|

Bulletin

Board Pix A Higher Form

of Killing: Six Weeks in World War I That Forever Changed

the Nature of Warfare by Diana

Preston © Diana Preston

2015 Maps © Jeffrey

L. Ward 2015

CHAPTER FIVE: "The Worst of

Contrabands" BUT THE TROOPS were not even

home by Christmas. In the first few

days and weeks of the war, Germany's armies advanced through

most of

Belgium and into France, despite stronger resistance by the

Belgian army

than expected that allowed the leading elements of the

British Expeditionary

Force time to join the fighting. The German advance deprived

France of

10 percent of its territory and a third of its industrial

capacity. On September 9 the usually

cautious von Bethmann Hollweg, elated

by the speed and scale of Germany's advance, listed

extravagant war aims

for Germany. The overall goal was "Security for the German

Reich in west

and east for all imaginable time. For this purpose France

must be so weakened

as to make its revival as a great power impossible for all

time. Russia

must be thrust back as far as possible from Germany's

eastern frontier."

More specifically, France should be forced to give up the

iron ore fields of

Briey "which is necessary for the supply of our industry"

and pay a large

war indemnity. A treaty should make France economically

dependent on

Germany, excluding British commerce from French markets.

Belgium, if

allowed "to continue to exist" should be a "vassal state"

with Germany

taking military control over the Belgian coastal ports,

perhaps with the

French ports of Dunkirk, Calais, and Boulogne being added to

the vassal

state. Luxembourg should become part of Germany. Colonial

concessions

should be forced from the defeated, Germany should be

dominant in "a

central European economic association through common customs

treaties

to include France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark,

Austro-Hungary, Poland,

and perhaps Italy, Sweden, and Norway ... All its members

would be

"THE WORST OF CONTRABA OS"

formally equal but in practice would be under German

leadership and [this

will] stabilise Germany's economic dominance over

Mitteleuropa."

Other influential German leaders proposed even more

far-reaching

war aims, demanding greater territorial concessions by

France and land

seizures from Russia. One politician demonstrated Germany's

detestation

of being patronized by Britain by including among his

principal war aims

"elimination of the intolerable tutelage exercised by

Britain over Germany

in all questions of world politics." In a memorandum

submitted to government

on the same day as von Bethmann Hollweg dispatched his war

aims,

the powerful German industrialist August Thyssen demanded

the annexation

of Belgium, much of northern France inclucling the Pas de

Calais,

and in the northeast the territories on which stood the

French frontier

fortresses. To the east he demanded the Baltic states and

perhaps the Don

Basin, the Caucasus, and the Crimea for Germany. His prime

justification

was to secure "Germany's supply of raw materials."

Noteworthily, none of

these various submissions spelled out what would be the

strategy toward

Britain, merely implying it should be humble toward Germany

and as a

result of other changes commercially and militarily less

powerful.

Von Bethmann Hollweg and the others were to be disappointed

in

their dreams of a speedy victory. The German armies in the

west were held

and in places pushed back at the battles of Mons, the Marne,

and the first

battle ofYpres. Thereafter the front lines quickly began to

stabilize even if

at Ypres the British were left in an exposed salient. By ew

Year's Day

1915, a line of trenches 450 miles long stretched from

Switzerland to the

North Sea, across which 110 Allied divisions-as yet only ten

of them

British-faced 100 German ones. Over three hundred thousand

Frenchmen

and nearly a quarter of a million Germans were already dead.

Britain had

lost some thirty thousand men, nearly one fifth of its small

regular arnly.

The war of movement on the western front was over. Stalemate

had begun.

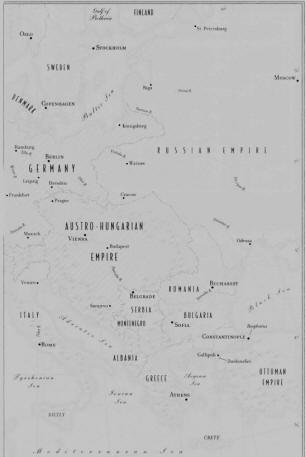

In the east too stalemate was approaching. The

Austro-Hungarian army

had lost over a million and a quarter men and the Russians

one and a half

million.

Across the Atlantic the world's other emerging great power

had

watched Europe's disintegration into war with both alarm and

a degree of

detachment and disbelief. The North Dakota Daily Herald said

of Franz

52 A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING

Ferdinand's assassination, "One archduke more or less makes

little difference."

The Philadelphia Public Ledger quipped in addressing

Austro-Hungary: "If the Serbs defeat you it will 'Servia

right'!" The Dallas

Ncu;s joined many in Europe in thinking the war would soon

be over, suggestingit

would be "long before the cotton season is." A more selious

commentator considered that the great safeguard "against the

armies and

navies Europe has gathered for war is that Europe is not

I;ch enough to

use them and is too human and humane to want to use them."

However,

Germany's im'asion of neutral Belgium turned sympathy toward

the Allies.

"As if by a lightning flash," wrote a columnist, "the issue

was made plain;

the issue of the sacredness of law; the rule of the soldier

or the rule of the

citizen; the rule of fear or of law."

Such emphasis on the rule of law chimed well with the views

of

fifty-seven-year-old Woodrow \Vilson, then in the second

year of his first

term. He had been a student of law and history, and

suhsequently a professor

at Plinceton and then president of the university. His

secretmy of

state, William Jennings Bryan, defeated three times for the

presidency, had

been essential to Wilson securing the Democratic

presidential nomination.

Like Wilson a lawyer, but also a lifelong fundamentalist

Christian and teetotaler

and more radical than \\Tilson, he championed labor lights

against

big husiness,

A strong supporter of the J Iague Treaties and of

arbitration, Blyan

saw the United States as a "republic ... becoming the

supreme moral factor

in disputes." One of his first acts as secretmy of state in

1913 was to persuade

most of the major powers (including Great Britain and France

but

not Germany) to agree to treaties committing themselves, to

some extent

at least, to the use of cooling-off perious and of

arbitration to settle international

disputes, At the signing ceremony he presented the diplomats

with

papelWeights cast in the symbolic form of ploughshares from

old swords

from Washington Naval Yard. He supplemented his income by

frequent

performances on the lecture circuit. His audiences' response

convinced

him they shared his love of peace, but many American

commentators

doubteu \vhether Blyan's intellect and political acumen

matched his eloquence

and undoubted sincerity-a view shared by diplomats with whom

he came into contact. British ambassador Sir Cecil

Spring-Rice thought

"THE WORST OF CONTRA BANDS" 53

talking to Bryan was "like wliting on ice" and Bryan

himself"a jellyfish ...

incapable of forming a settled judgement on anything outside

party politics."

Continental Europeans gagged when served nonalcoholic grape

juice

by the teetotaler as a substitute for wine at his diplomatic

receptions.

Immediately before the outbreak of war Wilson was

preoccupied with

the illness of his wife Ellen, who was dying of kidney

disease. They were a

devoted couple-he referred to them as "wedded sweethearts."

When he

first heard of Austro-Hungary's declaration of war on

Serbia, Wilson put

his hands to his face and said: "I can think of nothing,

nothing when my

dear one is suffering." Ellen died on August 6. When the

Blitish foreign

secretary Sir Edward Grey, who had lost his own wife in a

carriage accident

a few years before, wrote him a letter of condolence, Wilson

replied, "My

hope is that you will regard me as your friend. I feel that

we are bound

together by common principle and purpose." One of Grey's

main aims in

the early years of the war would be to maintain that sense

of shared understanding

and empathy with Wilson.

