|

THE CIA'S SECRET WAR IN TIBET -- A PASS TOO FAR |

|

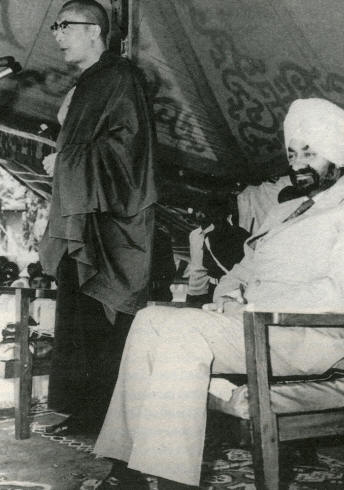

Chapter 19: A Pass Too Far Fallout from the Bangladeshi operation was swift. The CIA lodged a protest against the RAW over the use of the Tibetans in Operation EAGLE. Director Kao hardly lost any sleep over the matter; with U.S. financial and advisory support to the SFF all but evaporated, the agency's leverage was nil. Bolstering his indifference was the diplomatic furor over deployment of the U.S. aircraft carrier Enterprise to the Bay of Bengal during the brief war. Although Washington claimed that the vessel was there for the potential evacuation of U.S. citizens from Dacca, New Delhi suspected that it had been sent as a show of support for the Pakistanis. Bilateral ties, never good during the Nixon presidency, ebbed even lower. More serious were the protests against Operation EAGLE from within the Tibetan refugee community. In this instance, it was Dharamsala that was under fire, not the RAW. Facing mounting criticism for having approved the deployment, the Dalai Lama made a secret journey to Chakrata on 3 June 1972. After three days of blessings, most ill feelings had wafted away. As this was taking place, John Bellingham was approaching the end of his tour at the Special Center. He had just delivered the second installment of rehabilitation funds, which arrived in Nepal without complication. With this money, two Pokhara carpet factories had been established, and construction of a hotel in the same town was progressing according to plan. Another carpet factory was operating in Kathmandu, as was a taxi and trucking company. By the summer of 1973, with one-third of the funds still to be distributed, the CIA opted not to deploy a new representative to the Special Center. Because Bellingham had moved next door as the CIA's chief of station in Kathmandu, and because he was already intimately familiar with the demobilization program, it was decided to send him the Indian rupees in a diplomatic pouch for direct handover to designated Tibetans in Nepal. Although this violated the agency's previous taboo against involving the Kathmandu station, an exception was deemed suitable in this case, given the humanitarian nature of the project. The money was well spent. That November, ex-guerrillas formally opened their Pokhara hotel, the Annapurna Guest House. Bellingham and his wife were among its first patrons. [1] *** The Dalai Lama and Major General

Uban, the inspector general of the

SFF,

review the Although all the promised funds had been distributed, the CIA was not celebrating. Wangdu had dipped into extra money saved over previous years, defied orders to completely close the project, and retained six companies -- 600 men -- spread across Mustang. Worst of all, not a single weapon had been handed back. All this was happening as a new set of geopolitical realities was conspiring against the Tibetans. President Nixon, besides having frosty relations with India, was dedicated to normalizing ties with the PRC. In February 1972, he traveled to Beijing and discussed this possibility with Chinese leaders, who were slowly distancing themselves from the self-inflicted wounds of their Cultural Revolution. Although the phaseout of Mustang was not directly linked to this visit -- as many Tibetans have incorrectly speculated -- it is equally true that Washington had little patience for a continued Mustang sideshow, given the massive stakes involved with Sino-U.S. rapprochement. The royal Nepalese government, too, was getting a dose of realpolitik. In January 1972, King Mahendra suddenly died and was succeeded by his son, Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev. Looking around the subcontinent, Birendra had reason for concern. Pakistan had been dismembered only a month earlier, and the Indians had signed a cooperation treaty with the Soviet Union the previous August. The Dalai Lama addresses the SFF, June 1972. To his right is Major Although Nepal's security rested in astutely maintaining the nonaligned foreign policy championed by his father, the new monarch believed that it was in his kingdom's interest to offset a stronger India by fostering goodwill with Beijing. In November 1972, he dispatched his prime minister to the Chinese capital; in December 1973, Birendra himself made the trip. Following these diplomatic developments, Wangdu's residual force at Mustang counted no allies of note by the beginning of 1974. Even the local Nepalese population had turned against them. Almost since the time the guerrillas began operations, the residents of Lo Monthang had been leery of their armed Khampa neighbors. This was compounded by petty jealousy. The swaggering guerrilla bachelors, with their relatively generous food stipends, were seen as prize catches for Mustang girls. Though the men of Lo Monthang were fast to charge the Khampas with rape, their womenfolk proved more than willing to marry the guerrillas. [2] Between apocryphal tales of rape and an eagerness to demonstrate good intentions toward Beijing, the royal Nepalese government was eager to move forcefully against the long-standing affront to its sovereignty in Mustang. Playing a supporting role in this was deposed chieftain Baba Yeshi. Ever since retreating to Kathmandu in early 1970, he had been in intermittent contact with a small band of loyalists in Nashang. He had also been in touch with the Nepalese authorities and offered them assistance in confronting his rival, Wangdu. Though eager to do so, the Nepalese military, as yet untested in combat, was biding its time until conditions were right. In the spring of 1974, there arose just such conditions. As he had done in previous years, Lhamo Tsering traveled overland to Pokhara to inspect ongoing rehabilitation projects in that town. Although his trips had not been controversial in the past -- he had kept the Nepalese Home Ministry fully apprised of the guerrilla demobilization -- this time, Kathmandu saw him as a useful pawn. On 19 April, he was arrested at the Annapurna Guest House and taken to the town's police station. The Annapurna Guest House, Pokhara, built with CIA rehabilitation funds.

