|

THE CIA'S SECRET WAR IN TIBET -- OMENS |

|

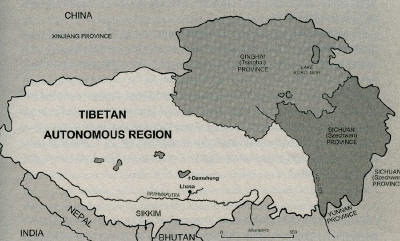

Chapter 16: Omens On the afternoon of 16 October 1964, the arid desert soil around Lop Nur in central Xinjiang Province rippled from the effect of a twenty-kiloton blast. "This is a major achievement of the Chinese people," read the immediate press communique out of Beijing, "in their struggle to oppose the U.S. imperialist policy of nuclear blackmail." [1] The detonation had not been unexpected. For the past few months, the United States had been closely tracking China's nuclear program using everything from satellite photographs to a worldwide analysis of media statements made by Chinese diplomats. India, still smarting from the 1962 war, had supported this collection effort by allowing the CIA to use Charbatia in April to secretly stage U-2 flights over Xinjiang. By late September, there were enough indications for senior officials in Washington to publicly predict the blast three weeks prior to the event. [2] Such forewarning did nothing to dampen anxiety in New Delhi. This resulted in a windfall of sorts for the Tibet project, with the CIA using the Indians' more permissive attitude to push for a series of covert initiatives aimed at raising Tibet's worldwide profile. The first such scheme was an effort to recruit and train a cadre of Tibetan officers for use as administrators and foreign representatives. An advisory committee of U.S. academics and retired diplomats was established to oversee this project, with Cornell University agreeing to play host and the CIA footing the bill. In the fall of 1964, an initial group of four Tibetans arrived at the Cornell campus for nine months of course work in linguistics, comparative government, economics, and anthropology. Among the four were former Hale translators Bill and Mark; both had been at Georgetown University over the previous two years honing their English skills. A second group, totaling eight Tibetans, arrived in the fall of the following year. Included was former Hale translator Thinlay "Rocky" Paljor and Lobsang Tsultrim, the nephew of one of the Dalai Lama's bodyguards. As a teenager, Lobsang had joined the entourage that fled Tibet with the monarch in 1959. Midway through the semester, half of the class was quietly taken down to Silver Spring, Maryland, where they were kept in a CIA safe house for a month of spy-craft instruction; all eight later reassembled, completed their studies at Cornell, and went back to India together. [3] These first dozen Cornell-trained Tibetans were put to immediate use. Three were assigned to the Special Center. Others were posted to one of the CIA-supported Tibet representative offices in New Delhi, Geneva, and New York. The New Delhi mission -- officially known as the Bureau of His Holiness the Dalai Lama -- was headed by a former Tibetan finance minister and charged with maintaining contact with the various embassies in the Indian capital. The Office of Tibet in Geneva, led by the Dalai Lama 's older brother Lobsang Sam ten, focused on staging cultural programs in neutral Switzerland. [4] The New York Office of Tibet, which included three Cornell graduates, formally opened in April 1964 following a U.S. visit by Gyalo Thondup. This office concentrated on winning support for the Tibetan cause at the United Nations, which was becoming an increasingly difficult prospect. In December 1965, Gyalo was successful in pushing a resolution on Tibet through the General Assembly for the third time, but some twenty-six nations -- including Nepal and Pakistan -- joined the ranks of those supporting China on the issue. [5] During a break from lobbying at the United Nations, Gyalo had ventured down to Washington for meetings with U.S. officials. Among them was Des FitzGerald; one of the strongest advocates of the Tibet program within the CIA, he had since left his Cuba assignment and in the spring of 1965 was promoted to deputy director of plans, putting him in charge of all agency covert operations. FitzGerald used the opportunity to invite Gyalo to dinner at the elite Federalist Club. Joining them was Frank Holober, who had returned from an unpaid sabbatical in September 1965 to take over the vacant Tibet Task Force desk within the China Branch. Remembers Holober, "Des loved Gyalo, fawned over him. He would say, 'In an independent country, you would be the perfect foreign minister.'" Gyalo proved his abilities in another CIA-supported venture. Because the Dalai Lama had long desired the creation of a central Tibetan cultural institution, the agency supplied Gyalo with secret funds to assemble a col1ection of wall hangings -- called thankas -- and other art treasures from all the major Tibetan Buddhist sects. A plot of land was secured in the heart of New Delhi, and the Tibet House -- consisting of a museum, library, and emporium -- was officially opened in October 1965 by the Indian minister of education and the Dalai Lama. It remains a major attraction to this day. *** India's more permissive