Nevertheless, Wilson was as committed as Bryan to

maintaining U.S.

neutrality and, if possible, to mediating peace. On August 3

he told a press

conference that America stood ready to help the rest of the

world resolve

their differences peacefully and to "reap a permanent glory

out of doing

it." On August 18 he asked his people to be "neutral in fact

as well as in

name during these days that are to hy men's souls ...

impartial in thought

as well as in action" so that the United States could "speak

the counsels of

peace" and "play the impartial mediator." Early in September

he would

make his first tentative offer to Germany to mediate, which

would be

rebuffed on the grounds that Germany had had war forced on

it and that

accepting mediation at this stage would be "interpreted as a

sign of weakness

and not understood by our people."

Even before war had begun, Wilson had shown his

determination to

ensure neutrality among his officers and offlcials by

muzzling the now

retired Admiral Mahan, who had long warned Britain through

the press of

the need to thwart German commercial and colonial ambitions

before it

was too late. On August 3 he advised the British navy to

strike at once, or

Germany would defeat France and Russia and turn on Britain.

He also

suggested that Britain should immediately make a preemptive

attack on

54 A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING

Italy, then teetering on the brink of joining Germany and

Austro-Hungary

because of a previous alliance. Under pressure from public

opinion, not

least from Italian Americans, Wilson initiated a special

order on August 6

that prohibited officers of the navy and army of the United

States, active

or retired, from commenting publicly on the military or

political situation

in Europe. Mahan asked to he exempted from the order and was

refused.

He died less than four months later on December 1, 1914,

before he could

see many of his ideas on sea power vindicated.

Sharing a language and increasingly a common popular

culture, the

American public with the exception of nearly all German

Americans and

some Irish Americans were generally sympathetic to Britain.

The kaiser

would complain in early October, "England has managed to

make the

whole world believe that we are the guilty party." However,

in reality the

actions of his troops were mainly responsihle for increased

anti-German

sentiment in the United States and elsewhere as reports

emerged of war

crimes committed by them during the early days of the German

invasion

of Belgium and France. Fearing or believing they were under

attack by

"citizen guerrillas," German troops routinely took hostages

to ensure good

behavior. They shot at least 110 citizens at Andenne Seilles

near amur and

hurned the to\ovndown. At Lerfe on the outskirts of Din ant,

German soldiers

lined up hostages-men, women, and children-in the town

square and

executed them by firing squad. The dead exceeded six

hundred.

The most well-publicized atrocity was at Louvain in Belgium.

After

German troops had occupied the city, the Belgian army

launched a counterattack

on August 25. The German soldiers panicked and over the next

five

days burned down much of the city including its world-famous

ancient

library with its 230,000 precious volumes, killed more than

two hundred

civilians, and ejected the remaining forty-two thousand

inhabitants by force

including sixteen hundred men, women, and children they

deported to

Germany. A German officer told an American diplomat who

visited Louvain

on August 28: "We shall wipe [Louvain] out, not one stone

will stand upon

another! Not one, I tell you. \Ve will teach them to respect

Germans. For

generations people will come here to see what we have done!"

Such actions were of course in direct breach of the laws of

war agreed

to internationally at The Hague. British prime minister

Herbert Asquith

"THE WORST OF CONTRABANDS 55

claimed it was "the greatest cri me against civilisation and

culture since the

Thirty Years War-the sack of Louvain ... a shameless

holocaust ... lit up

by blind barbarian vengeance." Many in Britain called for an

announcement

that when the war was won the kaiser would be exiled to

Saint Helena

as apoleon had been after his defeat at Waterloo. Others

called for those

responsible to be tried as war criminals. The dean of

Peterborough

Cathedral in England encapsulated this view: 'We may be far

still from the

final abolition of war, but we should not be far from the

end of atrocities

in war if those responsible for them in whatever rank had

the risk before

their eyes that they might have to suffer just penalties as

'common felons.' "

Unwilling for their nation to be seen as book burners and

murderers,

ninety-three German academics, scientists, and

intellectuals, including the

Nobel Prize winner vVilhelm Rontgen and future winner Max

Planck, as

well as the composer Engelbert Humperdinck and the theater

director

Max Reinhardt, signed a "Proclamation to the Civilised

World" protesting

Germany's right to have carried out reprisals and claiming

that "if it had

not been for German soldiers, German culture would long have

been swept

away."

The most likely source offriction between the Allies and the

United

States and other neutrals early in the war was action by the

Btitish navy to

enforce a blockade against goods being shipped to Germany.

On August 6

the U.S. government asked all belligerents to commit

themselves to following

the rules laid down for the conduct of maritime warfare in

the

Declaration of London which-though not ratified by either

the United

States or the United Kingdom-represented in their view the

consensus

of world opinion. In line with Grey's \vish to do all that

he could to preserve

friendly relations with the United States, Britain responded

on behalf of

the Allies with a note that seemed on the surface an

affirmative until, in

what could be construed as "small print," it reserved rights

"essential to the

conduct of naval operations."

On the second day of the war, August 5, the German navy sent

out a

requisitioned excursion steamer, the KOnigin Luise, crudely

disguised as a

British North Sea ferry. In direct contravention of the

agreement at the

Second Hague Conference which prohibited the use of

unattached mines

that would not become harmless after being in the sea for an

hour, she

A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING

began laying her cargo of 180 mines in the North Sea. HMS

Amphion, a

British light cruiser, caught up with and sank her but as

she was returning

to port hit one of the floating mines the Konigin Luise had

laid and herself

sank with considerable loss of life including most of the

survivors she had

picked up from the Konigin Luise.

In the years immediately before the war German engineers had

achieved a breakthrough in submarine design. Beginning with

the Danzigbuilt

U-lg class, all German suhmarines were fitted with diesel

engines.

Diesel was cleaner than the petrol or paraffin that fueled

earlier U-boats

and had made them, when running on the surface, "almost as

visible as

a smoke-belching steamer." It also had a higher flashpoint

which made it

safer. However, the major advantage was the reliability,

power, and endurance

of the new engines. Designed by MAN of Augsburg, they gave

the

submarines the best range-some five thousand miles-and depth

performance

in the world, meaning they could now be exploited as

independent, offensive, strategic weapons rather than

primarily defensively.

The German navy began the war with twelve such newly built

diesel-powered craft.

An event on September 22, 1914, revealed the potential of

even its

older submarines. Otto Weddigen, captain of the U-g

patrolling off the

Dutch coast, spotted three four-funneled British cruisers

steaming line

abreast straight toward him at a modest ten knots. They were

the obsolescent

British cruiser HMS Cressy and her sister ships, the Aboukir

and the

Hogue. ''''eddigen immediately attacked. Hit by a single

torpedo, the

Aboukir hegan to list as water Howed into the longitudinal

coal bunkers

running the length of the ship which had been designed to

withstand shells

not torpedoes. She capsized within twenty-five minutes. The

Hogue,

believing a mine had caused the explosion, approached to

pick up survivors

only to be hit by two torpedoes and sink in ten minutes. The

Cressy then

also tried to rescue the drowning and was torpedoed in turn.

Within barely

an hour, a single unseen enemy-an old German submarine-had

destroyed

three cruisers and killed 1,459 British sailors, about a

thousand more than

the number Nelson lost at Trafalgar.

Since in 1914 few effective devices existed to prevent

either submarine

or mine attacks, the British navy early recognized the

impracticality of

"THE WORST OF CONTRA BANDS" 57

maintaining the close blockades of enemy ports to interrupt

trade in contraband

generally accepted as legal. Strangling seaborne trade into

Germany, however, remained crucial to the navy's war

strategy and the

British quickly instituted what was in effect a distant

blockade by patrolling

the exits from the North Sea and in particular the two

hundred miles

between the Shetland Islands and the Norwegian coast. The

patrol squadron

initially comprised twelve old cruisers. After sighting a

merchant ship the

cruiser dispatched a boarding party to look for contraband.

