|

Bulletin Board Pix

The Asset Price

Meltdown and the Wealth of the Middle Class The Asset Price Meltdown and the Wealth of the Middle Class

Edward N. Wolff

New York University

November 2013

Abstract: I find that median wealth plummeted over the years

2007 to 2010, and by 2010 was at its

lowest level since 1969. The inequality of net worth, after

almost two decades of little movement, was

up sharply from 2007 to 2010. Relative indebtedness

continued to expand from 2007 to 2010,

particularly for the middle class, though the proximate

causes were declining net worth and income

rather than an increase in absolute indebtedness. In fact,

the average debt of the middle class actually

fell in real terms by 25 percent. The sharp fall in median

wealth and the rise in inequality in the late

2000s are traceable to the high leverage of middle class

families in 2007 and the high share of homes

in their portfolio. The racial and ethnic disparity in

wealth holdings, after remaining more or less stable

from 1983 to 2007, widened considerably between 2007 and

2010. Hispanics, in particular, got

hammered by the Great Recession in terms of net worth and

net equity in their homes. Households

under age 45 also got pummeled by the Great Recession, as

their relative and absolute wealth declined

sharply from 2007 to 2010.

1. Introduction

The last two decades have witnessed some remarkable events.

Perhaps, most notable is the

housing value cycle which first led to an explosion in home

prices and then a collapse, affecting net

worth and helping to precipitate the Great Recession. The

housing bubble, in turn, was based on

questionable mortgage practices and then speculative

over-building.

The median house price remained virtually the same in 2001

as in 1989 in real terms.1

However, the home ownership rate shot up from 62.8 percent

in 1989 to 67.7 percent in 2001

according to data from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF).

Then, 2001 saw a recession (albeit a

short one). Despite this, house prices suddenly took off.

The median sales price of existing one-family

homes rose by 17.9 percent in real terms nationwide.

However, from 2004 to 2007 housing prices

slowed, with the median sales price of existing one-family

nationwide advancing only 1.7 percent over

these years in real terms. Over the years 2001 to 2007 real

housing prices gained 18.8 percent. The

home ownership rate continued to expand, though at a

somewhat slower rate, from 67.7 to 68.6

percent.

Then, the Great Recession and the associated financial

crisis hit at the end of 2007 and asset

prices plummeted. From 2007 to 2010, in particular, the

median price of existing homes nose-dived by

21 percent in nominal terms and 24 percent in real terms.2

Moreover, for the first time in 30 years, the

share of households owning their own home fell, from 68.6 to

67.2 percent.

The housing price bubble was fueled in large part by a

generous expansion of credit available

for home purchases and re-financing. This took a number of

forms. First, many home owners refinanced

their primary mortgage. However, because of the rise in

housing prices, these home owners

increased the outstanding mortgage principal and thereby

extracted equity from their homes. Second,

many home owners took out second mortgages and home equity

loans or increased the outstanding

balances on these instruments. Third, among new home owners,

credit requirements were softened,

and so-called “no-doc” loans were issued requiring none or

little in the way of income documentation.

Many of these loans, in turn, were so-called “sub-prime”

mortgages, characterized by excessively high

interest rates and “balloon payments” at the expiration of

the loan (that is, a non-zero amount due

when the term of the loan was up). All told, average

mortgage debt per household expanded by 59

percent in real terms between 2001 and 2007 according to the

SCF data, and outstanding mortgage

loans as a share of house value rose from 0.334 to 0.349,

despite the 19 percent gain in real housing

prices (see Table 4 below).

In contrast to the housing market, the stock market boomed

during the 1990s. On the basis of

the Standard & Poor (S&P) 500 index, stock prices surged 171

percent between 1989 and 2001.3

Stock ownership spread and by 2001 over half of U.S.

households owned stock either directly or

indirectly. However, the stock market peaked in 2000 and

dropped steeply from 2000 to 2003,

recovered somewhat in 2004, and then rebounded from 2004 to

2007. Over the period from 2001 to

2007, the S&P 500 was up 6 percent in real terms. However,

the share of households who owned stock

either directly or indirectly fell somewhat to 49 percent

from 52 percent in 2001. Then came the Great

Recession. Stock prices, based on the S&P 500 index, crashed

from 2007 to 2009 and then partially

recovered in 2010 for a net decline of 26 percent in real

terms. The stock ownership rate also once

again declined, to 47 percent.

Real wages, after stagnating for many years, finally grew in

the late 1990s. According to BLS

figures, real mean hourly earnings gained 8.3 percent

between 1995 and 2001. From 1989 to 2001,

real wages rose by 4.9 percent (in total), and median

household income in constant dollars inched up

by 2.3 percent. 2001.4 Employment also surged over these

years, growing by 16.7 percent.5 The

(civilian) unemployment rate remained relatively low over

these years, at 5.3 percent in 1989, 4.7

percent in 2001, with a low point of 4.0 percent in 2000,

and averaging 5.5 percent over these years.6

Real wages then rose very slowly from 2001 to 2007, with the

BLS real mean hourly earnings up by

only 2.6 percent, while median household income gained only

1.6 percent. Employment also grew

more slowly over these years, gaining 6.7 percent. The

unemployment rate remained low again, at 4.7

percent in 2001 and 4.6 percent in 2007 and an average value

of 5.2 percent.

Real wages, on the other hand, picked up from 2007 to 2010,

with the BLS real mean hourly

earnings increasing by 3.6 percent. In contrast, median

household income in real terms declined

sharply over this period, by 6.4 percent . Moreover,

employment contracted over these years, by 4.8

percent, and the unemployment rate surged from 4.6 percent

in 2007 to 10.5 percent in 2010, though it

did come down a bit to 8.9 percent in 2011.

There was also an explosion of consumer debt leading up to

the Great Recession. Between

1989 and 2001, total consumer credit outstanding in 2007

dollars surged by 70 percent and then from

2001 to 2007 it rose by another 17 percent.7 There were a

number of factors responsible for this. First

credit cards became more generally available for consumers.

Second, credit standards were relaxed

considerably, making more households eligible for credit

cards. Third, credit limits were generously

increased by banks hoping to make profits out of increased

fees from late payments and from higher

interest rates.

Another source of new household indebtedness was from a huge

increase in student loans.

According to the SCF data, the share of households reporting

an educational loan rose from 13.4

percent in 2004 to 15.2 percent in 2007 and then surged to

19.1 percent in 2010.8 The mean value of

educational loans in 2010 dollars among loan holders only

increased by 17 percent from $19,410 in

2004 to $22,367 in 2007 and then by another 14 percent to

$25,865 in 2010. The median value of such

loans first went up by 19 percent from $10,620 in 2007 to

$12,620 in 2007 and then by another 3

percent to $13,000 in 2010. These loans were heavily

concentrated among younger households and, as

we shall see below, was one of the factors (though not the

principal one) which led to a precipitous

decline in their net worth between 2007 to 2010.

Another important change over the last three decades

affecting household wealth was a major

overhaul of the private pension system in the United States.

As documented in Wolff (2011b), in

1989, 46 percent of all households reported holding a

defined benefit (DB) pension plan. DB plans are

traditional pensions, such as provided by many large

corporations, the federal government, and state

and local governments, which guarantee a steady flow of

income upon retirement. By 2007, that figure

was down to 34 percent. The decline was more pronounced

among younger households, under the age

of 46, from 38 to 23 percent, as well as among middle-aged

households, ages 47 to 64, from 57 to 39

percent.

Many of these plans were replaced by so-called defined

contribution (DC) pension accounts,

most notably 401(k) plans and Individual Retirement accounts

(IRAs). These plans allow household to

accumulate savings for retirement purposes directly. The

share of all household with a DC plan

skyrocketed from 24 percent in 1989 to 53 percent in 2007.

Among younger households, the share rose

from 31 to 50 percent, and among middle-aged households it

went from 28 to 64 percent.

