Tibetans even began imitatingWalker's mannerisms around camp." [12] The CIA instructors, too, were growing bored with the tedious weeks of waiting. Billy Smith had already taken an opportunity for reassignment. A gruff Tony Poe, who was losing patience with some of his fellow officers, and disappointed that many of the Tibetans had taken up the habit of cigarette smoking, left near year's end. The two marines also made plans for a return to Quantico. [13] But the biggest blow came when Tom Fosmire elected to join McCarthy back at the task force desk in Washington. As the figurative heart of the training project since its inception, he had connected with the Tibetans more than any other CIA officer. Much of this had come about while sitting around the campfire at night swapping tales and bonding with his students. He recalls: "The Tibetans talked about going on annual trade caravans into India. There was much competition to be the first caravan of the season, because their goods were in highest demand and they made the most money. This meant surviving things like avalanches and bandits. They told me that once Tibet was free, they were going to take me on the biggest caravan ever into Lhasa." On the night before Fosmire was set to leave, he assembled all the Tibetans and made the announcement. Instantly, tears began to flow. Even when he tried to assure them that he would be working on the program from Washington, it did no good. "We were all crying like babies," said translator Mark. Choked with emotion, Fosmire took a twenty-minute walk to clear his head. "We made a note never to tell them again when one of us was leaving." [14] *** With morale already low following Fosmire's departure, the project took another hit in early November. By one of the closest margins in recent presidential history, John Kennedy came out the winner. Although he had been given a pair of confidential CIA briefings by CIA Director Dulles prior to the election, Tibet had not been broached with the youthful nominee. "I'll brief Nixon," Eisenhower was rumored to have told top agency officials regarding Tibet, "but if the other guy wins, you've got to do it." [15] When Dulles again got a chance to speak with President-Elect Kennedy on 18 November, ten days after the vote, Tibet was penciled on the agenda, but it never came up in conversation. Instead, the showdown with Cuba, and the agency's plans to launch an invasion of that island, dominated their talk. Even after Kennedy was inaugurated in early January 1961, other foreign policy items grabbed the early spotlight. Besides Cuba, the deteriorating situations in Laos and South Vietnam were making headlines, relegating Tibet far down the priorities list. Not until a snowy day in mid-February did things begin to change. Fosmire, who had been minding the quiet Tibet desk through the winter, remembers: "Bill Broe, the deputy chief of the Far East Division, stormed into the office with ice in his hair. He took off his jacket and waved a slip of paper. It was our permission to resume." [16] That permission followed from a 14 February decision by Kennedy's top foreign policy advisers -- his so-called Special Group -- to continue the covert Tibet operation started under the previous administration. [17] It had been almost a year since the last agent drop. With clear skies over Tibet, the task force moved to seize the moment. Even though the earlier airborne teams had met with only limited success -- and the concept of blind drops had been a complete bust during other agency operations in places such as China, Albania, and Ukraine -- plans were drawn up for yet another parachute infiltration. [18] The CIA's Tibet officers had reason to ignore their poor airborne track record and opt for the same tired formula. One of its agent trainees at Hale, a young Khampa named Yeshi Wangyal, was easily among the most capable Tibetans to pass through its gates. Known as "Tim" during his tenure in Colorado, he hailed from the town of Markham. Located between the Mekong and Yangtze Rivers, Markham had repeatedly attracted attention during years past. Early in the twentieth century, it had been the scene of seesaw battles as Chinese and Tibetan armies wrestled for control of Kham, with the Han more often than not coming up short. Markham had still been under Lhasa's sphere of influence in 1950, but it fell as one of the initial targets of the PLA invasion. This did little to extinguish the zeal of the town's residents. Although the Kham of neighboring Lithang may have headlined the top ranks of the Chushi Gangdruk resistance when it formed in 1956, sons of Markham were among the budding rebellion's other prominent partisans. [19] The Kham region showing the extent of Chinese highway construction, circa 1960 Markham was significant on other counts. For one thing, it sat at the terminus of a second drivable road the Chinese were building across Kham, and the CIA remained committed to disrupting Beijing's logistical flow. For another thing, not only were guerrillas around Markham still confounding the Chinese as of late 1960 (according to reports reaching India), but one of the rebel chieftains was none other than Tim's father. Therefore, parachuting Tim back into his hometown would not exactly be a blind drop. To increase Tim's