If they found

anything suspicious they escorted the merchant vessel into a

British POlt

for more thorough examination. Commercial passenger liners

requisitioned

into the navy as armed merchant cruisers, given naval crews,

repainted "vith

camouflage paint, and fitted with a couple of four- or

six-inch guns soon

replaced the old cruisers.

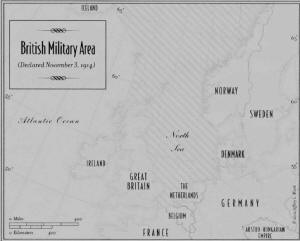

On November 2 Britain issued a declaration that the whole of

the

NOlth Sea must henceforth be considered "a British military

area" and that

as a consequence of previous and continuing illegal German

mining, Britain

would mine pmts of this zone. This would be the first but

not the last time

in the war that one country claimed "necessity" forced it to

follow its enemy

into conduct or the use of weapons banned by international

law. If neutral

shipping vessels wished to avoid the petils of mines they

should approach

the military area through the English Channel, where they

would be

stopped and searched for contraband and then escorted safely

through

British minefields to resume their journeys.

Even before November 2, the distant blockade together with

British

unilateral expansions of the definition of "contraband"-for

example, by

including goods judged by Britain to be going to Germany

through neutral

countries in "a continuous voyage"-had caused friction with

neutral maritime

nations. One American paper claimed that Britain not only

ruled the

waves but waived the rules. However, Foreign Secretary

Grey's determination

to restrict the blockade to "the maximum that could be

enforced

without a rupture "vith the United States" had resulted in

soothing responses

from Britain which, helped by Britain's willingness to pay

top prices for any

goods brought into its ports whatever their original

intended destination,

meant relations were not too heavily strained. At the same

time as declaring

the military zone, Britain wrote to the U.S. State

Department explaining

58 A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING

that only recently Germany had illegally scattered mines in

the northern

sea route from New York to Liverpool and that the yVhite

Star liner Olympic

had "escaped disaster" only by "pure good luck." Therefore,

the Admiralty

had concluded that it was "necessmy to adopt exceptional

measures appropriatc

to the novel conditions under which this war is being

waged." The

United States did not even formally protest to Britain about

the declaration

despite being pressed to do so by Norway and Sweden, hvo of

the other

leading neutral maritime nations.

Just a few days before the declaration of the militmy zone

another

issue had been delicately solved between the United States

and the Allies

using the niceties of language and legal drafting. In August

1914 the French

government had attempted to raise loans through J. P. Morgan

and

Company to finance its arms purchases. However, Secretary of

State Bryan,

believing money to be "the worst of contrabands ... it

commands all other

things," persuaded President Wilson that for American banks

to lend

money to governments at war would be "inconsistent with the

tme spirit

of neutrality." J. P. Morgan Jr., the head of the company

following his

father's death in 1913, determined to overturn this ruling

by an administration

that he despised: "A greater lot of perfectly incompetent

and

apparently thoroughly crooked people has never, as far as I

know, run or

attempted to run a first-class countIy."

He approached Robert Lansing, the fifty-year-old ew

York-born

legal counselor to the State Department. An anglophile and

ambitious

light-wing Democrat, Lansing was unkindly described by a

colleague as

"meticulous, metallic and mOl1s)'-"Neveltheless, many found

him easier

and more clearheaded to deal with than Bryan. Morgan and a

fellow New

York banker, Samuel McRobelts of National City Bank, soon

persuaded

Lansing of the advantages to U.S. commerce of a more

flexible approach

toward the financing of Allied purchases, warning that

without it the Allies

might buy elsewhere leaving the United States in its present

economic

depression. On October 23, 1914, McRoberts provided Lansing

with a

helpful note on the subject. In Blyan's absence from

Washington, Lansing

quickly copied the phraseology into a memorandum, only

inserting a few

first-person pronouns to claim the ideas as his own, then

rushed ,vith his

memo to the White House at eight thirty the same evening and

easily

"THE WORST OF CONTRABANDS" 59

secured Wilson's approval. HencefOlth, American banks would

not Olake

loans to warring governments; they would extend them credit.

The hairsplitting distinction between credits and loans was

typical of

lawyers like Wilson and Lansing. "An arrangement as to

credits has to do

with a commercial debt rather than with a loan of money" and

therefore

was "not a matter for Government," they concluded. Lansing's

stock rose

with both Wilson and Wall Street. The Allies quickly agreed

to large credits

with American banks, who in turn eagerly advanced money to

fund contracts

with American munitions manufacturers. The Nell; York Sun

rejoiced,

"All talk of stagnation in our export trade has ceased." J.

P. Morgan and

Company was soon playing a pivotal and highly profitable

role in keeping

Britain and its allies supplied with American munitions. In

1915, Britain's

imports of £238 million hom America were 68 percent greater

by volume

and 75 percent greater by value than in 1913. French imports

rose

similarly.

Appalled by the growing trade between the United States and

the

Allies, the kaiser refused to see the American ambassador,

James Gerard:

"I have nothing against Mr. Gerard personally, but I will

not see the

Ambassador of a countJy which furnishes arms and ammunition

to the

enemies of Germany." Von Tirpitz thought the United States

"contrary to

the whole spirit of neutrality ... an enemy arsenal." The

German government

continued to press the Wilson administration but it remained

unsympathetic. By JanualY 1915, Germany was pursuing another

and

illegal method of redressing what it perceived as an unfair

balance-sabotage.

A German Foreign Office telegram to its \Vashington embassy

stated,

"The sabotage in the United States can extend to all kinds

of hlctories for

war materiel" and named several contacts who could suggest

"suitable

people for sabotage." German agents quickly infiltrated the

ew York

docks and manufactured novel cigar-shaped fire bombs

designed to be

smuggled about merchant ships and to explode when the vessel

was at sea.

Elsewhere agents plotted the sabotage of infrastructure and

munitions

plants such as the "Black Tom" hlCility in New Jersey,

destroyed in 1916.

At the end of October 1914, Winston Churchill had called

seventythree-

year-old Sir Jacky Fisher out of retirement and appointed

him First

Sea Lord once more. "Lord Fisher can only think on a Turkish

rug," a

60 A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING

subordinate claimed after Fisher on his return demanded

improvements

to his Admiralty offices. Fisher began firing off his

characteristic scrawled,

heavily underlined memos in green ink designed to shake up

the navy. ''I'm

exceeding busy!" he wrote. 'Tve just told Garvin that war is

'Great

Conceptions' and 'Quick Decisions'! 'Think in Oceans,'

'Shoot at Sight.'

I'm stifling up accordingly'" However, Fisher knew that in

practice, he

could do little to defend against the submarine threat.

One area where Britain and, in particular the intelligence

unit headquartered

in Room 40 of the Admiralty building, was making progress

was

in reading German codes. On August 11 the Royal Australian

Navy captured

the German merchant shipping codebook and soon after the

Russians

took the signal book of the Imperial Navy hom a grounded

German cruiser

in the Baltic. Both were sent to London. On November 30 a

British trawler

fishing off the Dutch coast hauled up a lead-lined chest in

its nets. Inside

was the Imperial German Naval codebook-the so-called Traffic

Book used

to communicate \.vith overseas naval attaches and warships.

The captain of

a German destroyer had jettisoned the chest in desperation

while under

attack by British ships. Room 40'S personnel called the

discovery "The

Miraculous Draught of Fishes" since it provided the last

remaining information

they needed to decode messages between German warships,

submarines, and their bases-an invaluable asset in thwarting

German

plans to disrupt Britain's mastelY of the seas.