(Courtesy With Lhamo Tsering in detention, the Royal Nepalese Army dispatched a lieutenant colonel to Jomsom to initiate a dialogue with Wangdu. At the time, the Nepalese maintained only a single infantry company at Jomsom; not only was it outnumbered and outgunned by the guerrillas, but the Tibetans held the strategic high ground at Kaisang. But with Lhamo Tsering behind bars, Wangdu was in a conciliatory mood. Venturing down from Kaisang with a coterie of bodyguards, he offered to turn in 100 weapons in exchange for Lhamo Tsering's release. The Nepalese, suddenly emboldened, rejected the offer. With bad feelings all around, Wangdu retreated to his headquarters. Realizing that they needed more muscle, the Nepalese began mobilizing military reinforcements from around the kingdom. During June, an infantry brigade massed at Pokhara, then began walking north in driving rains to join the company already at Jomsom. Making the same hike was an artillery group consisting of a howitzer, a field gun, and a mortar. Although the Nepalese were slowly starting to develop critical mass, all their troops were green. The ranking officer at Jomsom, Brigadier Singha, had absolutely no combat experience. "None of us did," added company commander Gyanu Babu Adhikari. [3] Despite this, the government troops had sufficient confidence to deliver an ultimatum to Wangdu. His guerrillas had until 26 July (later extended by five days) to hand in their weapons; after that, the army vowed to forcibly disarm them. To add emphasis, a team of Baba Yeshi loyalists, working alongside the Nepalese, sent surrender leaflets to Kaisang. "You cannot push the sky with your finger," read one. [4] Almost until the eleventh hour, the saber rattling had little effect. But upon hearing of the impending confrontation, the Tibetan authorities in Dharamsala intervened. The Dalai Lama recorded a personal plea, and a senior Tibetan minister rushed the tape to Mustang and played it in front of the guerrilla audience. Hearing their leader implore them to disarm, the warriors broke down. Four of the six companies came out of the mountains and did as instructed. At Kaisang, one Khampa officer shot himself in the head rather than turn over his rifle. Two other guerrillas leaped to their deaths in the swift waters of the Kali Gandaki. [5] Still at large was Wangdu, backed by a pair of companies commanded by deputies Rara and Gen Gyurme. The surrender deadline had expired, and the Nepalese were contemplating their next move. Still looking to employ carrot over stick, they couriered appeals to Kaisang during early August, promising a festive celebration at Jomsom if Wangdu bowed out gracefully. When that failed, they began moving against the guerrilla headquarters. Undaunted, the Tibetans at Kaisang unpacked a recoilless rifle. They had never used this weapon inside Tibet during all the preceding years, but they now sent a round impacting into a nearby hillside. Intimidated, the Nepalese scurried back to Jomsom. "The Khampas had better weapons than we did," said Major Gyanu, "and better terrain." [6] Wangdu, meanwhile, had beckoned Rara and Gen Gyurme for what was to be their final meeting. He would make a dash west toward India with forty followers, he told them. His two deputies were to delay the Nepalese for eight days to allow him sufficient time to escape. [7] By that time, the Nepalese were gearing up for a second foray against Kaisang. Advancing at night, they surrounded the headquarters at 0300 hours. When they made a final push after sunup, however, they found only a handful of Tibetans present; Wangdu was not among them. Determined to get serious, the army made plans for a major sweep north across Mustang. The Nepalese had initially intended it as a helicopter operation -- the first in their history. Since early that year, a British squadron leader had been posted to Kathmandu to teach them such airmobile tactics. But with only four available helicopters and three inexperienced aircrews (one of the choppers was flown by a French civilian pilot), they opted instead for a long slog from Jomsom on foot. [8] Marching along the east bank of the Kali Gandaki, a single Nepalese battalion eventually