This transformation is even more notable in terms of actual

dollar values. While the average

value of DB pension wealth among all households crept up by

8 percent from $56,500 in 1989 to

$61,200 in 2007, the average value of DC plans shot up more

than 7-fold from $10,600 to $76,800 (all

figures are in 2007 dollars).9 Among younger households,

average DB wealth actually fell in absolute

terms, while DC wealth rose by a factor of 3.3. Among

middle-aged households, the value of DB

pensions also fell in absolute terms while the value of DC

plans mushroomed by a factor of 6.5.

These changes are important for understanding trends in

household wealth because DB pension

wealth is not included in the measure of marketable

household wealth whereas DC wealth is included

(see Section 3 below). Thus, the substitution of DC wealth

for DB wealth is likely to lead to an

overstatement in the “true” gains in household wealth, since

the displacement in DB wealth is not

captured (see Wolff, 2011b, for more discussion).

The other big story was household debt, particularly that of

the middle class, which

skyrocketed during these years, as we shall see below.

Despite the recession, the relative indebtedness

of American families continued to rise from 2007 to 2010.

What have all these major transformations wrought in terms

of the distribution of household

wealth, particularly over the Great Recession? How have

these changes impacted different

demographic groups, particularly as defined by race,

ethnicity, and age? This is the subject of the

remainder of the paper.

2. Plan of the Paper

The paper focuses mainly on how the middle class fared in

terms of wealth over the years 2007

to 2010 during one of the sharpest declines in stock and

real estate prices. As discussed below, the debt

of the middle class exploded from 1983 to 2007, already

creating a very fragile middle class in the

United States. The main interest here is whether their

position deteriorated even more over the Great

Recession. The paper also investigates trends in wealth

inequality, changes in the racial wealth gap and

wealth differences by age, and trends in homeownership

rates, stock ownership, and mortgage debt.

The period covered spans the years from 1962 to 2010. The

choice of years is dictated by the

availability of survey data on household wealth. By 2010, we

are able to see what the fall-out was from

the financial crisis and associated recession and, in

particular, which groups were impacted the most.

There are six specific issues addressed in the paper. (1)

Did the inequality of household wealth

rise over time, particularly during the Great Recession? (2)

Did median household wealth continue to

advance over time or did it fall? (3) Did the debt of the

middle class increase over time, especially over

the Great Recession? (4) What are the time trends in home

ownership and home equity? (5) What

happened to stock ownership? (6) How did time trends in

average wealth, household debt, the home

ownership rate, home equity, and stock ownership vary among

different racial and ethnic groups and

by age group?

The paper is organized as follows. The next section, Section

3, discusses the measurement of

household wealth and describes the data sources used for

this study. Section 4 presents results on time

trends in median and average wealth holdings, Section 5 on

changes in the concentration of household

wealth, and Section 6 on the composition of household

wealth. In Section 7, I provide an analysis of

the effects of leverage on wealth movements over time,

particularly over the Great Recession. Section

8 investigates changes in wealth holdings by race and

ethnicity; and Section 9 reports on changes in

the age-wealth profile. A summary and concluding remarks are

provided in Section 10.

Previous work of mine (see Wolff, 1994, 1998, 2002a, and

2011a), using SCF data from 1983

to 2007, presented evidence of sharply increasing household

wealth inequality between 1983 and 1989

followed by little change between 1989 and 2007. Both mean

and median wealth holdings climbed

briskly during the 1983-1989 period as well as from 1989 to

2007. However, most of the wealth gains

from 1983 to 2007 were concentrated among the richest 20

percent of households. Moreover, despite

the buoyant economy over the 1990s and 2000s, overall

indebtedness continued to rise among

American families.

The ratio of mean wealth between African-American and white

families was very low in 1983,

at 0.19 and about the same in 2007. In 1983, the richest

households were those headed by persons

between 45 and 74 years of age, and the relative wealth

holdings of both younger and older families

fell between 1983 and 2007, particularly those of the

former.

In this study, I look at wealth trends from 1962 to 2010.

The most telling finding is that median

wealth plummeted over the years 2007 to 2010, and by 2010

was at its lowest level since 1969. The

inequality of net worth, after almost two decades of little

movement, was up sharply between 2007 and

2010. Relative indebtedness continued to expand during the

late 2000s, particularly for the middle

class, though the proximate causes were declining net worth

and income rather than an increase in

absolute indebtedness. In fact, the average debt of the

middle class in real terms was down by 25

percent. The sharp fall in median net worth and the rise in

its inequality in the late 2000s are traceable

to the high leverage of middle class families in 2007 and

the high share of homes in their portfolio.

The racial and ethnic disparity in wealth holdings widened

considerably in the years between 2007 and

2010. Hispanics, in particular, got hammered by the Great

Recession in terms of net worth and net

equity in their homes. Finally, young households (under age

45) also got pummeled by the Great

Recession, as their relative and absolute wealth declined

sharply from 2007 to 2010.

3. Data sources and methods

The primary data sources used for this study are the 1983,

1989, 1992, 1995, 1998, 2001, 2004,

2007, and 2010 SCF conducted by the Federal Reserve Board.

Each survey consists of a core

representative sample combined with a high-income

supplement. The high income supplement was

selected as a list sample derived from tax data from the IRS

Statistics of Income. This second sample

was designed to disproportionately select families that were

likely to be relatively wealthy (see, for

example, Kennickell, 2001, for a diiscussion of the design

of the list sample in the 2001 SCF). The

advantage of the high-income supplement is that it provides

a much "richer" sample of high income

and therefore potentially very wealthy families. Typically,

about two thirds of the cases come from the

representative sample and one third from the high-income

supplement. In the 2007 SCF the standard

multi-stage area-probability sample contributed 2,915 cases

while the high-income supplement

contributed another 1,507 cases.

The principal wealth concept used here is marketable wealth

(or net worth), which is defined as

the current value of all marketable or fungible assets less

the current value of debts. Net worth is thus

the difference in value between total assets and total

liabilities or debt. Total assets are defined as the

sum of: (1) owner-occupied housing; (2) other real estate;

(3) demand deposits; (4) time and savings

deposits, certificates of deposit, and money market

accounts; (5) government, corporate, and foreign

bonds and other financial securities; (6) the cash surrender

value of life insurance plans; (7) the cash

surrender value of pension plans, including IRAs, Keogh, and

401(k) plans; (8) corporate stock and

mutual funds; (9) net equity in unincorporated businesses;

and (10) equity in trust funds. Total

liabilities are the sum of: (1) mortgage debt, (2) consumer

debt, including auto loans, and (3) other

debt such as educational loans.

This measure reflects wealth as a store of value and

therefore a source of potential

consumption. I believe that this is the concept that best

reflects the level of well-being associated with

a family's holdings. Thus, only assets that can be readily

converted to cash (that is, "fungible" ones) are

included. As a result, consumer durables such as

automobiles, televisions, and furniture, are excluded

here, since these items are not easily marketed, with the

possible exception of vehicles, or their resale

value typically far understates the value of their

consumption services to the household. Another

justification for their exclusion is that this treatment is

consistent with the national accounts, where

purchase of vehicles is counted as expenditures, not

savings.10 As a result, my estimates of household

wealth will differ from those provided by the Federal

Reserve Board, which includes the value of

vehicles in their standard definition of household wealth

(see, for example, Kennickell and Woodburn,

1999).