CHAPTER SIX

"England Will Burn"

As WELL AS the control of the seas Churchill and Fisher were

battling

with another issue, which had, perhaps surprisingly, become

part of the

Admiralty's remit-the control of British airspace.

Developments in both

zeppelin and airplane technology had been rapid. In ovember

1908, the

kaiser traveled to Lake Constance to see for himself what

Count von

Zeppelin's LZ3 airship was capable of. Though with tme

Pmssian hauteur

he privately considered von Zeppelin "the greatest donkey"

of all southern

Germans, his airship's performance so impressed the kaiser

that he awarded

him the Order of the Black Eagle and hailed him as "the

greatest German

of the twentieth century" and "the Conqueror of the Air."

That same year the German army ordered the 450-foot-long LZ4

from

von Zeppelin, but after only her second Hight she broke her

moorings and

burst into flames. David Lloyd George, then Britain's

chancellor of the

exchequer, visiting Germany shortly after the incident,

recalled how "disappointment

was a totally inadequate word for the gl;ef and dismay" that

swept Germany. "There was no loss of life to account for it.

Hopes and

ambitions far wider than those concerned with a scientinc

and mechanical

success appeared to have shared the wreck of the dirigible

... What spearpoint

of Imperial advance did the airship pOJiend?" A public

appeal

launched in the aftermath of the disaster raised six million

marks to allow

the now impoverished von Zeppelin to continue his work.

The army purchased further zeppelins-by the outbreak of war

it had

seven-as well as airships from the Schiitte-Lanz company,

established in

1909, whose machines had plywood rather than aluminum

frames. The

61

A HIGIIER 1"01'\:\1 OF KILLING

army believed airships' chief value in wartime would be in

scouting and

ohservation. However, the Naval Airship Division, set up in

1912, foresaw

a more attacking role. A naval officer invited his Kiel

audience to "imagine

a war with England, which from time immemorial has had an

unwarlike

population. If we could only succeed in throwing some bombs

on their

docks, they would speak with us in quite different terms.

With airships we

have ... the means of carrying the war into Britain."

British planes-unlike

zeppelins-could not fly at night and thus conld "afford no

protection

against airships."

The aval Airship Division suffered several early disasters.

In the first

fatal zeppelin accident, its inaugural airship plunged into

the North Sea in

bad weather in September 1913, taking the first head of the

Naval Airship

Division \vith it, though six crewmen survived. Five weeks

later another

exploded: "We could recognise the men looking out of the

cars," an eyewitness

desclibed. "At about fifteen hundred feet up, one of the

crew tried

to climb from the canvalk into the forward engine car ...

Then our blood

ran cold. A long thin tongue of flame leapt from the forward

gondola and

ran along the canvalk. There was a terrific explosion, the

whole earth

seemed to echo and re-echo with it. In the hvinkling of an

eye the airship

... was a mass of flames." There were no survivors and the

Naval

Airship Didsion's very future seemed uncertain until its new

head, naval

captain Peter Strasser, a neat, dapper man with a goatee,

convinced his

superiors of the airship's militalY potential.'

Airplanes also achieved success. On October 16, 1908, Samuel

Cody,

an American who had come to Britain with a Wild West show

before being

employed by the British army, flew fourteen hundred feet in

a biplane over

Famborough Common in Blitain's first successful

heavier-than-air flight.

The plane crashed on landing but Cody survived to become

such an iconic

public figure that when he died in another Hying accident in

1913, one

hundred thousand people lined the route of his funeral

procession.

On July 25, 1909, a Frenchman, Louis Bleriot, nursed his

monoplane

o Meanwhile, Count von Zeppelin had set up a company-the

Deutsche Lnftschiffahrt

Aktiensgesellschaft, known as DELAG-to operate what was

effectively the world's first

cOlllmercial airline. By July 19]4 DELAG zeppelins had

carded more than ten thonsand

passengers and flown some one hnndrecl thousand miles

between Germany's largest cities.

"ENGLA 0 WILL BURN"

in a thirty-seven-minute dawn Aight across the English

Channel to land

behind Dover Castle. The following day the author H. G.

Wells wamed

the Daily Mail's readers that "within a year we shall

have-or rather they

will have-aeroplanes capable of starting hom Calais ...

circling over

London, dropping a hundredweight or so of explosive upon the

printing

ma(;hines of The Daily Mail and retuming securely to

Calais." The previous

year his The War in the Air had conjured a nightmare vision

of "the little

island set in the silver sea ... at the end of its immunity"

as planes and giant

airships battled in the skies above.

One hundred twenty thousand people queued for a glimpse of

BIeriot's

plane when it went on display in Selfridges department store

in London.

Yet despite such popular enthusiasm on the one hand and

Wells's apocalyptic

wamings on the other, the British govemment remained

cautious

about airplanes. Sir William Nicholson, chief of the general

staff, dismissed

them as "a useless and expensive fad." A govemment committee

concluded

that planes posed no serious threat but endorsed the Royal

Navy's proposal

to acquire an airship to explore its military potential. The

craft-named

Mayfly-had a short life. As she was being readied for her

maiden flight,

crosswinds ripped her apart and British interest in airships

waned.

However, on November 1, 1911, an Italian pilot demonstrated

the

airplane's potential. In the world's first bombing raid

Lieutenant Giulio

Gavotti dropped four five-pound bombs over Turkish lines

near Tlipoli in

Libya uming an Italo- Turkish conflict. The next day,

patriotic Italian papers

rejoiced in exaggerated headlines such as AVIATOR LIEUTENANT

GAVOTTI THROWS BOMB ON ENEMY CAMP. TERRORISED TURKS

SCATTER UPON UNEXPECTED CELESTIAL ASSAULT. The Turks

claimed wrongly that the bomb hit a hospital. Italian pilots

went on to

conduct the world's first night bombing. In Morocco in 1912

the French

dropped bombs from airplanes as did pilots during the

1912-13 Balkan

conAicts. Aware of the limited eHects of such bombings and

planes' obvious

vulnerability to ground fire, Britain concentrated on

building large, slowflying,

stable craft suited to the reconnaissance role that they and

most

other govemments, including Germany's, saw as their most

promising

application. In 1914, General Douglas Haig, who at the end

of 1915 would

become commander in chief of British forces in France, was

still

A H' GHER FOR \1 0 F K' L L , N G

unconvinced airplanes were even useful for reconnaissance:

"There is only

one wav/ for a commander to Meret information ... and that

is bv_ the use of

cavalry. "

Churchill worried about Britain's vulnerability to air

attack and supported

the Aerial League of the British Empire set up by those who

believed that, just as Britannia ruled the waves, so it must

rule the skies.

League members, who included H. G. Wells, highlighted the

potential risk

to London from enemy aircraft, identifying the Houses of

Parliament as a

likely target. Lurid German publications depicting airships

laden with

explosives crossing the orth Sea to hover menacingly above

the capital

fed public fears. In June 1914, an author claiming to be a

former member

of "the German Secret Service" described a fleet of

zeppelins waiting to

attack England: "huge cigar-shaped engines of death ...

ready to drop

explosives to the ground." "Picture the havoc a dozen such

vultures could

create attacking ... London. They don't have to aim. They

are not like

aviators trying to drop a bomb on the deck of a warship.

They simply dump

overboard some of the new eXlJlosives of the German

government, these

new chemicals having the property of setting on fire

anything that they

hit ... They do not have to worry about hitting the mark ...

If they do not

hit Buckingham Palace they are apt to hit Knightsbridge."

