|

THE CIA'S SECRET WAR IN TIBET -- THE JOELIKOTE BOYS |

|

Chapter 15: The Joelikote Boys As the CIA's covert program for Tibet regained momentum toward the end of 1963, strict compartmentalization among its component projects fell by the wayside. This had become readily apparent to Wayne Sanford, who extended his tour in October to remain as the U.S. embassy's resident CIA paramilitary adviser responsible for ongoing assistance to Establishment 22. One of his first duties after extending his tour was to escort T. M. Subramanian, the intelligence officer now working under ARC, to Camp Hale. Some of the Hale trainees, it had been decided, would be redirected from agent operations to Uban's guerrillas at Chakrata. [1] The nuances in this were significant. Establishment 22 was an Indian operation supported by the Near East Division. The Hale agent training, however, had originally been conceived as a unilateral Far East Division project with limited Indian exposure. Now the assets from one division's program were being transferred to another -- and the Indians were full partners on both. Much the same thing had happened to the guerrilla army at Mustang. When first launched by the Far East Division, the Mustang operation had been conducted behind India's back. During the Harriman mission, however, Mullik had been fully briefed, and discussions over the best way of jointly running the guerrillas soon followed. The CIA and Intelligence Bureau, it was discovered, held widely disparate views on Mustang, which was home to 2,030 Tibetan irregulars as of early 1963. Less than half of them had been properly equipped during the two previous CIA airdrops. Realizing that the unarmed men were a ball and chain on the rest, the agency devised a plan to parachute weapons to an additional 700 men sent to ten drop zones inside Tibet. The purpose of this was twofold. First, it would force them to leave their Mustang sanctuary and take up a string of positions inside their homeland. Second, it would go far toward rectifying the disparity between armed and unarmed volunteers. When this plan was taken to Mullik, his reaction was poor. Just as the Indians had balked at aerial infiltration for the Hale agents, they preferred no Mustang drops by Indian aircraft (ARC was close to formation at the time), for fear of provoking the Chinese. When the CIA proposed that U.S. aircraft do the job -- but insisted on Indian landing rights -- New Delhi was again reticent. Frustrated, the CIA in the early fall of 1963 hastily arranged for an airlift company to be established inside Nepal. Allocated a pair of Bell 47G helicopters and two U.S. rotary-wing pilots -- one of whom was released from Air America for the job -- the Kathmandu-based entity, called Air Ventures, theoretically could have solved the airdrop problem by choppering supplies to collection points near Mustang. As it turned out, there was no need for Air Ventures to fly any covert missions. By September, at the same time agreement was reached on establishing a joint operations center in New Delhi, the CIA and Intelligence Bureau came up with a new plan for the unarmed men at Mustang to be reassigned to Establishment 22 at Chakrata. It was also agreed that nonlethal supplies for the armed portion of Mustang -- which was estimated at no more than 835 guerrillas -- would go overland through India and be coordinated through the New Delhi center. In addition, some of the Hale graduates would go to Mustang to assist with radio operations. Once again, distinctions between the various Tibet projects were becoming blurred. [2] During the same month, CIA officers beckoned Mustang leader Baba Yeshi to New Delhi to gain his approval for the reassignment scheme. Unfortunately for the agency, the chieftain was not happy when he was told that his force would be more than halved. With Lhamo Tsering providing translations, talks remained deadlocked for the next week. Opting to seek the counsel of Khampa leader Gompo Tashi, they shifted the debate to Calcutta. Gompo Tashi had recently returned there after half a year in a London hospital, where he had sought relief from lingering war injuries. Still weak, he refused to take sides. [3] Defiantly, Baba Yeshi went back to Mustang. From the perspective of a Khampa tribal leader, his reluctance to downsize Mustang was both understandable and predictable. In true chieftain fashion, he had spent the previous two years patiently padding his command. The results on several fronts were laudable. The bleak food situation, for example, had