chances of success, he was allowed to pick his own team-mates from among the candidates at Hale. Selected as deputy team leader was Bhusang, a thirty-two-year-old former medical student from Lhasa who went by the call sign "Ken." Five others -- Aaron, Collin, Duke, Luke, and Phillip -- also made the cut. [20] During the last week of March 1961, the seven began their long return journey from Colorado. Escorting them was translator Mark and CIA officer Zilaitis, who had been promoted to training chief following Fosmire's departure. After a three-night delay at Takhli due to unseasonably bad weather, the team boarded a C-130A as the sun set on 31 March. [21] Mark, who was the same age as Tim and had grown close to him during training, was bawling on the tarmac. Tim, his voice choked, passed on a request for Lhamo Tsering to take care of his young bride. [22] Inside the cockpit, the Air America crew refamiliarized themselves with the controls. It had been nearly a year since they flew the last Hercules drop, and the company had few aviators to spare, given its busy flying schedule for the rapidly expanding CIA operation in nearby Laos. Smoke jumpers, too, were at a premium, with only Miles Johnson and Paper Legs Peterson assigned to Asia in early 1961; all their fellow smoke jumpers-cum-kickers were in Latin America working on the imminent CIA paramilitary invasion of Cuba. [23] Roaring down the runway, the aircraft rose slowly on its journey toward Kham. At 2300 hours, under a full moon, the green light flashed in the cabin. Seven men and cargo exited the side doors. The battle for Markham was about to heat up. *** Assembling on the ground undetected, the agents had no problem locating their supplies. Though this might have been cause for celebration, Tim was far from happy. Landing among rocks, one of his teammates, Aaron, was cringing in pain with a dislocated shoulder. Worse, by sunrise he made the unwelcome discovery that the Hercules had significantly overshot the intended drop zone. Their current position, he calculated, was due west of the town of Gonjo. Like Markham, numerous skirmishes had been fought around Gonjo during the first half of the twentieth century as the Chinese and Tibetans vied for control. The difference, Tim noted with concern, was that Gonjo was more than 100 kilometers north of his hometown. Resting through the afternoon of the second day, the team prepared for the long walk south. Given Aaron's shoulder, their supplies were divided among the six healthy members. The remaining evidence of their drop -- parachutes and rigging materials -- was placed atop a pyre of wood and brush. They struck a match to the tinder and then set off at dusk up the first mountain between them and Markham. [24] By dawn on the third day, the team had reached the summit. Looking back, they could still see smoke hanging in the air from their bonfire. It was not until the next morning, after putting sufficient space between themselves and the drop zone, that the agents paused to send an initial radio message back to the Tibet Task Force, reporting the navigational error and their intended movement. Even though the agents were tired and hungry, their journey over the first five days was trouble free. On day six, things started to change. Pausing near sunset, they spied ten PLA soldiers and a Khampa guide in the process of concealing an observation post near the crest of a nearby hill. Not knowing if this was a coincidence or if their presence was suspected, Tim ordered the team to detour into the bush and cache those supplies not deemed vital, such as a mimeograph machine and an inflatable rubber raft the CIA had provided for crossing the rivers that bracketed Markham. Patrolling forward, Tim and Ken made a two-man reconnaissance over the next hill and detected no other Chinese. The team continued its trek under cover of darkness. After one week of slow, careful movement, they could at last see Markham in the distance. Between them was a green valley pockmarked with the black, rounded tents used by herdsmen and traders. Though their goal was almost within reach, by that point, the agents had completely exhausted their rations and were thinking of little other than their stomachs. Leaving four members behind, Tim, Aaron, and Phillip crept toward the nearest tent in a bid to procure food. At the last moment, Tim called a halt. By sheer coincidence, he recognized the occupant as a servant of his father. Approaching cautiously, Tim offered greetings and asked the servant of his father's whereabouts. The news was heart wrenching: he had been killed during a battle with the Chinese a few months earlier. Two other local chieftains had inherited his command, said the servant, and had continued to resist near Markham until their food stocks were depleted; both were now hiding with their guerrillas in the neighboring hills. When asked, the servant admitted that locals had heard the aircraft that dropped Tim, and the Chinese had deployed patrols as a result. [25] Tim knew that he needed to act with discretion, if not suspicion. But still without rations, he imposed on the servant to convey a request for one of the rebel leaders to rendezvous with tea bricks, yak butter, and tsampa (ground roasted barley, a Tibetan staple). This meeting