As Chnrchilliater wrote, at the time he did not rate

airships highly: "I

believed this enormous bladder of combustible and explosive

gas would

prove to be easily destructible. I was sure the fighting

airplane ... would

hany, rout and burn these gaseous monsters." He did his best

"to restrict

expenditure upon airships and to concentrate [Britain's]

narrow and stinted

resources upon airplanes." Nevertheless, recognizing that

even if Britain

was wise not to invest in airships it needed to guard

against the zeppelin

threat, he encouraged experiments with devices like the

"Fiery Grapnel"-a

four-pronged grappling hook loaded with explosives to he

swung by airplane

pilots against the sides of airships-and "flaming bullets."

Test flights

were made with a semiautomatic cannon mounted on a plane.

However,

the gun's powerful recoil when fired caused the plane to

stall and plunge

five hundred feet. Dropping small explosive or incendiary

bombs on airships

seemed more promising.

As the war began, B,itain's meager air power was divided

between the

"E GLAND WILL BUR" 65

Royal Naval Air Selvlce (RNAS) for which Churchill and

Fisher were

responsible, and the army's Royal Flying Corps (RFC). (The

two air anTIS

would not combine into the Royal Air Force until April

1918.) The RNAS

had more than 90 planes, 53 of them seaplanes, and 7 small

airships. The

RFC possessed 190 planes. However, many of the planes of

both seIvices

were unairworthy.

With all the RFC's seIviceable airplanes dispatched to

France, on

September 3, 1914, Churchill and the Admiralty accepted

responsibility

for the air defense of Britain from the army. l\vo days

later Churchill

announced his strategy. The R AS would establish a forward

line of

defense in France and a second line somewhere between Dover

and

London. Other measures included ordeling and siting

antiaircraft guns and

searchlights and laying out floodlit landing strips in

London's parks for

British fighters. By the end of 1914, Churchill's plans had

crystallized into

a two-tier system; aircraft stationed inland should receive

sufficient warning

of zeppelins approaching London to get airborne to intercept

them while

planes nearer the coast would be waiting to attack returning

zeppelins. In

practice, however, he knew that all planes then available

would struggle to

reach the height at which zeppelins flew.

From October 1 the government imposed a blackout-limited at

first

but soon extended. The tops and sides of streetlamps were

painted black

to mask their radiance from above and people were asked to

draw their

cUltains tight. In these early weeks anxious Londoners

scanned the night

skies but no zeppelins came. During the first days of the

war the German

army lost three zeppelins on the western front. French shell

fire brought

down the first hvo while the third was fired on initially by

German soldiers

in error, then by Allied troops who shot off its rudder

leaving it to drift

helplessly before plummeting into a forest. However, any

hopes that airships

might not be as menacing or effective as feared were

extinguished

when zeppelin attacks in August and early September on Liege

and

Anhverp in support of the German advance killed a number of

civilians.

Believing the best place to attack a zeppelin was on the

ground,

Churchill ordered an RNAS raid on zeppelin sheds in Cologne

and

Diisseldorf. On October 8, 1914, hvo British pilots took off

from Anhvelp

just as Blitish troops were about to pull out of the city in

the face of a

66 A HIGIIER FORM OF KILLING

German advance. One headed for Cologne where he was unable

to find

the sheds. However, Flight Lieutenant Reggie Marix in a

Sopwith Tabloid

reached DUsseldorf and finally located a shed further

outside the city than

his map indicated. Swooping low, he released his hvo bombs:

"As I pulled

out of my dive, Ilooked over my shoulder and was rewarded

with the sight

of enormous sheets of Aame pouring out of the shee1." After

landing his

bullet-riddled plane north of Anhverp because his fuel was

running out

and finally catching up with the retreating British forces

by means of train

and bicycle, he learned that he had destroyeo a brand-new

airship.

Encouraged by what was Britain's first successful bombing

raid on

Germany and learning from intelligence reports that hvo

zeppelins had

almost been completed at the zeppelin plant in

Friedrichshafen, Churchill

ordered a fmiher RNAS raid. On November 21 four new Avro 504

biplanes,

each armed with four twenty-pound bombs, took off from

Belfort in eastern

France. Three reached Flieorichshafen and dropped nine bombs

but failed

to destroy the zeppelins. Two of the pilots returned to base

but the third

was forced to land near the burning zeppelin sheds where

local people

attacked him. German soldiers intervened and took him to a

hospital. The

German government at once accused the British of barbarously

dropping

bombs on the "innocent civilians" of Friedrichshafen despite

knowing the

only casualties had been mechanics and crewmen.

In December the RNAS targeted zeppelin sheds at Nordholz on

the

German North Sea coast. Since Nordholz was beyond the range

of any

British plane Aying fi'om Britain, France, or unoccupied

Belgium, the navy

converted three Channel passenger steamers into carriers

from which seaplanes

could be lowered into the water for takeoff. On Christmas

Day 1914,

seven RNAS seaplanes launched the raid which in foggy

conditions failecl

to locate and oestroy any zeppelins but provoked the word's

first air-sea

battle as zeppelins and German seaplanes attacked the

British seaplane

carriers and their naval escort.

The German army and navy both hoped for the glOIYof being

the first

to bomb the British mainland. Von Tirpitz wrote in mid-

ovember 1914

of his conviction that "the English are now in terror of

Zeppelins, perhaps

not without reason." Though "not in favour of

'frightfulness' "and considering

indiscriminate bombing "repulsive" when it "killed an old

woman,"

., E N G LAN D W J L L BUR N "

he saw the potential that "if one could set fire to London

in thirty places

then the repulsiveness would be lost sight of," later adding

that "all that

flies ... should be concentrated on that city." Admiral

Gustav Bachmann,

shortly to become chief of the naval staff, agreed, arguing

that Germany

"should leave no means untried to crush England, and that

successful raids

on London, in view of the already existing nervousness of

the people, would

prove a valuable means to this end." However, the army and

navy high

commands had to contend with the kaiser, who hesitated over

what the

zeppelin targets should be and in pmticular whether

zeppelins should be

allowed to bomb London, where his royal relations lived and

of which he

had sentimental memories. Chancellor von Bethmann Hollweg, a

habitual

opponent of von Tirpitz's aggressive policies, whom the

admiral would

accuse of "lukewarm flabbiness," was also reluctant.

While the kaiser pondered, German planes conducted three

small air

raids on England. On December 21, 1914, an Albatross

seaplane dropped

two twenty-pound bombs that fell into the sea near Dover

pier. In the days

that followed, a second plane dropped the first bomb to

f~lllon British soil.

It landed near Dover Castle, shattering several windows. A

third dropped

two bombs on the village of Cliffe on the Thames estumy.

Churchill believed from intelligence sources that raids on

London

itself could not be far away. On New Year's Day 1915 he told

the British

cabinet that Germany had approximately twenty airships

capable of

reaching London "carrying each a ton of high explosives.

They could

traverse the English paJt of the journey, coming and going,

in the dark

hours ... There is no known means of preventing the airships

coming,

and not much chance of punishing them on their return. The

un-avenged

destruction of non-combatant life may therefore be very

considerable."

So perturbed was Admiral Jad.)' Fisher that he suggested

Britain inform

Germany that any captured zeppelin men would be shot as

pirates. When

Churchill disagreed with him he threatened to resign but

Churchill deftly

dissuaded him.

Early in January 1915, the kaiser agreed that zeppelins

could attack

England but insisted their targets be limited to naval

shipyards, arsenals,

docks, and other military establishments in the Thames

estuary and on the

east coast, and that "London itself was not to be bombed."

On Janmuy 19

68 A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING

three naval zeppelins took ofl, aiming to inAict the damage

so ardently

demanded in a popular German song:

Zeppelin,ftieg,

Hilf /IllS ill Krieg,

FLiege nach EngLand,

EngLa/ld u;ird abgehran/lt,

Zeppelin, .flieg!