attitude allowed for increasingly sensitive Indo-U.S. intelligence operations. Some efforts were in conjunction with the Republic of China on Taiwan, which was one of the few nations that equaled even surpassed India and the United States in its seething opposition to Beijing. Taipei, for example, was allowed to station Chinese translators at Charbatia to monitor PRC radio traffic. ROC intelligence officers were even permitted to open remote listening outposts along the Indo Tibetan frontier. This last effort was highly compartmentalized, even within the CIA staff in India. Wayne Sanford, the agency's paramilitary officer in New Delhi, was shocked when Indian officials escorted him to one of the border sites. He recalls, "Subramanian took me to the main listening post on October 10 (1965] , which is the big Ten Ten holiday on Taiwan. The Chinese commander saw me and asked if I had ever been on Da Chen island. I said, 'Yup.' He then asked if I had been aboard a PT evacuation boat from Da Chen. I said, 'Yup.' We then got drunk together to catch up on old times." [6] Another sensitive project combined the CIA, the Intelligence Bureau, and the top mountain climbers from both nations. Conceived in late 1964 following the first PRC atomic test, this operation cal1ed for placement of a nuclear-powered sensor atop Kanchenjunga, the third tallest mountain bordering Sikkim and Nepal. From its vantage atop the Himalayas, the sensor would theoretically relay telemetry data from intermediate-range ballistic missiles the Chinese were developing at test sites in Xinjiang. Because Kanchenjunga was later deemed too challenging -- it is one of the world's hardest peaks to scale, even without the extra weight of sensitive equipment -- the target was shifted in 1965 to India's Nanda Devi. That October, a device was carried near the summit, but before the climbers had a chance to activate its generator, worsening weather forced them to secure the equipment in a crevice until they could return the following spring. [7] Some of the most tangible Indo-U.S. cooperation was in the expansion of the ARC fleet at Charbatia. By 1964, a total of ten C-46 transports and four Helio STOL planes had been delivered to the Indians. [8] Late that year, they were augmented by two more STOL airframes that were a unique adaptation of the Helio. Known as the Twin Helio, these planes looked exactly like the single-engine version, but with two propellers placed above and forward of the wings. Developed in 1960 with the CIA's war in Laos in mind, the Twin Helio's engine's placement allowed for unrestricted lateral visibility and reduced the possibility of propeller damage from debris at primitive airstrips. Only five were ever built, with one field-tested in Bolivia during the summer of 1964 and another handed over to the CIA's quasi-proprietary in Nepal, Air Ventures, in August. [9] A Twin Helio STOL plane during USAF trials in 1961; this aircraft was

later turned over Of the planes delivered to the ARC, several received further modifications in India. To provide for an eavesdropping capability, CIA technicians in 1964 transformed one of the C-46 airframes into an electronic intelligence (ELINT) platform. This plane flew regular orbits along the Himalayas, recording Chinese telecommunications signals from inside Tibet. For some of the nine remaining C- 6 transports, ARC became a test bed during 1966 for a unique adaptation. Much like the jet packs strapped to the C-119 Flying Boxcars during 1962, four 1,000-pound rocket boosters were placed on the bottom of the C-46 fuselages to allow heavy loads to be safely carried from some of India's highest airfields. [10] Such cooperation, however, masked tension under the surface. At the highest levels of government, problems were evident by early 1964. Following the assassination of John Kennedy the previous November, the new administration of President Lyndon Johnson withheld approval of a five-year military assistance package negotiated by his predecessor. Not helping matters was the fact that Johnson was increasingly consumed by the Vietnam War, leaving him little time to thoughtfully contemplate South Asia. During the following year, bilateral strains were exacerbated by the Indo-Pakistan conflict that autumn. Pakistan initiated hostilities in August when it attempted to seize the contested Kashmir by infiltrating thousands of guerrillas. After that effort faltered, Karachi crossed the frontier with tanks. India responded in kind, leading to some of the bloodiest armor battles since World War II. For the next month, the United States remained in the background as the subcontinent teetered on the edge of all-out war. Relying on the United Nations to broker a cease-fire, Washington did little apart from cut the flow of additional weapons to Pakistan. By effectively walking away from the region, the Johnson administration infuriated both sides: India was incensed because Pakistan had used U.S. weapons; Pakistan felt betrayed because the United States, a treaty