Also excluded is the value of future Social Security

benefits the family may receive upon

retirement (usually referred to as "Social Security

wealth"), as well as the value of retirement benefits

from private pension plans ("pension wealth"). Even though

these funds are a source of future income

to families, they are not in their direct control and cannot

be marketed.11

Two other data sources are used in the study. The first of

these is the 1962 Survey of Financial

Characteristics of Consumers (SFCC), also conducted by the

Federal Reserve Board (see Projector and

Weiss, 1966). This is also a stratified sample which

over-samples high income households. Though the

sample design and questionnaire are different from the SCF,

the methodology is sufficiently similar to

allow comparisons with the SCF data (see Wolff, 1987, for

details on the adjustments). The second is a

synthetic dataset, the 1969 MESP database. A statistical

matching technique was employed to assign

income tax returns for 1969 to households in the 1970 Census

of Population. Property income flows

(such as dividends) in the tax data were then capitalized

into corresponding asset values (such as

stocks) to obtain estimates of household wealth (see Wolff,

1980, for details).

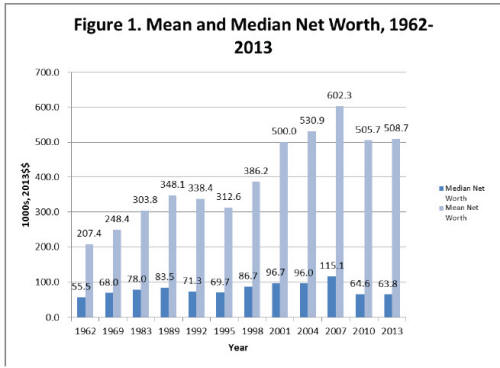

4. Median wealth plummets over the late 2000s

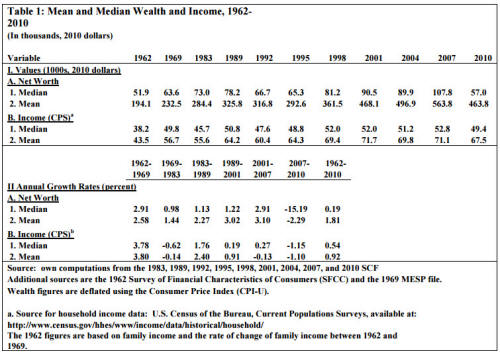

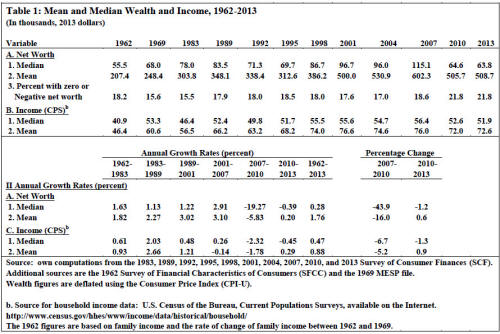

Table 1 documents a robust growth in wealth from 1983 to

2007, even back to 1962. From

1962 to 1983, median wealth in real terms increased at an

annual rate of 1.63 percent. Median wealth

then grew slightly faster between 1989 and 2001, 1.32

percent per year, than between 1983 and 1989,

at 1.13 percent per year. Over the 2001-2007 period it

increased by 19 percent or an annual rate of 2.91

percent, even faster than during the 1970s, 1980s, and

1990s, though comparable to the 1960s. Then

between 2007 and 2010, median wealth plunged by a staggering

47 percent! Indeed, median wealth

was actually lower in 2010 than in 1969 (in real terms). The

primary reasons, as we shall see below,

were the collapse in the housing market and the high

leverage of middle class families.12

Mean net worth also grew vigorously from 1962 to 1983, at an

annual rate of 1.82 percent.

Mean wealth grew quite a bit faster between 1989 and 2001,

at 3.02 percent per year, than from 1983

to 1989, at 2.27 percent per year. There was then a slight

increase in wealth growth from 2001 to 2007

to 3.10 percent per year. This modest acceleration was due

largely to the rapid increase in housing

prices counterbalanced by the reduced growth in stock prices

between 2001 and 2007 in comparison to

1989 to 2001, and to the fact that housing comprised 28

percent and (total) stocks made up 25 percent

of total assets in 2001. Another point of note is that mean

wealth grew more about twice as fast as the

median between 1983 and 2007, indicating widening inequality

of wealth over these years.

The great Recession also saw an absolute decline in mean

household wealth. However, whereas

median wealth plunged by 47 percent, mean wealth fell by

(only) 18 percent.13 In this case, both

falling housing and stock prices were the main causes (see

below). However, here, too, the relatively

faster growth in mean wealth than median wealth (that is,

the latter’s more moderate decline) was

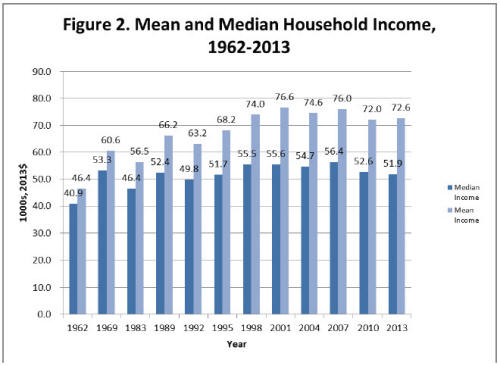

coincident with rising wealth inequality. Median household income in

real terms, based on the Current Population Survey (CPS),

advanced at a fairly solid pace from 1962 to 1983, at 0.85

percent per year. Then, after gaining 11

percent between 1983 and 1989, it grew by only 2.3 percent

from 1989 to 2001 and another 1.6 percent

from 2001 to 2007. From 2007 to 2010, it fell off by 6.4

percent. This reduction was not nearly as

great as that in median wealth. Mean income, after advancing

at an annual rate of 1.2 percent from

1962 to 1983, surged by 2.4 percent per year from 1983 to

1989, advanced by 0.9 percent per year

from 1989 to 2001, and then dipped by -0.1 percent per year

from 2001 to 2007. Mean income also

dropped in real terms from 2007 to 2010, by 5.0 percent,

slightly less than that of median income.

In sum, while median household income virtually stagnated

for the average American

household over the 1990s and 2000s, median net worth grew

strongly over this period. From 2001 to

2007, mean and median income changed very little while mean

and median net worth grew strongly.

The Great Recession, on the other hand, saw a massive

reduction in median net worth but much more

modest declines in mean wealth and both median and mean

income.

5. Wealth inequality jumps in the late 2000s

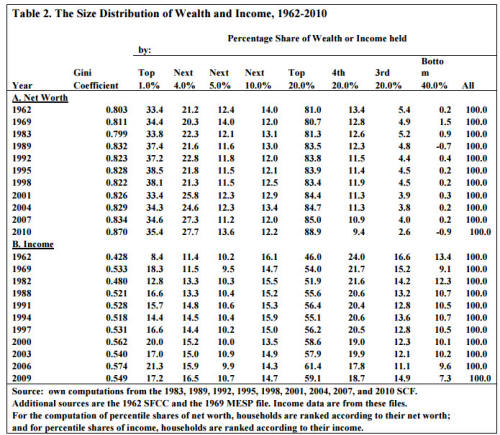

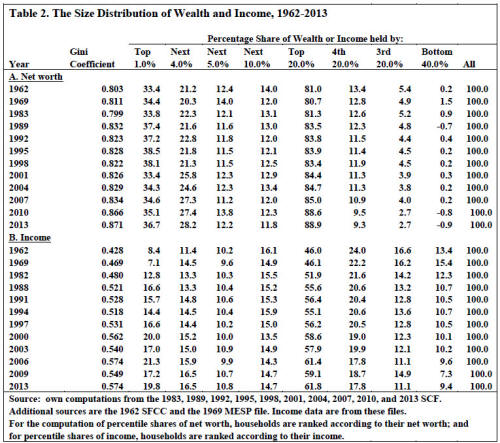

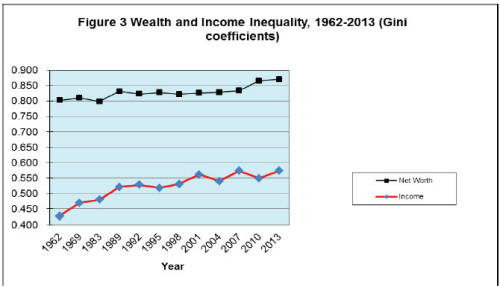

The figures in Table 2 also show that wealth inequality in

1983 was quite close to its level in

1962. Then, after rising steeply between 1983 and 1989, it

remained virtually unchanged from 1989 to

2007. The share of wealth held by the top 1 percent rose by

3.6 percentage points from 1983 to 1989

and the Gini coefficient increased from 0.80 to 0.83. What

was behind the sharp rise in wealth

inequality? There are two principal factors accounting for

changes in wealth concentration (also see

Section 8). The first is the change in income inequality and

the second is the change in the ratio of

stock prices to housing prices. As we shall see below, there

was a huge increase in income inequality

between 1983 and 1989, with the Gini coefficient rising by

0.041 points. Second, stock prices

increased much faster than housing prices. The stock market

boomed and the S&P 50 Index in real

terms was up by 62 percent, whereas median home prices

increased by a mere two percent in real

terms. As a result, the ratio between the two climbed by 58

percent.