Fly Zeppelin

Help itS in W(II~

Fly to Engla lid,

England will b/lrn,

Fly Zeppelin!

L6 was only half-vay across the North Sea when engine

trouble forced

it back but L3 and L4 continued and despite rain, fog, and

sleet reached

the Norfolk coast. A young man on the ground spotted "two

bright stars

moving, apparently thirty yards apart"-the navigation lights

of the L3 and

L4. Once over land, the two zeppelins separated. At eight

thirty P. M. that

evening L3 dropped nine high-explosive bombs onto Great

Yarmouth-the

first zeppelin raid on British soil-killing a

fifty-three-year-old cobbler and

a seventy-two-year-old woman, injuring three people, and

wrecking several

houses. The L4 meanwhile headed for King's Lynn, dropping

bombs as it

went, killing nvo and wounding thirteen. A woman who watched

it drift

overhead caJled it "the biggest sausage I ever saw in my

life" and another

\ovitnessthought it resembled "a church steeple sideways."

King's Lynn was close to the royal estate at Sandlingham,

which King

George V and Queen Mary had left earlier the very day of the

attack. The

British press speculated whether the L4 had been sent

specificaJly to attack

them and raged against German ·'frightfulness." The raid

left many Britons

fearful and angry about why no advance warning had been

given or efforts

made to down the airship. Though the L4'S commander reported

having

been heavily shelled and pinpointed by searchlights, the

guns existed only

in his imagination and the "searchlights" had been the

lights of King's Lynn

penetrating the misty skies.

Neutrals like the United States, Holland, Switzerland, and

the

Scandinavian countries condemned the attacks as a clear

violation of the

Hague prohibition on the bombardment of undefended places.

The New

York Herald wondered whether "the madness of despair or just

plain

everyday madness" had prompted Germany to attack quiet

English coastal

"ENGLAND WILL BURN 69

resorts and asked "What can Germany hope to gain by these

wanton attacks

on undefended places and this slaughter of innocents?"

adding that such

behavior was no way to win the good opinion of neutrals.

In Germany the raids were greeted with exultation as

confirmation

that Britain could no longer look to the sea to keep out the

enemy. In their

wake, the kaiser agreed, albeit reluctantly, that the London

docks be

included on the list of targets. While the German army and

navy awaited

the imminent delivery of a new generation of airships

capable of reliably

reaching the city, naval zeppelins again attacked England's

east coast,

raiding from Tyneside to East Anglia.

In mid-March 1915, Ernst Lehmann, the commander of the army

airship Sachsen, diverted from an attack on Britain's east

coast by fog,

turned toward Calais where he decided to test his invention

of a tiny observation

car that could be lowered on steel cables. Its purpose to

enable

airships to survey their targets while remaining hidden in

the clouds-in

other words to provide airships with the aerial equivalent

of a submarine's

periscope. As the Sachsen hovered in clouds above Calais,

Lehmann

ordered a crewman to descend into clear air in his prototype

obsenration

car whence he telephoned precise guidance for bombing

Calais. Lehmann

described the "shattering" effect: "The anti-aircraft

batteries could hear us,

but they couldn't see us. They fired blindly into the air

•v•.ith no effect whatever.

We planted our bombs nicely, but the bombs seemed to cause

less

panic than the fact that we were invisible." Learning of

Lehmann's experiment,

a week later Peter Strasser tested the observation car for

himself

and was so impressed he ordered new naval airships to be

equipped with

them.

CHAPTER SEVEN

"A Most Effective Weapon"

By JANUARY 1915, only four months into the war, both the

British and

German governments were developing strategies to break the

stalemate

that had already ensued. The British War Cabinet, with

Winston Chnrchill

playing a prominent role, saw the solution in a naval

expedition to the

eastern Mediterranean. Their plan was to control the

Dardanelles, the

heavily guarded strait leading from the Aegean through the

Sea of Marmara

to the Black Sea, so that, at a minimum, they could get

supplies through

to Russia and, at best, force Ottoman Turkey, which had

joined the Austro-

German alliance at the end of October 1914, quickly out of

the war. Success

might draw Greece and perhaps Bulgmia and Rumania into the

Allied

camp. Churchill believed that "at the summit true politics

and strategy are

one. The manoeuvre which b,ings an ally into the field is as

serviceable as

that which wins a great battle." To that end he was also

taking a leading

role in the wooing of Italy to join the Allies. Conscious of

the need for new

weapons to break the deadlock in the trenches, in February

he gave the

Admiralty's SUPPOltand ftmding to the development of "land

ships." Under

their code name of "tanks" they would make their first

appearance on the

battlefield in September 1916 and first be used en masse at

the Battle of

Cambrai in 1917 and become one of the lasting major advances

in weaponry

of the First World War.

Perhaps surplisingly for a nation whose power was

historically land

based, one of the principal areas to which Germany was

looking to break

the deadlock was the sea and the suhmatine. At the beginning

of the war,

Germany's U-boats had been used to attack enemy warships

like the Cressy

7°

A MOST EFFECTIVE WEAPON 71

and troop transports, leaving surface vessels to do the

commerce raiding.

However, on October 20, 1914,a V-boat captain demonstrated

the V-boat's

potential as a commerce raider. Captain Johannes

Feldkirchner in U-17

forced the British merchant ship Glitm to stop in waters off

Norway. He

briefly searched her cargo of whisky and sewing machines and

ordered her

crew into their boats. The U-17 then sank the Glitra but

obligingly towed

her laden lifeboats for a qualter of an hour toward the

shore. The Glitra

was the first British merchant ship to be sunk by a V -boat

and, as he sailed

home to Germany, Feldkirchner worried how his superiors

would react.

According to a fellow V-boatman his action was "entirely

unexpected.

Attacks on commercial steamers had not been foreseen. The

possibilities

... had not been anticipated." Feldkirchner need not have

been

concerned. He was commended for his attack.

Lack of a single head of the navy bedeviled German naval

policy.

Although the inspiration of Germany's naval buildup and

preeminent in

naval matters before 1914- instantly recognizable by his

great domed bald

head and forked white beard-Secretary of the Navy von

Tirpitz was formally

only head of the Imperial Naval Office, responsible for

finance and

political affairs, including new construction and budgets.

Admiral Fliedrich

von Ingenohl commanded the High Seas Fleet. Separate from

both was

the Admiralty Staff headed in January 1915by Hugo von Pohl,

responsible

for planning and directing operations in war in a way

analogous to a land

army's general staff. Finally, there was the kaiser's naval

cabinet under

Georg von MLiller. All reported direct to the kaiser and

policy decisions

rested with him alone.

In October Hermann Bauer, commander of one of Germany's

submaline

Aotillas, had, unknown to his crews, already suggested to

his superior

von Ingenohl using submarines as commerce raiders.

Feldkirchner's success

confirmed the practicability of the idea. Von Ingenohl

circulated the

proposal to von Pohl and others, writing, "From a purely

military point of

view a campaign of submarines against commercial traffic on

the British

coasts will strike the enemy at his weakest point and will

make it evident ...

that his power at sea is insufficient to protect his

imports." Von Pohl worried

about the restrictions of international law since submarines

would find it

extremely difficult to follow the Cruiser Rules-V-boat

commanders were

72 A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING

already complaining how hard it was to distinguish enemy

shipping from

neutral vessels. He knew too that surfacing to stop and

search would expose

fragile submarines to enemy attack.