partner, had not come to its assistance. Although the special U.S. Pakistani alliance was now effectively dead, no points had been scored with India. [11] The Soviet Union, meanwhile, was patiently working overtime to mend fences with New Delhi. In September 1964, it signed a deal not only to sell India the MiG-21 jet but also to allow mass production in Indian factories. The Soviets even impinged on areas of cooperation between the CIA and the Intelligence Bureau. During 1965, Moscow offered -- and New Delhi accepted -- a pair of Mi-4 helicopters for the ARC. *** Nobody was more concerned about the deterioration of Indo U .S. relations than Ambassador Chester Bowles. No stranger to the subcontinent -- having served as ambassador to India a decade earlier -- Bowles had replaced Galbraith in the summer of 1963. The two differed in several important ways. Galbraith, the consummate Kennedy insider, left India on a high note after winning military assistance in New Delhi's hour of need. Bowles, by contrast, was a relative outsider (he reportedly made Kennedy "uncomfortable") who arrived just as the post-November 1962 honeymoon had run its course. [12] The two also differed in their attitude toward the CIA. Initially a die-hard opponent of CIA activities on his diplomatic turf, Galbraith had reversed his position during the 1962 war to become an open -- if not outspoken -- proponent of the agency's activities in the subcontinent. [13] Bowles, who inherited the CIA's cooperative ventures already in progress, was largely silent about the agency during his first two years in New Delhi. Wayne Sanford, the CIA paramilitary officer who had provided regular updates for Galbraith, had not even met Bowles for a briefing by the summer of 1965. [14] But with Indo-U.S. tension gaining momentum, Bowles became more conscious of the damage being done to bilateral intelligence cooperation. In a bid to reverse the estrangement, he lent his support to a September 1965 CIA proposal to provide the ARC with three C-130 transports, an aircraft the Indians had been eyeing for five years. The offer came at a particularly opportune time. At Charbatia, Ed Rector had finished his tour and been replaced as air adviser by Moose Marrero, who had a long history of contact with Biju Patnaik and the original ARC cadre. As it turned out, Marrero's past ties had only minimal effect. The C-130 deal encountered repeated delays, largely because the irate Indians did not want to remain vulnerable to a fickle U.S. spare- parts pipeline. In a telling request, they even asked Marrero to vacate Oak Tree and relocate to an office at the U.S. embassy compound in New Delhi. Still attempting damage control, the CIA in early 1966 offered a quiet continuation of supplies for its paramilitary projects. As Washington had officially cut all arms shipments to India and Pakistan following the 1965 Kashmir fighting, this was a significant, albeit secret, exception. Four flights were scheduled, all to be conducted by a CIA-operated 727 jet transport staging between Okinawa and Charbatia. The Indians listened to the offer and consented. But in a reprise of conditions imposed on the DC- flights of 1962, the government insisted that the flights into Oak Tree be made at low level to avoid radar -- and to avoid any resultant publicity from the resurgent anti-American chorus in New Delhi political circles. [15] *** The ARC operation at Charbatia was not the only CIA project encountering difficulties. Throughout 1964, Intelligence Bureau director Mullik had been pushing for infiltration of all the Hale-trained agents to establish an underground movement within Tibet. By year's end, the Special Center saw its limited inroads -- elements of four teams operating inside their homeland -- as a glass half full. Mullik, by contrast, saw it as a glass half empty. Whereas he had once held excessive expectations of a Tibet-wide underground creating untold headaches for China, he now saw the limitations of overland infiltrations -- especially by Khampa agents moving into areas where they did not have family or clan support. By the beginning of 1965, Mullik lashed out, claiming that the Tibetans were being coddled by the CIA. Part of the problem was that Mullik himself was vulnerable and under pressure. In May 1964, ailing Prime Minister Nehru had died in his sleep, denying the fourteen-year spymaster of his powerful patron. That October, colleagues (and competitors) saw the chance to ease Mullik out of the top intelligence slot. They succeeded, but only to a degree. Although he gave up his hat as bureau director, he retained unofficial control over joint paramilitary operations with the CIA. That position -- which was officially titled director general of security in February 1965 -- answered directly to the prime minister and oversaw the ARC base at Charbatia, the Special Center, Establishment 22, and the sensor mission of Nanda Devi. [16] With Mullik growing impatient, the Special Center readied its agents for a second season inside