been fully rectified. With occasional funds channeled by the CIA, a small team of Khampas purchased meat, butter, and rice at Pokhara and sent the supplies north on pack animals. Baba Yeshi's Khampas also procured local barley for a tsampa mill they established in the Mustang village of Kagbeni. His men were eating; malnourishment was a thing of the past. [4] The quality of his fighters was also improving. Unlike Mustang's first wave of aged recruits, the steady stream of trainees arriving in Mustang during 1963 were either in their late teens or young adults. Many hailed from central Tibet, providing a more representative mix than the previous Khampa-dominated ranks. Because most of the young arrivals came with no previous guerrilla experience, the Mustang leadership had spent much of 1963 institutionalizing its training procedures. A more formal camp was set up at Tangya to offer between three and six months of drills in rock climbing, river crossing, partisan warfare, and simple tradecraft. Graduates were then posted to one of Mustang's sixteen guerrilla companies, each of which had a Hale-trained instructor for refresher courses. [5] Baba Yeshi had made some personalized gains as well. Because his headquarters at Tangya was uncomfortable during the coldest months, in 1963 he focused considerable energy on establishing a new winter base at the village of Kaisang. Located seven kilometers southeast of Jomsom, Kaisang was tucked at the base of the massive Annapurna. More than just a beautiful vista, the new base included a comfortable two-floor house for Baba Yeshi; it had a vegetable garden, Tibetan mastiffs chained to the front gate, and a Tibetan flag fluttering from a tall staff. Ten guards patrolled the perimeter, screening guerrilla subordinates who wished an audience with their commandant. Sitting in Kaisang with hundreds of loyalists under arms, Baba Yeshi had few local rivals for power. The thinly spread royal Nepalese armed forces maintained almost no presence around Mustang. Even Mustang's royalty, greatly weakened by internecine fighting during 1964, was increasingly deferential toward its Tibetan guests. In a telling gesture, the crown prince of Lo Monthang (his brother, the king, had died under mysterious circumstances earlier that year) traveled by horseback to Kaisang to attend a Tibetan cultural show hosted by the Mustang guerrilla leader. [6] Against these gains, precious little had been done to progress the war inside Tibet. In theory, the guerrillas intended to concentrate their cross-border forays during the winter, when the frozen Brahmaputra was easily fordable and the Chinese were less likely to patrol. In reality, hardly any guerrilla activities emanated from Mustang at any time of year. During all of 1963 and most of 1964, not a single truck was ambushed (land mines were occasionally laid, without any known success), and no PLA outposts were attacked. [7] One notable exception took place in mid-1964. Two years earlier, a ten-man guerrilla team had been dispatched 130 kilometers east of Mustang to establish a lone outpost in the mountainous Nepalese border region known as Tsum. Led by a thirty-two-year-old Khampa named Tendar, they had among them a single Bren machine gun and a mix of M1 carbines and rifles. Without a radio or ready source of supplies, however, little offensive action was attempted. During their few overnight forays into Tibet, Tendar and his men had seen truck traffic only once and had never inflicted any damage. [8] In early June 1964, their dry spell was set to end. Without warning, three white men bearing camera equipment appeared at the remote camp. The spokesman among the three was none other than George Patterson, the former missionary who had taught in Kham during the early 1950s and had since become an international advocate for the Tibetan cause. Patterson was now leading a British television team seeking footage of a guerrilla attack against the PLA. Speaking in the Kham dialect, the ex-missionary pleaded with Tendar to stage a raid for the cameras. [9] Hearing Patterson's pitch, the guerrilla leader was torn. He would have preferred to ask permission from his guerrilla superiors at Mustang, but Tendar was handed two sealed envelopes that the missionary said were letters of support from senior Tibetan officials. Still uncertain, Tendar went to a nearby temple and cast dice. The dice were unequivocal: they told him to stage the mission. Instructed by the fates, Tendar on 6 June began a day-long journey across the border with