However, von Pohl changed his mind after what he saw as

Britain's

attempt to stan;e Germany when Britain in November 1914

declared the

"militalY area" and made all food contraband-the latter on

the grounds

that one could not be sure whether food was for militaIY or

civilian use and

that in case of shortage militmy requirements would take

priority over

civilian. \\Then he saw the proposal Chancellor von Bethmann

Hollweg was

concerned about the effect on neutrals such as the United

States. The

kaiser too worried about neutrals but also about killing and

'vvounding

women and children, and would not endorse the action. Von

Pohl persisted.

Von Tirpitz, often opposed to von Pohl in the maneuvering

for support in

the German naval hierarchy, then threw his authority behind

the use of the

submarine, convinced it was Germany's "most effective

weapon." A young

naval officer admired how von Tirpitz "fought, with a

doggedness which

can hardly be described ... for the inauguration of

intensified U-boat

warfare."

At the end of November von Tirpitz gave an interview to a

Germanborn

American journalist in which he criticized the United States

for not

protesting against the British military zone and asked," ow

what will

America say if Germany institutes a submarine blockade of

England to stop

all traffic?" When the journalist asked whether Germany was

going to do

so, von Tirpitz responded, "Why not? ... England is

endeavoming to starve

us. We can do the same, cu t off England and sin k every

vessel that attempts

to break the blockade." The article when published in

Germany received

great support from naval officers, and von Pohl and von

Tirpitz pressed

hard for a submmine campaign. In mid-January von Tirpitz

told the kaiser

that if Germany did not use the submarine "to get our knife

into the

English ... we should accomplish nothing."

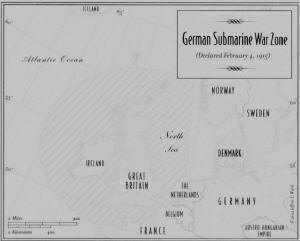

On February 4, his last day as chief of the naval staff

before he succeeded

von Ingenohl as commander of the High Seas Fleet and was

himself

succeeded by Admiral Gustav Bachmann, von Pohl accompanied

the kaiser

to some naval exercises at vVilhelmshaven. \Vhile the

emperor was preoccupied

with the maneuvers, von Pohl secured his signature on a

declaration

A MOST EFFECTIVE WEAPON" 73

agreeing the launch of a campaign of unrestricted submarine

warfare

whereby enemy merchant vessels would be sunk without search

or even

warning and citing as justification Britain's blockade of

Germany. From

February 18, the waters around Great Britain, except for a

designated route

north of Scotland from the Atlantic to Scandinavia, would be

a war zone in

which all enemy ships "would be destroyed even if it is not

possible to avoid

thereby the dangers which threaten the crews and passengers

... It may

not always be possible to prevent the attacks meant for

hostile ships from

being directed against neutral ships." In a telegram to its

Washington

embassy, Berlin was even more specific, advising that

"neutral vessels will

not in most cases be recognizable as such in the war zone

and will therefore

be destroyed without more ado." The embassy was instructed

to use the

press to warn American vessels to keep clear of the war zone

"to avoid

dangerous complications."

Not long afterward, Berlin dispatched another telegram to

Washington

containing the draft of a notice to be inserted by

Ambassador Count Johann

von Bernstorff in the American press, warning Americans

against traveling

through the war zone on British ships or those of its

allies. "Thinking it a

great mistake," von Bernstorft" threw it into his desk

drawer and "hoped

Berlin would forget about it."

U-boats were now equipped with machine guns, grenades, and

formal

instructions about contraband. Shipping schedules were

distributed and

scarce copies of the British-produced Lloyd:~ Register

listing evelY ship in

the world became a highly plized aid to identifying targets

for German

submariners.

Despite the German declaration of unrestricted U-boat

warfare, the

British navy continued throughout the war to follow Cruiser

Rules in any

attacks their submarines made against merchant vessels-a

decision made

easier not only by the need to retain the good will of

neutral governments

like the United States, but also by the limited num ber of

German merchant

vessels still operating- almost exclusively in the Baltic or

coastal waters.

When the war began the British and German governments

requisitioned

passenger liners and converted them for war duties as armed

merchant cruisers. The British Admiralty reminded Cunard of

its agreement

to hand over the Lusitania and the Mauretania but then

decided

74 A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING

neither was suitable as an auxiliary cruiser-they simply

consumed too

much coal. The Mauretania was dazzle-painted to camouflage

her for duty

as a troop transport and hospital ship. Although having had

four six-inch

gun rings fitted in 1913 to her deck to allow guns to be

mounted quickly

in wartime, the Lusitania was left unarmed with Cunard to

continue the

commen.:ial transatlantic run, but under strict conditions.

The Admiralty

would inform her master of the course she was to follow; any

contact

between Cunard and the ship, while at sea, must be through

the Admiralty;

her cargo space must be at the Admiralty's disposal.

By the beginning of 1915 the Lusitania was the only one of

the great

prewar liners of any nation still plying the Atlantic

although some smaller

British, U.S., and other neutral vessels were also making

the crossing. The

British Admiralty's Room 40-using improved instruments

developed by

Guglielmo Marconi-was able to pick up German transmissions

to and

from U-boats for the day or two after they left port before

they were out

of range of radio contact with their base. Among some of the

early targeting

information they intercepted and decoded was: FAST STEAMER

LUSITANIA

COMING FROM NEW YORK EXPECTED AT LIVERPOOL 4TH

OR 5TH MARCH. The purpose of the communication was clear

especially

compared with another sent to U-boats: AMERICAN SS

PHILADELPHIA

AND WEST HAVERFORD WILL PROBABLY ARRIVE IN THE IRISH

SEA BOUND FOR LIVERPOOL. BOTH STEAMERS ARE TO BE

SPARED. Obviously the Lusitania was not.

On March 2 U-27 lay submerged on the approaches to

Liverpool. In

his war uiary, her captain recorded letting several tempting

targets pass

close by because "the Lusitania was expected to arrive in

English waters

on 4 March and in my present position I believed I had a

good chance of

attacking her." On March 5, he turned reluctantly homeward.

The Lusitania

arrived a few hours later. On this occasion the British

Admiralty had tried

to provide her with a naval escort but it failed to

rendezvous with the liner

due to a comic opera series of communication failures.

WOODROW WILSON HAD recognized early in 1915 that the

stalemate

in the war offered a good opportunity for America to lead

arbitration to

A MOST EFFECTIVE WEAPON" 75

secure a peace settlement before casualties rose too high

and both military

and political positions became too entrenched to allow

concessions. He

sent Colonel House on a secret mission to investigate the

prospects for a

broke red peace. The small, softly spoken, slightly frail

House, whose rank

was an honorary one, was throughout the war Wilson's most

trusted adviser.

Wilson wrote of him "Mr. House is my second personality. He

is my independent

self. His thoughts and mine are one." Surprisingly, given

his

neutral status, House sailed to Britain not on an American

ship but on the

Lusitania.

Nearing the Irish coast in early February the Lusitania

raised the U.S.

flag. The press pursued House about the incident as soon as

he landed. He

wrote in his diary: "Every newspaper in London has asked me

about it, but

fortunately, I was not an eye witness to it and have been

able to say that I

only knew it from hearsay." The incident caused fury in

Germany, which

insisted that it was illegal for British shipping to hide

behind neutral flags.

In the United States fears were roused that U-boats would

attack AmeJican

vessels suspecting they were disguised as enemy ships.

President Wilson

protested to London that using neutral flags would create

intolerable risks

for neutral countJies, while failing to protect British

vessels. The British

government responded blandly that the Rag had been Rown at

the request

of the Lusitania's American passengers to indicate that

there were neutral

Americans on board. Germany's declaration that it would sink

British merchant

ships on sight made such actions necessary and legitimate.