Tibet. Arriving in late 1964 as the new CIA representative at the center was John Gilhooley, the same Far East Division officer who had briefly worked at the Tibet Task Force's Washington office in 1960. The Indian and Tibetan officials at the center warmed to their new American counterpart. "He was a free spirit, very good-natured," said Rabi. [17] Cordial personal ties aside, little could spare Gilhooley from the dark news filtering in from Tibet. As soon as the snows cleared in early 1965, members of Team D had departed Tuting and headed back across the border to rendezvous with Nolan, the teammate they had left behind for the winter. Only then did they discover that he had already died of exposure. The remaining three agents returned to India and did not attempt another infiltration. [18] Much the same was encountered by Team Z. Departing Turing to fetch Chris, they learned that he had been rounded up during a winter PLA sweep. Radio intercepts monitored at Charbatia later revealed that Chris had refused to answer questions during an interrogation and been executed. Team Z's bad luck did not stop there. Entering a village later that summer, the men were sheltered in a hut by seemingly sympathetic locals. While they rested, however, the residents alerted nearby Chinese militiamen. As the PLA started firing at the hut, the team broke through the rear planks and fled into the forest. One of the agents, Tex, died from a bullet wound before reaching the Indian border. [19] Better longevity was experienced by the members of Team V, all five of whom had successfully braved the winter near Menling. By the spring of 1965, four elected to return to India, but Stuart, who had relatives in the area, stayed and was given permission to lead his own group of agents, appropriately titled Team VI. Two new members -- Maurice and Terrence -- were dispatched from Tuting for a linkup. By that time, Stuart was living in his sister's house north of the Brahmaputra. During his regular crossings of the river, he used boats in order to avoid Chinese troops guarding the bridges. The new agents, however, chose the bridge option, ran into a PLA checkpoint, and panicked. Drawing their Brownings, they got into a brief firefight before being arrested. The PLA quickly isolated Maurice and forced him to send a radio message back to India claiming that he had arrived safely. This was a ploy used to good effect by the Chinese, Soviets, and North Vietnamese; by capturing radiomen and forcing them to continue sending messages, communist intelligence agencies duped the CIA and allied services into sending more agents and supplies, with both deadly and embarrassing results. In the case of North Vietnam, some turned agents continued radio play for as long as a decade. [20] The Chinese were not as fortunate with Maurice. On his first message back, the Tibetan included a simple but effective duress code; he used his real name. This was repeated in two subsequent transmissions, after which his handlers ceased contact for fear the Chinese would triangulate the signals coming from Charbatia and expose the base to the press. A warning was then flashed to Stuart, who was able to get back to India. Team Y, the last of the 1964 teams still inside Tibet, had a similar experience. After successfully living alongside sympathizers near Tingri through the winter, the five agents lobbied the Special Center in early 1965 for permission to rotate back to India. Agreeing to replace them in phases, the center authorized two of the veterans -- Robert and Dennie -- to make their way out to Walung. At that point, the Special Center was in for a rude surprise. Due to operational compartmentalization, it was unaware that Establishment 22 had started running its own fledgling cross-border program. Using Tibetan guerrillas from Chakrata, a pilot team had been staged from Walung with a mandate to contact sympathizers near Tingri. It came at a bad time. To great fanfare, the Chinese were preparing to inaugurate the Tibetan Autonomous Region that fall. After nine years of ruling Tibet under the PCART, the name change signified that Beijing deemed the Communist Party organs in the region fully operational. To coincide, the Chinese began a more forceful program of suppression, purging Tibetan collaborators, establishing communes, and increasing military patrols. Not only was the Establishment 22 team caught in one of these sweeps, but Robert and Dennie ran headlong into the dragnet as well. [21] Ditching their supplies, both agents veered deeper into the hills as they evaded toward the Nangpa pass on the Nepalese border. Unfortunately for the two, the Nangpa is notoriously treacherous through late spring. Given its high elevation, it is not uncommon for entire caravans to be wiped out from slow suffocation as piercing winds blast fine powdery snow into the nose and mouth. Dennie ultimately reached Nepal; Robert did not. Back at Tingri, the rest of Team Y faced the same Chinese patrols. Two replacement agents had already arrived by that