Between 1989 and 2007, the share of the top percentile

actually declined sharply, from 37.4 to

34.6 percent, though this was more than compensated for by

an increase in the share of the next four

percentiles. As a result, the share of the top five percent

increased from 58.9 percent in 1989 to 61.8

percent in 2007, and the share of the top quintile rose from

83.5 to 85.0 percent.14 The share of the

fourth and middle quintiles each declined by about a

percentage point from 1989 to 2007, while that of

the bottom 40 percent increased by almost one percentage

point. Overall, the Gini coefficient was

virtually unchanged -- 0.832 in 1989 and 0.834 in 2007. 15

In contrast, the years of the Great Recession saw a very

sharp elevation in wealth inequality,

with the Gini coefficient rising from 0.83 to 0.87.

Interestingly, the share of the top percentile showed

less than a one percentage point gain.16 Most of the rise in

wealth share took place in the remainder of

the top quintile, and overall the share of wealth held by

the top quintile climbed by almost four

percentage points. The shares of the other quintiles,

correspondingly, dropped, with the share of the

bottom 20 percent falling from 0.2 percent to -0.9 percent.

The top 1 percent of families (as ranked by income on the

basis of the SCF data) earned

17 percent of total household income in 2009 and the top 20

percent accounted for 59 percent -- large

figures but lower than the corresponding wealth shares.17

The time trend for income inequality also

contrasts with that for wealth inequality. Income inequality

showed a sharp rise from 1961 to 1982,

with the Gini coefficient expanding from 0.428 to 0.480 and

the share of the top one percent from 8.4

to 12.8 percent.18 Income inequality increased sharply again

between 1982 and 1988, with the Gini

coefficient rising from 0.48 to 0.52 and the share of the

top one percent from 12.8 to 16.6 percent.

There was then very little change between 1988 and 1997.

However, between 1997 and 2000, income

inequality again surged, with the share of the top

percentile rising by 3.4 percentage points, the shares

of the other quintiles falling again, and the Gini index

advancing from 0.53 to 0.56.19 This was

followed by a modest uptick in income inequality, with the

Gini coefficient advancing from 0.562 in

2000 to 0.574 in 2006. All in all, years 2001 to 2007

witnessed moderate rises in both wealth and

income inequality.

Perhaps, somewhat surprisingly, the Great Recession

witnessed a rather sharp contraction in

income inequality. The Gini coefficient fell from 0.574 to

0.549 and the share of the top one percent

dropped sharply from 21.3 to 17.2 percent. Property income

and realized capital gains (which is

included in the SCF definition of income), as well as

corporate bonuses and the value of stock options,

plummeted over these years, a process which explains the

steep decline in the share of the top

percentile. Real wages, as noted above, actually rose over

these years, though the unemployment rate

also increased. As a result, the income of the middle class

was down but not nearly as much in

percentage terms as that of the high income groups. In

contrast, transfer income such as unemployment

insurance rose, so that the bottom also did better in

relative terms than the top. As a result, overall

income inequality fell over the years 2006 to 2009.20 One of

the puzzles we have to contend with is the

fact wealth inequality rose sharply over the Great Recession

while income inequality fell sharply. I

will return to this question in Section 8 below.

5.1 The share of overall wealth gains, 1983 to 2010

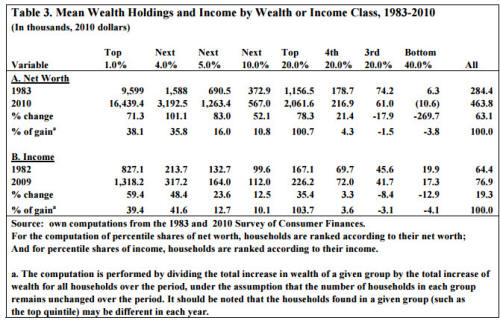

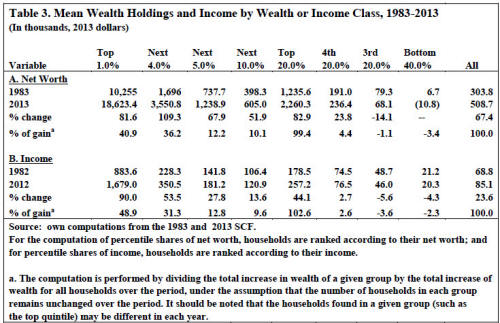

Over the years 1983 to 2010, is period, the largest gains in

wealth and income in relative terms

were made by the wealthiest households (see Table 3). The

top one percent saw their average wealth

(in 2010 dollars) rise by 71 percent. The remaining part of

the top quintile experienced increases from

52 to 101 percent and the fourth quintile by 21 percent,

while the middle quintile lost 18 percent and

the poorest 40 percent lost 270 percent!

Another way of viewing this phenomenon is afforded by

calculating the proportion of the total

increase in real household wealth between 1983 and 2010

accruing to different wealth groups. This is

computed by dividing the increase in total wealth of each

percentile group by the total increase in

household wealth, while holding constant the number of

households in that group. If a group's wealth

share remains constant over time, then the percentage of the

total wealth growth received by that group

will equal its share of total wealth. If a group's share of

total wealth increases (decreases) over time,

then it will receive a percentage of the total wealth gain

greater (less) than its share in either year.

However, it should be noted that in these calculations, the

households found in a given group may be

different in the two years.

The results indicate that the richest one percent received

over 38 percent of the total gain in

marketable wealth over the period from 1983 to 2010. This

proportion was greater than the share of

wealth held by the top one percent in any of the 9 years.

The next 4 percent received 36 percent of the

total gain and the next 15 percent 27 percent, so that the

top quintile collectively accounted for a little

over 100 percent of the total growth in wealth.

A similar calculation using the SCF income data reveals that

the greatest gains in real income

over the period from 1982 to 2009 were made by households in

the top one percent of the income

distribution, who saw their incomes grow by 59 percent. Mean

incomes increased by almost half for

the next 4 percent, over a quarter for the next highest 5

percent and by 13 percent for the next highest

ten percent. The fourth quintile of the income distribution

experienced only a 3 percent growth in

income, while the middle quintile and the bottom 40 percent

had absolute declines in mean income. Of

the total growth in real income between 1982 and 2009, 39

percent accrued to the top one percent and

over 100 percent to the top quintile. These figures are very

close to those for wealth.

These results indicate rather dramatically that the growth

in the economy during the period

from 1983 to 2010 was concentrated in a surprisingly small

part of the population -- the top 20 percent

and particularly the top one percent.