eight fellow guerrillas and the three foreigners. They split into four groups on a ridgeline overlooking a border road. Coincidentally, four trucks came into view that same afternoon. Tendar, in the closest group, fired his carbine at the front seat of the lead truck. After a spirited attack -- which provided plenty of good camera footage -- the guerrillas left behind three riddled vehicles and an estimated eight Chinese casualties. One Khampa was seriously injured in the face and shoulder but managed to get back to Tsum. [10] It did not take long for word of the truck ambush to spread. In the mistaken belief that Baba Yeshi had invited the cameramen along to court unauthorized publicity, CIA officers in India couriered a reprimand and stopped the flow of funds for half a year. Tendar, meanwhile, was recalled to Mustang to face a round of criticism and reassignment to an administrative job. Together, these negative repercussions were ample incentive for a return to inactivity. Said one senior guerrilla, "We went on existing for the sake of existence." [11] *** With Mustang relegated to a sideshow, the focus of joint Indo-U.S. cooperation shifted to the agent program. To monitor this effort, the New Delhi joint operations center -- dubbed the Special Center -- was formally established in November 1963. To house the site, Intelligence Bureau officers arranged to rent a modest villa in the F block of the posh Haus Khaz residential neighborhood. [12] Ken Knaus, the first CIA representative to the Special Center, arrived in India during the final week of November. Although Knaus had the perfect background for the role -- he had been heading the Tibet Task Force for almost two years -- the assignment raised some eyebrows because it resurrected an earlier turf war. When CIA assistance was still being provided without India's complicity, the Near East Division -- in the form of deputy station chief Bill Grimsley -- had assumed responsibility for coordinating the effort out of the U.S. embassy in New Delhi. Now a Far East Division representative, Knaus was back on Indian soil. According to colleagues within the division, his welcome from peers at the embassy was somewhat muted. [13] Knaus faced another opening hurdle as well. In previous years, the Tibet Task Force had counted on strong headquarters support from the Far East Division's dynamic chief, Des FitzGerald. Knaus, in fact, was one of his personal favorites. In January 1963, however, FitzGerald transferred from the Far East slot to oversee the ongoing paramilitary campaign against Cuba. His replacement, William Colby, not only was consumed by the escalating conflict in Vietnam but also was developing a pronounced aversion toward agent operations behind communist lines. [14] Despite all this, Knaus spent his first month focusing on the center's impending operations. On 4 January 1964, he was joined by a sharp Bombay native nicknamed Rabi. A math major in college, Rabi had joined the police force upon graduation but soon switched to the Intelligence Bureau. He had been assigned to its China section and spent many years operating from remote outposts in Assam and NEFA. Now chosen as the Indian representative to the Special Center, he internally transferred to the ARC. More than merely an airlift unit, the ARC was now acting as the section of the Intelligence Bureau that would work alongside the CIA on joint efforts with the Tibet agents and guerrillas at Mustang. In April, Knaus and Rabi were joined by a Tibetan representative, Kesang Kunga. A soft-spoken former district governor and monk, Kesang -- better known as Kay Kay -- came from a landed family in central Tibet. After fleeing to India, he had risen to chief editor at the Tibetan press facilities in Darjeeling. From there he oversaw the printing of Freedom, a newsweekly distributed among the refugee camps. He had been personally chosen by Gyalo Thondup to represent Tibetan interests at the Special Center. Under Kay-Kay was a small team of Tibetan assistants. Three members were former Hale translators. There was also a pool of eight Hale graduates from the 1963 training class; half provided radio assistance at the Special Center, and the other half performed similar tasks at the radio relay center being set up at Charbatia. One of the Special Center's biggest challenges was keeping its New Delhi activities secret from the Indian public. In the midst of residential housing, the presence of foreign nationals -- both the Tibetans and Knaus -- was certain to draw attention. To guard