reached Tangya by the end of August. In an anticlimax, the remaining guerrillas surrendered without a fight. Searching the camp, the government troops found few weapons; the rest had been cached, they presumed. At the same time, the smaller pro-Baba Yeshi faction at Nashang turned in its arms. There were no firefights at that location either. Apart from two Nepalese who succumbed to altitude sickness, nobody died during the operation. Wangdu, however, was still at large. Correctly assuming that the last two company commanders were coconspirators in his escape, the Nepalese invited Rara and Gen Gyurme to Pokhara to review the status of the rehabilitation projects. After three nights at the Annapurna Guest House, they were taken away in chains to join Lhamo Tsering. Though they had yet to capture the Mustang leader, the Nepalese authorities had a pretty good idea where he was heading. During the march north from Jomsom, the government battalion had spotted a band of horsemen riding west. Assuming that Wangdu might be destined for India, Kathmandu alerted its 4th Brigade posted along the northwestern border of the kingdom. Because there were only a limited number of passes along the frontier with India, the troops were especially vigilant at those locales. Their calculations proved correct. During the second week of September, a line of horsemen was seen approaching the 5,394-meter Tinkar Pass separating Nepal and India. Only meters from the Indian border, a Nepalese sergeant took the column under fire. Two were killed and one severely wounded; the rest escaped across the frontier. Uncertain as to the identity of the corpses, the Nepalese flew in Baba Yeshi. He positively identified Wangdu, and the traitorous chieftain had the bodies buried on the spot. Back in Kathmandu, the conclusion of the Mustang operation was celebrated with pomp. On 16 October, King Birendra handed out sixty-nine awards, including a promotion for the sergeant who had shot Wangdu. [9] Coinciding with this, a tent display was unveiled near the capital's center. In it were Buddhist scriptures and idols captured at Kaisang. Other tables held rifles, rocket launchers, ammunition, and "ultra modern miniature communication equipment powered by solar batteries." [10] Lured by the spectacle, Tibetan agents Arnold and Rocky, both still in the Nepalese capital to oversee the rehabilitation projects, filed past the display. As a macabre centerpiece, the authorities had arranged Wangdu's pistol, binoculars, watch, and silver amulet given to him by the Dalai Lama. Attitudes in Kathmandu, the two discovered, had turned decidedly hostile. To accompany the tent display, government-owned newspapers were trumpeting claims that the Mustang Khampas had conducted a twenty-six-day spree of raping and looting. "Tibetans were forced to temporarily close their shops," recalls Arnold. "It was very tense for two months." [11] *** At Pokhara, the last Mustang guerrillas were directed to temporary resettlement centers while the Nepalese authorities debated their future. Half ultimately left for India; of these, nearly 100 joined the SFF. For the remainder, favoritism was shown toward Baba Yeshi's followers formerly at Nashang; a camp was built for them near Kathmandu, with funds from the United Nations. Those loyal to Wangdu, by contrast, were given barren plots near Pokhara and, due to government intransigence, had no access to United Nations funding. [12] That was still far better than the prison cells holding Lhamo Tsering, Rara, and Gen Gyurme. Four other unrepentant guerrillas soon joined them, including the wounded member from Wangdu's escape party and a Hale-trained radioman named Sandy. They were taken to Kathmandu for trial, where the authorities were deaf to pleas for leniency. All received life sentences. *** At the Special Center in New Delhi, the Tibetan and Indian representatives had been monitoring Mustang's death throes as best they could. Until the final days of July, the radio teams at Kaisang, Tsum, Dolpo, and Limi had been sending back regular updates. Once those fell silent, gloom set in among the operatives at Hauz Khas. With a whimper, their secret war in Tibet had come to an end.

|

|