time. In need of supplies, team leader Reg left their cave retreat to procure food. Captured upon entering a village, he was forced to lead the PLA back to the team's redoubt. In the ensuing firefight, all were killed except for the lone Amdo agent, Grant. A subsequent sweep rounded up the dozens of sympathizers they had trained over the previous year. Tibet, from China's perspective The news was equally bleak for the new teams launched in 1965. At Shimla, the two-man Team C endured a deadly comedy of errors during its first infiltration attempt. Looking to cross a river swollen by the spring thaw, agent Howard fell in and drowned. His partner, Irving, spent the next three days looking for a better fording point, Cold and hungry, he chanced upon an old woman and her son tending a flock. They led him to an isolated sheep enclosure, then alerted the militia. Irving was soon heading for Lhasa in shackles. [22] Another trio of agents, Team X, was deployed to easternmost India and targeted against the town of Dzayul, renowned as an entomologist's dream because of its rare endemic butterflies. The CIA was eyeing Dzayul because the surrounding forests supposedly hosted displaced Burmese insurgents who could potentially be harnessed against the Chinese. Team X, however, found nobody of interest and came back. More bizarre was the tale of Team U. The five-man team staged from Towang, the same border town that had factored into the Dalai Lama's 1959 escape and the 1962 war. Three members headed north from Towang toward Cona, where one of the agents had family. Upon reaching their target, they were immediately reported by the agent's own brother. Arrested and bundled off to Lhasa, they were not mistreated but instead were shown films of captured ROC agents, then photos of the captured and killed members of Team Y. After less than a month of propaganda sessions, all three were given some Chinese currency and escorted to the border. After a final warning about "reactionary India," they were allowed to cross unmolested. [23] Sometimes the agents were their own worst enemy. The two members of Team F, which staged from Walung to Tingri, constantly quarreled with each other and with local sympathizers. After the more argumentative of the pair was replaced by a fresh agent, the two rushed to cache supplies for the coming winter. A final pair of Tibetans, Team S, also reached Tingri during the second half of 1965. These two agents, Thad and Troy, had better rapport with the locals than did their peers in Team F. So good was their rapport, in fact, that a local sympathizer offered them shelter in his house until spring. It was with these two Tingri teams in place that the Special Center awaited its third season during the 1966 thaw. [24] *** Although the Special Center's agent program had little to boast about, it looked positively dynamic compared with the paramilitary army festering in Mustang. A big part of Mustang's problem was that it was being managed from afar without any direct oversight. The Special Center had assumed handling of the program, but none of its officers had ever actually visited Mustang. The closest they got was when CIA representative Ken Knaus twice visited Pokhara in 1964 to meet Mustang officers, With no on-site presence, the agency and Intelligence Bureau had to rely on infrequent reporting by the Tibetan guerillas themselves. From what little was offered, it was readily apparent that the by-product from Mustang was practically nil. [25] For the taciturn Mullik, disenchantment with Mustang was starting to run deep. By late 1964, he was alternating between extremes -- first insisting that the guerrillas be given a major injection of airdropped supplies, later throwing up his arms and demanding that they all be brought down to India and merged with Establishment 22. In January 1965, the pendulum swung back -- with a twist. Now Mullik was proposing that Mustang be given two airdrops to equip its unarmed volunteers. These weapons would be given on the condition that the guerrillas shift inside Tibet to two operating locations. The first was astride the route between Kathmandu and Lhasa. The second was along the Chinese border road running west from Lhasa toward Xinjiang via the contested Ladakh region. The choice of these two locations was understandable. In late 1961, the Chinese had offered to build for Nepal an all-weather road linking Kathmandu and the Nepalese border pass at Kodari, one of the few areas on the Tibet frontier not closed by winter snows. Work was continuing at a breakneck pace, with completion of the route expected by 1966. India, not surprisingly, was concerned about the road's military applications; by putting a concentration of guerrillas astride the approach from the Tibetan side, any PLA traffic could be halted. Similarly, a guerrilla pocket along the Xinjiang road would complicate Chinese efforts to reinforce Ladakh. [26] As before, Mullik was reluctant to use the ARC to perform the supply drops. Knowing that the CIA would be equally