6. Household debt continues to remain high

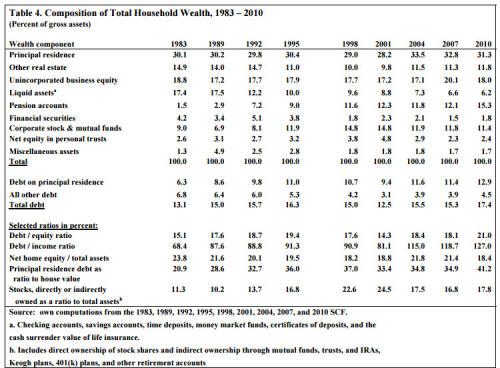

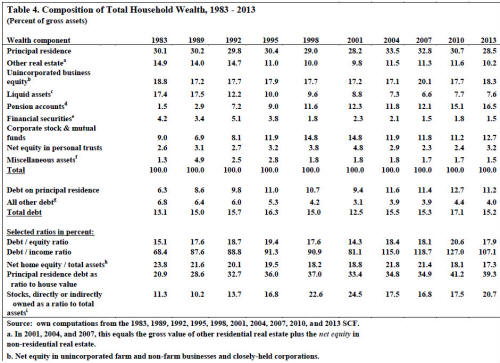

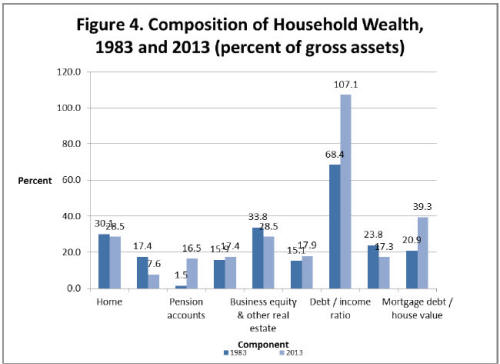

In 2010, owner-occupied housing accounted for 31 percent of

total assets (see Table 4).

However, net home equity -- the value of the house minus any

outstanding mortgage -- amounted to

only 18 percent of total assets. Real estate, other than

owner-occupied housing, comprised 12 percent,

and business equity another 18 percent. Liquid assets

(demand and time deposits, money market funds,

CDs, and the cash surrender value of life insurance) made up

6 percent and pension accounts 15

percent. Bonds and other financial securities amounted to 2

percent; corporate stock, including mutual

funds, to 11 percent; and trust equity to 2 percent. Debt as

a proportion of gross assets was 17 percent,

and the debt-equity ratio (the ratio of household debt to

net worth) was 0.21.

There were some significant changes in the composition of

household wealth over the years

1983 to 2010. First, the share of gross housing wealth in

total assets, after fluctuating between 28.2 and

30.4 percent from 1983 to 2001, increased to 32.8 percent in

2007 and then fell to 31.3 percent in

2010. There are two main factors behind this – the

homeownership rate and housing prices. According

to the SCF, the homeownership rate, after falling from 63.4

percent in 1983 to 62.8 percent in 1989,

picked up to 67.7 percent in 2001 and 68.6 percent in 2007

but then fell to 67.2 percent in 2010.

Median house prices for existing homes rose by 19 percent in

real terms between 2001 and 2007 but

then plunged by 26 percent from 2007 to 2010. A substantial

share of the movement of the proportion

of housing in gross assets can be traced to these two time

trends.21

Second, net equity in owner-occupied housing as a share of

total assets, after falling from 24

percent in 1983 to 19 percent in 2001, rose to 21 percent in

2007 but then fell sharply to 18 percent in

2010. The difference between gross and net housing as a

share of total assets can be traced to the

changing magnitude of mortgage debt on homeowner's property,

which increased from 21 percent in

1983 to 33 percent in 2001, 35 percent in 2007 and then 41

percent in 2010. Moreover, mortgage debt

on principal residence climbed from 9.4 to 11.4 percent of

total assets between 2001 and 2007 and then

to 12.9 percent in 2010. The sharp decline in net home

equity as a proportion of from 2007 to 2010 is

attributable to the sharp decline in housing prices.

Third, relative indebtedness increased, with the debt-equity

(net worth) ratio climbing from 15

percent in 1983 to 18 percent in 2007 and then to 21 percent

in 2010. Likewise, the ratio of debt to

total income surged from 68 percent in 1983 to 119 percent

in 2007 and then to 127 percent in 2010,

its high for this period. If mortgage debt on principal

residence is excluded, the ratio of other debt to

total assets actually fell off from 6.8 percent in 1983 to

3.9 percent in 2007 but then rose slightly to 4.5

percent in 2010. The large rise in relative indebtedness

between 2007 and 2010 could be due to a

rise in the absolute level of debt and/or a fall off in net

worth and income. As shown in Table 1, both

mean net worth and mean income fell over the three years.

There was also a slight contraction of debt

in constant dollars, with mortgage debt declining by 5.0

percent, other debt by 2.6 percent, and total

debt by 4.4 percent. Thus, the steep rise in the debt to

equity and the debt to income ratio over the three

years was entirely due to the reduction in wealth and

income.

A fourth change is a dramatic increase in pension accounts,

which rose from 1.5 percent of

total assets in 1983 to 12 percent in 2007 and then to 15

percent in 2010. There was a huge increase in

the share of households holding these accounts between 1983

and 2001, from 11 to 52 percent. The

mean value of these plans in real terms climbed

dramatically. It almost tripled among account holders

and skyrocketed by a factor of 13.6 among all households.

These time trends partially reflect the

history of DC plans. IRAs were first established in 1974.

This was followed by 401(k) plans in 1978

for profit-making companies (403(b) plans for non-profits

are much older). However, 401(k) plans the

like did not become widely available in the workplace until

about 1989.

From 2001 to 2007 the share of households with a DC plan

leveled off and then from 2007 to

2010 the share fell modestly, from 52.6 to 50.4 percent. The

average value of DC plans in constant

dollars continued to grow after 2001. Overall, it advanced

by 21 percent from 2001 to 2007 and then

by 11 percent from 2007 to 2010 among account holders and by

22 percent and 7 percent, respectively,

among all households. Thus, despite the stock market

collapse of 2007-2010 and the 18 percent decline

of overall mean net worth, the average value of DC accounts

continued to grow after 2007. The reason

is that households shifted their portfolio out of other

assets and into DC accounts.

Fifth, the share of corporate stock and mutual funds in

total assets rose rather briskly from 9

percent in 1983 to 15 percent in 2001, and then plummeted to

12 percent in 2007 and even further to

11 percent in 2010. If we include the value of stocks

indirectly owned through mutual funds, trusts,

IRAs, 401(k) plans, and other retirement accounts, then the

value of total stocks owned as a share of

total assets more than doubled from 11 percent in 1983 to 25

percent in 2001, tumbled to 17 percent in

2007, and then rose slightly to 18 percent in 2010. The rise

during the 1990s reflected the bull market

in corporate equities as well as increased stock ownership,

while the decline in the 2000s was a result

of the sluggish stock market as well as a drop in stock

ownership.