against this, Knaus (who normally came to the center three times a week) was shielded in the back of a jeep until he was inside the garage. Similar precautions were taken with the Tibetans, who were ferried between a dormitory and the center in a blacked-out van. "We were not allowed to step outside," said one Tibetan officer, "until 1972." By the time Kay-Kay got his assignment in the spring of 1964, most of the 135 agent trainees had returned to India from Hale. [15] Two dozen were diverted to Establishment 22 at Chakrata, and another eight manned the radio sets at Charbatia and the Special Center. The remainder -- slightly more than 100 -- were taken to a holding camp outside the village of Joelikote near the popular hill station of Nainital. Built close to the shores of a mountain lake and surrounded by pine and oak forests, Joelikote once hosted Colonel Jim Corbett, the famed hunter who tracked some of the most infamous man-eating tigers and leopards on record (two were credited with killing more than 400 villagers apiece). [16] As the agents assembled at Joelikote -- where Rabi promptly dubbed them "The Joelikote Boys" -- they were divided into radio teams, each designated by a letter of the alphabet. The size of the teams varied, with some numbering as few as two agents and several with as many as five; contrary to the previous year's plan to dispatch lone operatives, none would be going as singletons. As their main purpose would be to radio back social, political, economic, and military information, the CIA provided radios ranging from the durable RS-1 to the RS-48 (a high-speed-burst model originally developed for use in Southeast Asia) and a sophisticated miniature set with a burst capability and solar cells. The teams would also be charged with gauging the extent of local resistance; when appropriate, they were to spread propaganda and extend a network of sympathizers. Although they were not to engage in sabotage or other attacks, the agents would carry pistols (Canadian-made Brownings to afford the United States plausible deniability) for self- defense. During April, the first wave of ten radio teams began moving from Joelikote to launch sites along the border. Team A, consisting of two agents, took up a position in the Sikkimese capital of Gangtok. Team B, also two men, filed into the famed colonial summer capital of Shimla. Just eighty kilometers from Establishment 22 at Chakrata, Shimla had not changed much since the days the British had ruled one-fifth of humankind from this small Himalayan settlement. Three teams -- D, V, and Z -- were sent to Tuting, a NEFA backwater already host to 2,000 Tibetan refugees. Two others -- T and Y -- crossed into easternmost Nepal and established a camp outside the village of Walung. Another two teams went to Mustang to provide Baba Yeshi's guerrillas with improved radio links to Charbatia. [17] The tenth set of agents -- two men known as Team Q -- headed into the kingdom of Bhutan. The Bhutanese, though ethnic kin, harbored mixed feelings toward the Tibetans. With only a small population of its own, Bhutan had attempted to discourage further refugee arrivals after the first influx of 3,000. Then in April 1964, the country's prime minister was killed by unknown assailants. Coincidentally, this happened at the same time Team Q was crossing the border, sparking unfounded rumors that the Tibetans were attempting to overthrow the kingdom. As the rumors escalated into diplomatic protests, the two agents were quietly withdrawn, and Bhutan was never again contemplated as a launch site. [18] Aside from the stillborn Team Q and the two others at Mustang, the other seven teams had been briefed on targets before departing Joelikote. These had been generated by the CIA and Intelligence Bureau; Knaus had access to the latest intelligence for this purpose, including satellite imagery. He and Rabi then consulted with Kay-Kay, who endorsed the missions. All involved testing the waters inside Tibet to determine whether an underground could, or did, exist. [19] During the same month the teams headed for the border, Gyalo Thondup established a political party in India. Called Cho Kha Sum ("Defense of Religion by the Three Regions," a reference to Kham, Amdo, and U Tsang), the party promoted the liberal ideals found in the Tibetan constitution that had been promulgated by the Dalai Lama the previous spring. Part of Gyalo's intent was to develop a political consciousness among the Tibetan diaspora. But even more important, the party was designed to reinforce