reluctant to use its own assets -- that would defeat one of the main reasons for creating the ARC in the first place -- he offered two sweeteners. First, he promised that the U.S. aircraft could stage from Charbatia. Second, he would allow one ARC member to accompany the flights. This revised proposal went back to Washington and was put before the members of the 303 Committee (prior to June 1964, known as the Special Group); on 9 April, the committee lent its approval to the airdrop and Mustang redeployment scheme. Mullik, it turned out, was a moving target. As soon as he was informed of Washington's consent, he reneged on the offer to allow an ARC crew member on the flights. The CIA fired back, insisting that the Indian member was a prerequisite for the missions to go ahead. To this, Mullik had a ready counteroffer: he would provide a cover story if the flight encountered problems. As Mullik ducked and weaved, Ambassador Bowles urged the CIA to accept the proposal. Bowles was acutely aware that relations with New Delhi were already growing prickly on other fronts, and they were not helped when the unpredictable President Johnson unceremoniously canceled a summit that month with the Indian prime minister. Just as he would later support the stillborn C- 130 deal, the ambassador felt that a compromise with Mullik was a way to keep at least intelligence cooperation on a solid footing. The CIA agreed; the flights would proceed on an all-American basis. Now that the mission was moving forward, the agency had to decide on planes and crews. Looking over the alternatives, the CIA had only limited options. One logical source of airlift assets was Air Ventures, the Kathmandu-based company. Back in 1963, the CIA had helped establish the company; two of the airline's pilots were on loan from the agency, and its lone Twin Helio airframe had been obtained with agency approval. But once the airline began operations, the CIA station in Nepal kept its distance; Air Ventures worked almost exclusively for the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Peace Corps. [27] Moreover, the Mustang guerrillas were being handled by New Delhi; in the interest of compartmentalization, the CIA station in Kathmandu was kept wholly segregated from the operation. [28] Another logical source of air support was the CIA's considerable airlift presence in Southeast Asia. Heading that effort was the proprietary Air America, as well as select private companies such as Bird & Son, with which the agency had special contracts. Both flew airdrops under trying conditions as a matter of course. But because CIA paramilitary operations in Laos and South Vietnam were escalating by the month, aircraft were stretched thin; the CIA managers in those theaters, as a result, tightly guarded their assets. There was also the untidy matter of the press getting whiffs of the CIA's air operations in Southeast Asia; should one of these planes be downed in Tibet, a viable cover story would be that much harder to concoct. By process of elimination, the assignment was sent all the way to Japan. There the CIA operated planes under yet another of its air proprietaries, Southern Air Transport (SAT). Unlike Air America, which frequented jungle airstrips and braved antiaircraft fire over places like Laos, SAT flew regular routes into major international airports. Its cargo was sometimes classified, but its method of operation was overt and conventional. In handing the task to SAT, there was some reinventing of the wheel. Four kickers were diverted from Laos and sent to Okinawa for a week of USAF instruction in high-altitude missions, including time in a pressure chamber, turns on a centrifuge, and classes on cold-weather survival. The rest of the crew came from the SAT roster in Japan; none, with the exception of the primary radio operator, had been on the earlier Tibet flights. Taking a page from the past, SAT decided that the drop aircraft would come from its DC-6 fleet. This was the civilian version of the C-118 that had performed the Tibet missions in 1958; the only difference was a smaller cargo door in the rear. Because the smaller door meant that the supply bundles would also need to be smaller, mechanics fitted the DC-6 with a Y-shaped roller system to double the number of pallets loaded down the length of its cabin; after the first row of cargo was kicked out the door, pallets from the second row would be kicked. It was further decided to carry all the supplies aboard a single plane, rather than fly two missions as originally proposed by Mullik. In another refrain from the previous decade, SAT made a perfunctory attempt at sterilizing its plane. External markings were painted over, but the numbers quickly bled through the thin coat. Inside the plane, most -- but not all -- references to SAT were removed. "The safety belts in the cockpit still had the letters 'SAT' stitched into the material," noted auxiliary radioman Henri Verbrugghen. [29] Early on 15 May, the DC-6 departed Okinawa and made a refueling stop