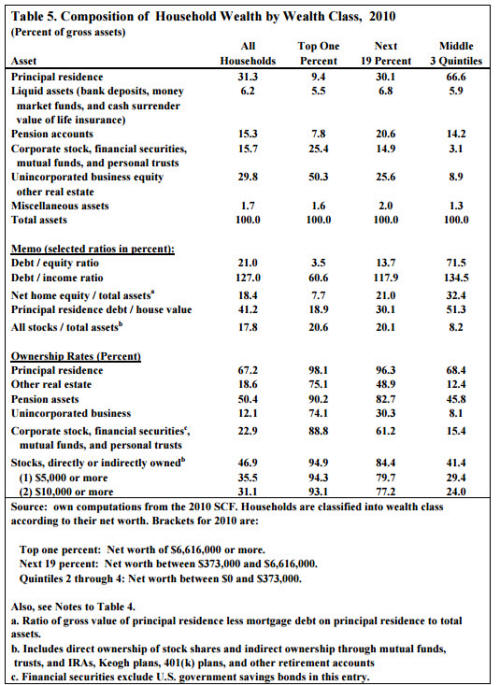

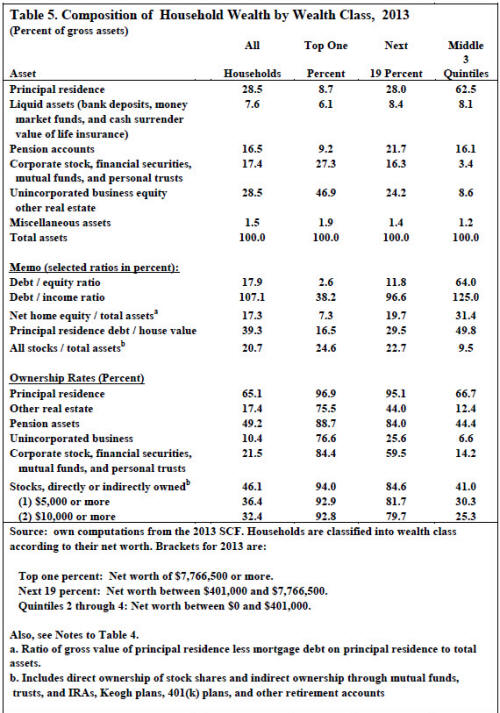

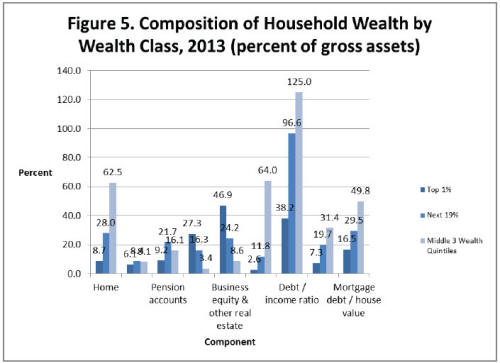

6.1 Portfolio composition by wealth class

The tabulation in Table 4 provides a picture of the average

holdings of all families in the

economy, but there are marked class differences in how

middle-class families and the rich invest their

wealth. As shown in Table 5, the richest one percent of

households (as ranked by wealth) invested over

three quarters of their savings in investment real estate,

businesses, corporate stock, and financial

securities in 2010. Corporate stocks, either directly or

indirectly owned, comprised 21 percent.

Housing accounted for only 9 percent of their wealth, liquid

assets 5 percent, and pension accounts 8

percent. The debt-equity ratio was only 3 percent, the ratio

of debt to income was 61 percent, and the

ratio of mortgage debt to house value was 19 percent.

Among the next richest 19 percent of U.S. households,

housing comprised 30 percent of their

total assets, liquid assets 7 percent, and pension assets 21

percent. Investment assets – non-home real

estate, business equity, stocks, and bonds – made up 41

percent and 20 percent was in the form of

stocks directly or indirectly owned. Debt amounted to 14

percent of their net worth and 118 percent of

their income, and the ratio of mortgage debt to house value

was 30 percent.

In contrast, almost exactly two thirds of the wealth of the

middle three quintiles of households

was invested in their own home in 2010. However, home equity

amounted to only 32 percent of total

assets, a reflection of their large mortgage debt. Another

20 percent went into monetary savings of one

form or another and pension accounts. Together housing,

liquid assets, and pension assets accounted

for 87 percent of total assets, with the remainder in

investment assets. Stocks directly or indirectly

owned amounted to only 8 percent of their total assets. The

debt-equity ratio was 0.72, substantially

higher than that for the richest 20 percent, and their ratio

of debt to income was 135 percent, also much

higher than that of the top quintile. Finally, their

mortgage debt amounted to a little more than half the

value of their principal residences.

Almost all households among the top 20 percent of wealth

holders owned their own home, in

comparison to 68 percent of households in the middle three

quintiles. Three-quarters of very rich

households (in the top percentile) owned some other form of

real estate, compared to 49 percent of rich

households (those in the next 19 percent of the

distribution) and only 12 percent of households in the

middle 60 percent. Eighty-nine percent of the very rich

owned some form of pension asset, compared

to 83 percent of the rich and 46 percent of the middle. A

somewhat startling 74 percent of the very rich

reported owning their own business. The comparable figures

are 30 percent among the rich and only 8

percent of the middle class.

Among the very rich, 89 percent held corporate stock, mutual

funds, financial securities or a

trust fund, in comparison to 61 percent of the rich and only

15 percent of the middle. Ninety-five

percent of the very rich reported owning stock either

directly or indirectly, compared to 84 percent of

the rich and 41 percent of the middle. If we exclude small

holdings of stock, then the ownership rates

drop off sharply among the middle three quintiles, from 41

percent to 29 percent for stocks worth

$5,000 or more and to 24 percent for stocks worth $10,000 or

more.

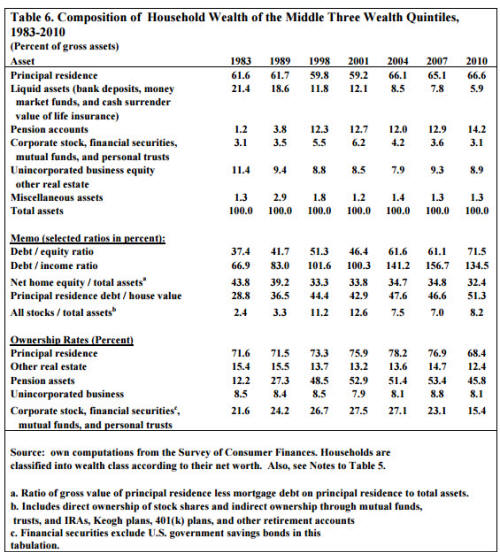

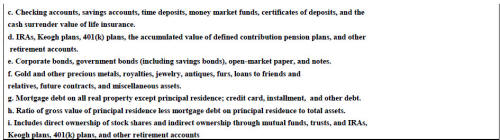

The rather staggering debt level of the middle class in 2010

raises the question of whether this

is a recent phenomenon or whether it has been going on for

some time. Table 6 shows the wealth

composition for the middle three wealth quintiles from 1983

to 2010. Houses as a share of assets

remained virtually unchanged from 1983 to 2001 but then

increased from 2001 to 2010. It might seem

surprising that despite the steep drop in home prices from

2007 to 2010, housing as a share of total

assets actually increased slightly. The reason is that the

other components of wealth fell even more

than housing. While housing fell by 30 percent in real

terms, other real estate was down by 39 percent,

liquid assets by 48 percent, and stocks and mutual funds by

47 percent.

Pension accounts rose as a share of total assets by almost

13 percentage points from 1983 to

2010 while liquid assets declined as a share by 16

percentage points. This set of changes paralleled that

of all households. The share of all stocks in total assets

mushroomed from 2.4 percent in 1983 to 12.6

percent in 2001 and then fell off to 8.2 percent in 2010 as

stock prices stagnated and then collapsed

and middle class households divested themselves of stock

holdings. The proportion of middle class

households with a pension account surged by 41 percentage

points between 1983 and 2007 but then

fell off sharply by almost 8 percentage points in 2010.

Changes in debt, however, represent the most dramatic

movements. There was a sharp rise in

the debt-equity ratio of the middle class from 0.37 in 1983

to 0.61 in 2007, with all of the increase

occurring between 2001 and 2004, a reflections mainly of a

steep rise in mortgage debt. The debt to

income ratio more than doubled from 1983 to 2007. Once,

again, much of the increase happened

between 2001 and 2004. The rise in the debt-equity ratio and

the debt to income ratio was much

steeper than for all households. In 1983, for example, the

debt to income ratio was about the same for

middle class as for all households but by 2007 the ratio was

much larger for the middle class.