a message of noncommunist nationalism that the agent teams would be taking to potential underground members inside Tibet. Gyalo even arranged for a party newsletter to be printed, copies of which would be carried and distributed by the teams in their homeland. Getting the agents to actually cross the frontier was a wholly different matter. By early summer, three of the teams -- in Sikkim, Shimla, and Walling -- had done little more than warm their launch sites. A second set of agents in Walung, Team Y, had better luck. One of its members, a young Khampa going by the call sign "Clyde," headed alone across the Nangpa pass for a survey. He took a feeder trail north for fifty kilometers and approached the Tibetan town of Tingri. Located along the traditional route linking Kathmandu and Lhasa, Tingri was a popular resting place for an assortment of pilgrims and traders; as a result, Clyde's Kham origins attracted little attention. Better still, Tingri was surrounded by cave hermitages that offered good concealment. [20] The Indian frontier Returning to Walling with this information, Clyde briefed his four teammates. Three -- Robert, Dennie, and team leader Reg -- were fellow Khampas; the last -- Grant -- was from Amdo. Following the same route used during the survey, the five arrived at the caves and set up camp. Tingri, they discovered, was ripe for an underground. Venturing into town to procure supplies, the team took volunteers back to its redoubt for ad hoc leadership training. They debriefed the locals for items of intelligence value and used their solar-powered burst radio to send two messages a week back to Charbatia. Settling into a routine, they prepared to wait out the approaching winter from the vantage of their cave. Good luck was also experienced by the three teams operating from the border village of Tuting. Team D, consisting of four Khampas, arrived at its launch site with one Browning pistol apiece and a single survival rifle. Their target was the town of Pemako, eighty kilometers to the northeast. Renowned among Tibetans as a "hidden heaven" because of its mild weather and ring of surrounding mountains, this area had been the destination of many Khampas fleeing the Chinese invasion in 1950. The PLA, by contrast, had barely penetrated the vicinity because no roads could be built due to the harsh topography and abundant precipitation. [21] That same rainfall made the trip for Team D a slog. Covering only part of the distance to their target by late in the year, most of the agents were ready to return to the relatively appealing creature comforts in Tuting. Just one member, Nolan, chose to stay for the winter. Wishing him luck, his colleagues promised to meet again in the spring of 1965. [22] Much the same experience was recounted by the five men of Team Z. Targeted toward Pemako, they conducted a series of shallow forays to contact border villagers and collect data on PLA patrols. Finally making a deeper infiltration near year's end, they encountered some sympathizers and the makings of an underground. By that time, most of the agents were eager to return before the approaching winter. Just as with Team D, one of its members, Chris, elected to stay through spring with his embryonic partisan movement. [23] The final group of agents from Turing, Team V, was targeted eighty kilometers west toward the town of Meilling. Located along the banks of the Brahmaputra, this low-lying region featured high rainfall and lush forests. Many locals in the area, though conversant in Tibetan, were animists, with their own unique language and style of dress. Despite such ethnic differences, one of Team V's members, Stuart, had a number of relatives living in the vicinity. With their assistance, the team was able to contact a loose underground of resisters. Shielded by these sympathizers -- who even helped them steal some PLA supplies when their cache was exhausted -- the five men of Team V radioed back their intent to remain through the winter. *** Reviewing their progress in November 1964, Knaus, Rabi, and Kay-Kay had some reason for cheer. Of the ten teams dispatched to date, four had at least some of their members still inside Tibet. All four, too, had identified sympathetic countrymen. Encouraged by these results, the Special Center representatives penned plans to launch a second round of nine teams the following spring, when the mountain passes would be free of snow. Slowly, the secret war for Tibet was shifting from simmer to low boil.

|

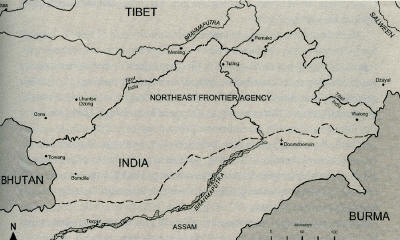

|