took place as scheduled, and although Tim received warm embraces and the customary deference afforded the son of a martyred chieftain, there was no mistaking an undercurrent of strain. By day ten, the team arranged for a meeting with another local chief. Again, pleasantries were tempered by palatable tension. It was fast becoming apparent that the agents were seen by some as an invitation for a Chinese crackdown. Persisting, Tim was finally taken to the forest redoubt where the remnants of his father's guerrilla band were holed up. Women and children were among the weary partisans, including Tim's sister. They were a sad sight, with food in short supply and footwear in tatters. Tim used the opportunity to pass on statements of encouragement from the Dalai Lama, and he tried to breathe life back into his crowd by speaking about the material support he was set to receive from the United States. As proof, he sent four of his agents to the cache site to recover their hidden supplies. On the way back, they left leaflets urging all tsampa-eaters (a euphemism for Tibetans, as opposed to Han rice-eaters) to remain vigilant against Chinese attack. Over the following week, the rebel chieftains weighed Tim's exhortation back to arms and then called an emergency meeting in his absence. Despite the promise of foreign support, more than five years of fighting had taken a heavy toll. Exile was now utmost on their minds, not ratcheting up the war against China. Deputy team leader Ken, who was present at the meeting, tried to stem the tide. Their orders, he noted, were to ex filtrate only after exhausting all means of resistance. The rebels were hardly swayed; they were intent on heading for India. By that time, the team had been on the ground for twenty-four days. After the conclusion of the emergency session, a radio message was sent notifying the Tibet Task Force about the impending rebel exodus from the hills around Markham. When no immediate reply was forthcoming, the agents saw little choice but to join them. They did not get far. News of the team had invariably spread across the Markham countryside, and it was only a matter of time before local informants tipped off the PLA. Together with pro-communist Khampa militiamen, Chinese troops closed in on the guerrilla concentration just as they started to move. Nine separate engagements were fought over the course of the first day. The agents sought refuge deeper in the forest, but not before the Chinese onslaught killed Collin and Duke. Cranking up their radio, the survivors had time to tap out a brief message. Recalls Mark, who was helping with translations in Washington at the time, "It was an SOS." Taking along fewer than two dozen guerrillas and dependents, the remaining team members slipped through the PLA cordon and for a time shook off their pursuers. Over the next three days, they attempted to rest. But again, their hunger pangs were overwhelming. After nearly running into a Chinese patrol the following morning, they left the forest to approach a lone herdsman. Upon seeing the guerrillas, the shepherd turned over a yak and hurried from the scene. Ignoring tradecraft, the famished agents butchered and cooked the animal on the spot, then ate until they were full. The PLA was not far behind. Having corralled the rebels toward a mountain, the Chinese repeated their Pembar strategy of establishing blocking positions and flushing them out by setting the forest ablaze. With no alternatives, the agents and a handful of partisans left the protection of the trees and scurried up the bare slope in the dark. The Chinese had already circled atop the summit, allowing no escape. As the sun rose, Ken took account of their bleak situation. "It was like a dream, unreal," he later commented. Squeezed behind boulders, Tim's sister and two other children could be heard weeping loudly. Aaron and Luke were huddled behind another rocky outcropping, Tim and Phillip behind a third. As the Chinese leapfrogged closer, they fired an occasional rifle shot and called for surrender. "Eat shit!" the Tibetans yelled back defiantly. By 1000 hours, the Chinese had maneuvered within a stone's throw. Surging forward, they grabbed the three bawling children. Ken fingered the cyanide ampoule hanging from a necklace around his neck. The previous night, the agents had agreed to commit suicide after firing their last shot. Seeing no movement from Aaron and Luke, Ken assumed that both had already taken their lives. Craning his head toward his remaining colleagues, Ken caught a glimpse of Tim frantically motioning toward his ampoule with sign language. Uncertain if this was a call to commit suicide in unison, Ken tentatively placed the cyanide in his cheek. Seconds later, a Chinese soldier leaped from behind and planted a rifle butt on the back of his skull. Knocked unconscious before he could bite down on the ampoule, Ken was bound and led away to a prison cell in Markham. He was the only survivor of the seven and would not see freedom for another seventeen years. *** Although the CIA did not have immediate confirmation of the fate of Tim and his team, the desperate tone of their last radio message spoke volumes. It was glaringly apparent: the task force needed a new strategy.

|

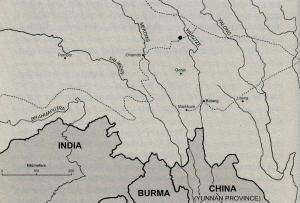

|