Then, the Great Recession hit. The debt-equity ratio

continued to rise, reaching 0.72 in 2010

but there was actually a retrenchment in the debt to income

ratio, falling to 1.35 in 2010. The reason is

that from 2007 to 2010, the mean debt of the middle class in

constant dollars actually contracted by 25

percent. There was, in fact, a 23 percent reduction in

mortgage debt as families paid down their

outstanding balances, and an even larger drop in other debt

of 32 percent as families paid off credit

card balances and other forms of consumer debt. The steep

rise in the debt-equity ratio of the middle

class between 2007 and 2010 was due to the sharp drop in net

worth, while the decline in the debt to

income ratio was almost exclusively due to the sharp

contraction of overall debt.

As for all households, the ratio of net home equity to

assets fell for the middle class from 1983

to 2010 and mortgage debt as a proportion of house value

rose. The decline in the ratio of net home

equity to total assets between 2007 and 2010 was relatively

small despite the steep decrease in home

prices, a reflection of the sharp reduction in mortgage

debt. On the other hand, the rise in the ratio of

mortgage debt to house values was relatively large over

these years because of the fall off in home

prices.

6.2 The “middle class squeeze”

Nowhere is the middle class squeeze more vividly

demonstrated than in their rising debt. As

noted above, the ratio of debt to net worth of the middle

three wealth quintiles rose from 0.37 in 1983 to

0.46 in 2001 and then jumped to 0.61 in 2007.

Correspondingly, their debt to income rose from 0.67 in

1983 to 1.00 in 2001 and then zoomed up to 1.57 in 2007 This

new debt took two major forms. First,

because housing prices went up over these years, families

were able to borrow against the now enhanced

value of their homes by refinancing their mortgages and by

taking out home equity loans. In fact,

mortgage debt on owner-occupied housing (principal residence

only) as a proportion of total assets

climbed from 29 percent in 1983 to 47 percent in 2007, and

home equity as a share of total assets fell

from 44 to 35 percent over these years. Second, because of

their increased availability, families ran up

huge debt on their credit cards.

Where did the borrowing go? Some have asserted that it went

to invest in stocks. However, if this

were the case, then stocks as a share of total assets would

have increased over this period, which it did

not (it fell from 13 to 7 percent between 2001 and 2007).

Moreover, they did not go into other assets. In

fact, the rise in housing prices almost fully explains the

increase in the net worth of the middle class from

2001 to 2007. Of the $16,400 rise in median wealth, gains in

housing prices alone accounted for $14,000

or 86 percent of the growth in wealth. Instead, it appears

that middle class households, experiencing

stagnating incomes, expanded their debt in order to finance

normal consumption expenditures.

The large build-up of debt set the stage for the financial

crisis of 2007 and the ensuing Great

Recession. When the housing market collapsed in 2007, many

households found themselves

“underwater,” with larger mortgage debt than the value of

their home. This factor, coupled with the loss

of income emanating from the recession, led many home owners

to stop paying off their mortgage debt.

The resulting foreclosures led, in turn, to steep reductions

in the value of mortgage-backed securities.

Banks and other financial institutions holding such assets

experienced a large decline in their equity,

which touched off the financial crisis.

7. The role of leverage in explaining the steep fall in

median wealth and the sharp rise in wealth

inequality over the Great Recession

Two major puzzles emerge from the preceding analysis. The

first is the steep plunge in median

net worth between 2007 and 2010 of 47 percent. This happened

despite a moderate drop in median

income of 6.4 percent in real terms and steep but less steep

declines in housing and stock prices of 24

and 26 percent in real terms, respectively.

The second is the steep increase of wealth inequality of

0.035 Gini points. It is surprising that

wealth inequality rose so sharply, given that income

inequality dropped by 0.025 Gini points (at least

according to the SCF data) and the ratio of stock prices to

housing prices was essentially unchanged. In

fact, as shown in Wolff (2002), wealth inequality is

positively related to the ratio of stock to house

prices, since the former is heavily concentrated among the

rich and the latter is the chief asset of the

middle class. A regression run of the share of wealth held

by the top one percent of households

(WLTH) on the share of income received by the top five

percent of families (INC), and the ratio of the

Standard and Poor 500 index to housing prices (RATIO), with

21 data points between 1922 and 1998,

yields:

(1) WLTH = 5.10 + 1.27 INC + 0.26 RATIO, R2 = 0.64, N = 21

(0.9) (4.2) (2.5)

with t-ratios shown in parentheses. Both variables are

statistically significant (INC at the 1 percent

level and RATIO at the 5 percent level) and with the

expected (positive) sign. Also, the fit is quite

good, even for this simple model.

Changes in median wealth and wealth inequality from 2007 to

2010 can be explained to a large

extent by leverage (the ratio of debt to net worth). The

steep fall in median wealth was due in large

measure to the high leverage of middle class households. The

spike in wealth inequality was largely

due to differential leverage between the rich and the middle

class.

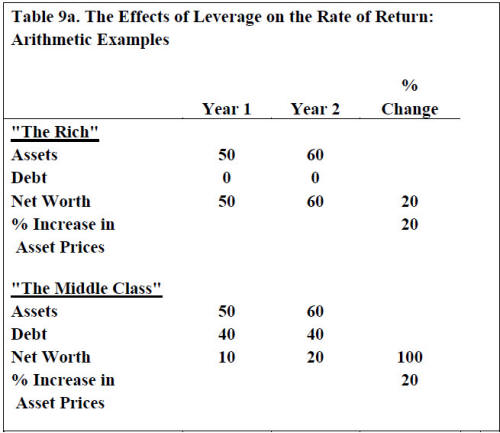

7.1 Two arithmetic examples

A simple arithmetical example might illustrate the effects

of leverage. Suppose average assets

are 50 and average debt is zero. Also, suppose that asset

prices rise by 20 percent. Then average net

worth also rises by 20 percent. However, now suppose that

average debt is 40 and asset prices once

again rise by 20 percent. Then average net worth increases

from a base of 10 (50 minus 40) to 20 (60

minus 40) or by 100 percent, Thus, leverage amplifies the

effects of asset price changes. However, the

converse is also true. Suppose that asset prices decline by

20 percent. In the first case, net worth falls

from 50 to 40 or by 20 percent. In the second case, net

worth falls from 10 to 0 (40 minus 40) or by

100 percent. Thus, leverage can also magnify the effects of

an asset price bust.

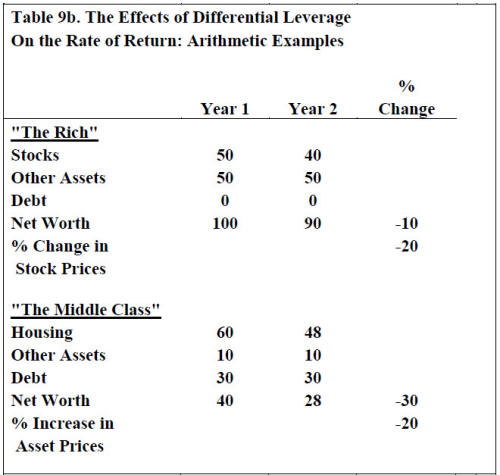

Another arithmetical example can illustrate the effects of

differential leverage. Suppose the

total assets of the very rich in a given year is 100,

consisting of 50 in stocks and 50 in other assets, and

its debt is zero, for a net worth of 100. For the “middle

class”, suppose total assets are 70, consisting of

60 in housing and 10 in other assets, and their debt is 30,

for a net worth of 40. The ratio of net worth

between the very rich and the middle is then 2.5 (100/40).

Suppose the value of both stocks and housing falls by 20

percent but the value of “other assets”

remains unchanged. Then, the total assets of the rich fall

to 90 (40 in stocks and 50 in other), for a net

worth of 90. The total assets of the middle falls to 58 (48

in housing and 10 in other) but its debt

remains unchanged at 30, for a net worth of 28. As a result,

the ratio of net worth between the two

groups rises to 3.21 (90/28). Here it is apparent that even

though housing and stock prices fall at the

same rate, wealth inequality goes up. The reason is

differential leverage between the two groups. If

asset prices decline at the same rate, net worth decreases

at an even greater rate for the middle than the

rich, since the debt-equity ratio is higher for the former

than the latter. The converse is also true. A

proportionate increase in house and stock prices will result

in a decrease in wealth inequality.