The U.S. government's reaction to the German promulgation of

unrestricted

submarine warfare was much harsher than exchanges with

Britain

about the blockade or the use of neutral Rags. On Februmy 10

President

Wilson declared that Germany's action violated the rights of

neutral countries

and that it would be held "to a strict accountability" for

any consequent

loss of'American life and any deprivation of American

citizens' "full enjoyment

of their acknowledged rights on the high seas." The two

words "strict

accountability" would achieve great significance in the

months ahead.

However, von Pohl expected Britain to be brought to its

knees by the submarine

campaign within a few weeks and von Tirpitz was soon

rejoicing in

the "magnificent" work of the German submarines, thinking

their war diaries

"as exciting as novels."

A HIGHEH FOHM OF KILLING

The U.S. threat to hold Germany to account \-vasquickly

tested when,

on March 28, 1915, the V-28 sank the SS Falaba, an unarmed

British

passenger-cargo ship of five thousand tons, in the recently

declared war

zone off the southern Irish coast. More than one hundred

people died

including one American, mining engineer Leon Thresher, bound

for \Vest

Africa from Liverpool. The Falaba was given some warning by

the V-28's

commander, who had surf~lced. However, he did not allow many

minutestwenty-

three according to the V-boat war clialY,seven according to

Blitish

accounts-for evacuation before firing a single torpedo. The

American

press called the sinking "a massacre" and "piracy" but

President Wilson

avoided invoking the doctrine of "strict accountability" or

reacting formally

in any way.

Churchill thought the U-boat campaign was in fact having

little impact.

By the end of its first week, out of 1,381 vessels arriving

or departing hom

British ports only eleven had been attacked and seven sunk.

During the

second week, only three ships were attacked and all escaped.

By April the

British press was rejoicing that inward and outward sailings

were now running

above fifteen hundred a week. Churchill even believed

celtain political

advantages could be found in the new situation. On Februmy

12, he had

written to the president of the Board of Trade, \Valter

Runciman, that it

was "most important to attract neutral shipping to our

shores, in the hope

especially of embroiling the United States \-vith Germany

... For our part

we want the traffic-the more the better; and if some of it

gets into trouble,

better still."

Churchill had, however, on FcbruaJY 10 issued instructions

to merchant

captains to avoid headlands, steer a mid-channel course,

operate at

full speed off harbors, and post extra lookouts. If attacked

by a su bmarine

they should do their "utmost to escape" but if they could

not they should

steer for tile submarine "at utmost speed" to force it to

dive. The word

"ram" was not used but ramming was clearly what was meant.

When the

Germans discovered these instructions they protested, saying

any merchant

captain who attempted to ram would, if captured, be treated

as a climinal.

On July 27, 1916, the German authorities would execute

Captain Charles

Fryatt, a BIitish merchant captain who in March 1915 had

saved his ship

from a V -boat by attempting to ram it but had been captured

on a

A MOST EFFECTIVE WEAPON" 77

subsequent occasion. Prime Minister Asquith would describe

their action

as "terrorism," continuing: "It is impossible to guess to

what further atrocities

[the Germans] may proceed. His Majesty's Govemment therefore

desire to repeat emphatically that they are resolved that

such crimes shall

not ... go unpunished ... They are determined to bring to

justice the

criminals, whoever they may be and whatever their station

... The man

who authorises the system under which such crimes are

committed may

well be the most guilty of all."

Although he had not accepted Fisher's intemperate proposal

to promulgate

that captured zeppelin crews would be shot, Churchill

ordered that

in the future any captured V-boat crewmen should not be

treated as ordinary

prisoners of war but segregated for possible trial as

pirates at the

conclusion of hostilities. In retaliation, the German

authorities placed in

solitary confinement thirty-nine captured British officers,

picking those

whom they supposed related to the most prominent families in

Great

B,itain. Among them was one of Sir Edward Grey's relations.

An outraged

British press demanded that any special privileges given to

von Tirpitz's

son, a naval officer captured earlier in the war, should be

removed.

CHAPTER EIGHT

"Something That Makes People

Permanently Incapable

of Fighting"

As WELL AS considering new strategies to secure a quick

victOlY, the

German high command had begun to consider new weapons to

achieve

the same end. As early as September 1914, General Erich von

Falkenhayn,

minister of war at the war's start but since mid-September

chief of the

general staff succeeding General Helmuth von Moltke, whom

the kaiser

had ordered to report sick following what he thought of as

his mistakes at

the Battle of the Marne, concluded that "the ordinary

weapons of attack

had often failed completely ... A weapon bad, therefore, to

be found which

was superior to them but would not excessively tax the

limited capacity of

the German war industry ... Sucb a weapon existed in gas."

He turned to

Germany's industlialists and scientists to provide it.

Among those who responded was a bespectacled, shaven-headed,

forty-six-year-old Prussian chemist and future Nobel Prize

winner, Fritz

Haber, the director of the newly established Kaiser Wilhelm

Institute for

Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in the Berlin suburb

of Dahlem.

Haber's path to prominence had not been straightforward.

Born in 1868

into a wealthy Jewish famil~' in Breslau (now Polish

\Vroclaw), his mother

had died three weeks later, a loss from which his father,

Siegfried, took

many years to recover. Siegfried Haber was a businessman

trading primarily

in dyes. Since he bad started his business the nature of

dyes had

"s 0 MET H I N C T HAT M A K ESP E 0 P L E 79

been changing-formerly they were made from mainly organic

substances

but now most were synthetic dyes of which Germany had become

the

world's leading producer, as with so many other chemicals.

The nineteenth century is often said to be the century of

chemistry,

just as the twentieth is that of physics. To the young

Haber, as to many,

chemistry seemed the key to Germany's economic advance. In

1886, restless

and with little interest in the hlmily business, he

convinced his father

to allow him to study chemistry at Berlin University.

Finding the work less

than stimulating he moved to Heidelberg to study under

Robert Bunseninventor

of the eponymous burner--only to find him a dull teacher and

return to Berlin. When he reached twenty, the one year's

military selvice

that was the minimum obligation for all German males

intervened and he

was posted to an artillery regiment in his hometown of

Breslau-his first

contact with the military. He enjoyed the army, became a

noncommissioned

officer, and aspired unsuccessfully to be an officer.

Military service over, Haber returned to Berlin again where

in 1891

he completed his doctorate. By now interested in physical

chemistry, a new

subject combining the two sciences, he applied to join the

Leipzig laboratory

of the leading exponent but was rejected. Using his business

contacts

and still hoping his son would join the family firm,

Siegfried Haber then

arranged three short apprenticeships in chemical companies

for him to gain

industrial expelience. Perhaps despite himself the young

Haber found

industrial processes stimulating, supplementing as they did

his academic

knowledge. At a Budapest distillery he saw how potash was

extracted from

residues left over from distilling molasses. At a chemical

plant northwest

of Kracow he first became acquainted with the new Solvay

process using

ammonia to produce sodium carbonate, a key component in the

production

of glass and soap. Although he dismissed the neighboring

countryside as a

monotonous "wasteland of sand, swamp, and fever"-(it would

become the

site of Auschwitz)-he thought the plant was dominated by "a

splendid and

energetic intelligence" and was grateful to visit. His third

apprenticeship

was at a cellulose factory.

Shortly afterward at his father's urging he reluctantly

joined the family

business. Six months of tension and argument followed,

culminating in a

major dispute over a business venture in which the young

Haber purchased

80 A HIGHER FORM OF KILLING

a large amount of chloride of lime for use as a disinfectant

during a cholera

outbreak in Hamburg, only to be left with it when the

outbreak subsided

unexpectedly quickly. As a result of the argument, he left

Breslau and his

father's business to work as an unpaid laboratOl)' assistant

in lena while