at Takhli. The CIA logisticians had packed the cabin to capacity, leaving little room for the kickers. Based on requirements generated by the Special Center, most of the bundles were filled with ammunition and pistols, plus a small number of M1 carbines and solar-powered radios. There was also a pair of inflatable rubber boats, to be used for crossing the wide Brahmaputra during summer. Because of the large amount of supplies involved, it was decided to make the drop inside Nepal and within a few kilometers of Tangya rather than at the more distant Tibetan drop zones used during the previous supply missions. Once at Oak Tree, the plane was taken into an ARC hangar for servicing away from prying eyes. Wayne Sanford had arranged for the provision of fuel and support for the crew. He had also requested the Indians to temporarily suppress their radar coverage along the corridor into Nepal during the final leg of the flight. For two days, the weather proved uncooperative. Not until the night of 17 May was the full moon unfettered by cloud cover. Not wasting the moment, the heavy DC-6 raced down the runway and lifted slowly into the northern sky. *** At Tangya, Baba Yeshi had gathered his officers earlier in the week for a major speech. He was a master of delivery, his voice rising and falling with emotion as he told his men that the CIA had decided to "give them enough weapons for the next fifteen years." A massive airdrop was to take place in a valley just east of their position, he said, and each company would be responsible for lifting its share off the drop zone. Although Baba Yeshi had been informed of the quid pro quo conjured in New Delhi -- weapons in exchange for a shift to positions astride the roads in Tibet -- this was not mentioned in his speech. Not surprisingly, pulses began to race as word of the impending drop flashed through the guerrilla ranks. With soaring expectations, the officers hurriedly left Tangya to assemble the necessary teams of yaks, men, and mules. [30] *** As the DC-6 headed north at low altitude, Captain Eddie Sims sent regular signals back to Oak Tree. After each one, Charbatia sent a return message confirming that he should continue the mission. Sims, who was in charge of senior pilots among all the Far East proprietaries, was held in particularly high regard by the crew on this flight. This stemmed from his role in settling a salary dispute shortly before departing Japan. As a cost-cutting measure, SAT had deemed that none of the DC-6 crew members were eligible for the bonus money regularly paid to Air America crews during paramilitary missions. After several crewmen threatened to walk out, Sims successfully lobbied management to have the extra pay reinstated. Crossing central Nepal, Sims took the plane up to 4,848 meters (16,000 feet). The rear door was then opened, allowing frigid air to whip through the cabin. Sucking from oxygen bottles, two of the kickers positioned themselves near the exit; the other two moved to the back of the first row of bundles. Looking for one final contact with Oak Tree, Sims sent his coded signal. The radioman listened for the customary response, but none came. Again Sims sent the signal, but only static crackled over the set. After several minutes of agonizing, Sims elected to proceed without the last clearance. Ahead, a blazing letter signal lit the drop zone in a small bowl-shaped valley. Dropping into a steep bank, the DC-6 came atop the signal and then pulled up sharply. In the rear, the four kickers worked furiously to get the loads out the small door. Only a fraction had been disgorged when they had to halt to allow Sims to make a sharp turn and realign. It would take yet another pass before the entire cabin was emptied. [31] *** On the ground in Mustang, the guerrillas spent the next day collecting bundles scattered across the drop zone, in the next valley, and in the one after that. Several were never found, and rumor had it that the two rubber boats were recovered by local residents and taken to the crown prince at Lo Monthang. [32] Even more harsh than the complaints over the wide disbursement was the disgruntlement over the content of the bundles. Taking Baba Yeshi at his word, those assembled at the drop zone had expected a lavish amount of weapons, enough to fight for fifteen years. Dozens of yaks and mules had been organized in what was envisioned to be a major logistical effort. "Just one plane came," lamented officer Gen Gyurme, "and it delivered mostly bullets and pistols." [33] Disillusioned, the company commanders took their allotments back to their respective camps and returned to their earlier inactivity. Radio messages were placed to Baba Yeshi over the following months, calling on him to make the shift inside Tibet, but all were answered with delays and excuses. By the end of that calendar year, few cross-border forays of any note had been staffed. As far as the U.S. and Indian representatives at the Special Center were concerned, Mustang was living on borrowed time. [35]

|

|