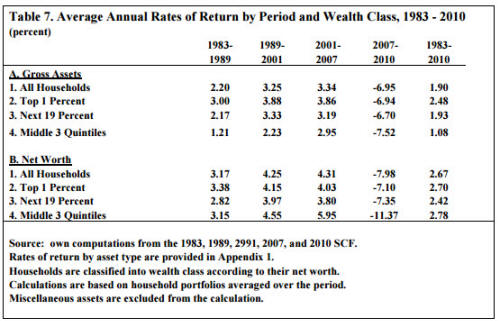

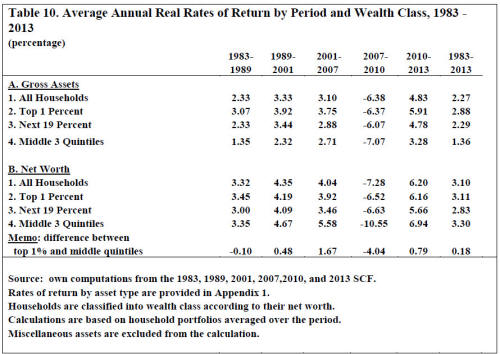

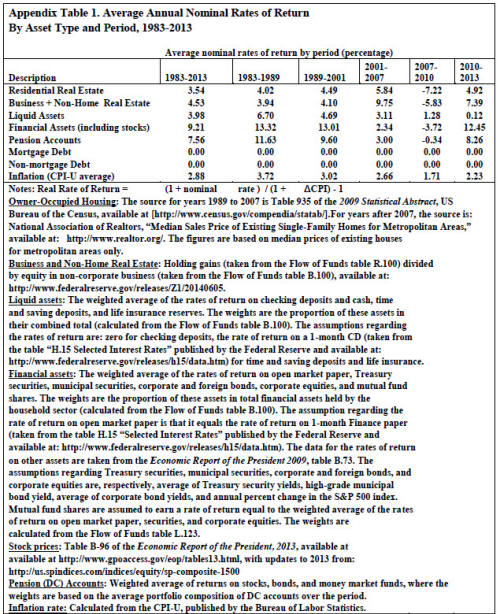

7.2 Rates of return

Table 7 shows estimated average annual rates of return for

both gross assets and net worth over

the period from 1983 to 2010. Results are based on the

average portfolio composition over the period.

It is first of interest to look at the results for all

households . The overall average annual rate of return

on gross assets rose from 2.20 percent in the 1983-1989

period to 3.25 percent in the 1989-2001 period

and then to 3.34 percent in the 2001-2007 period before

plummeting to -6.95 percent over the Great

Recession. The largest declines in asset prices over the

years 2007 to 2010 occurred for residential real

estate and the category businesses and non-home real estate.

The value of financial assets, including

stocks, bonds, and other securities, registered an annual

rate of return of “only” -2.23 percent because

interest rates on corporate and foreign bonds continued to

remain strong over these years. The value of

pension accounts had a -2.46 percent annual rate of return,

reflecting the mixture of bonds and stocks

held in pension accounts.

The average annual rate of return on net worth among all

households also increased from 3.17

percent in the first period to 4.25 percent in the second

and then to 4.31 percent in the third but then

fell off sharply to -7.98 percent in the last period. It is

first of note that the annual rates of return on net

worth are uniformly higher – by about one percentage point –

than those of gross assets over the first

three periods, when asset prices were generally rising.

However, in the 2007-2010 period, the opposite

was the case, with the annual return on net worth 0.44

percent lower than that on gross assets. These

results illustrate the effect of leverage, raising the

return when asset prices rise and lowering the return

when asset prices fall. Over the full 1983-2010 period, the

annual return on net worth was 0.87

percentage points higher than that on gross assets.22

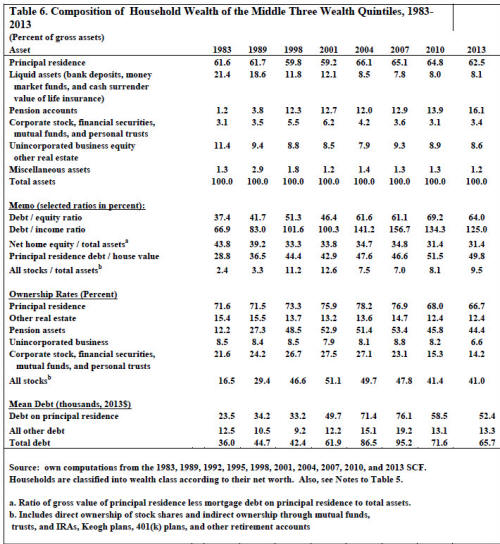

There are striking differences in returns by wealth class.

The highest returns on gross assets

were registered by the top one percent of wealth holders,

followed by the next 19 percent and then by

the middle three wealth quintiles. The one exception was the

2007-2010 period when the next 19

percent was first, followed by the top one percent and then

the middle three quintiles. The differences

are quite substantial. Over the full 1983-2010 period, the

average annual rate of return on gross assets

for the top one percent was 0.55 percentage points greater

than that of the next 19 percent and 1.39

percentage points greater than that of the middle quintiles.

The differences reflect the greater share of

high yield investment assets like stocks in the portfolios

of the rich and the greater share of housing in

the portfolio of the middle class (see Table 5 for details

on portfolio composition).

This pattern is almost exactly reversed for rates of return

for net worth. In this case, in the first

three periods when asset prices were generally rising, the

highest return was recorded by the middle

three wealth quintiles but in the 2007-2010 period, when

asset prices were declining, the middle three

quintiles registered the lowest (that is, most negative)

return. The exception was the first period when

the top one percent had the highest return. The reason was

the substantial spread in returns on gross

assets between the top one percent and the middle three

quintiles – 1.79 percentage points.

Interestingly, returns for the top one percent were greater

than that of the next 19 percent and for the

same reason.

Differences in returns between the top one percent and the

middle three quintiles were quite

substantial in some years. In the 2001-2007 period, the

return on net worth was 5.95 percent per year

for the latter and 4.03 percent per year for the former – a

difference of 1.92 percentage points. Over the

Great Recession the rate of return on net worth was -7.10

percent for the top one percent and,

astonishingly, -11.39 percent for the middle three quintiles

– a differential of 4.27 percentage points.

The spread in rates of return between the top one percent

and the middle three quintiles reflects the

much higher leverage of the middle class. In 2010, for

example, the debt-equity ratio of the middle

three quintiles was 0.72 while that of the top one percent

was 0.04. The debt-equity ratio of the next 19

percent was also relatively low, at 0.14. Indeed, except for

years 2007 to 2010, the rate of return on net

worth for the middle quintiles was more than double its

return on gross assets.

The huge negative rate of return on net worth of the middle

three wealth quintiles was largely

responsible for the precipitous drop in median net worth

between 2007 and 2010. This factor, in turn,

was due to the steep drop in asset prices, particularly

housing, and the very high leverage of the middle

wealth quintiles. Likewise, the very high rate of return on

net worth of the middle three quintiles over

the 2001-2007 period (5.95 percent per year) played a big

role in explaining the robust advance of

median net worth, despite the sluggish growth in median

income. This in turn, was a result of their

high leverage coupled with the boom in housing prices.

The substantial differential in rates of return on net worth

between the middle three wealth

quintiles and the top quintile (over four percentage points)

helps explain why wealth inequality rose

sharply between 2007 and 2010 despite the decline in income

inequality. Likewise this differential

over the 2001-2007 period (a spread of about two percentage

points in favor of the middle quintiles)

helps account for the stasis in wealth inequality over these

years despite the increase in income

inequality.

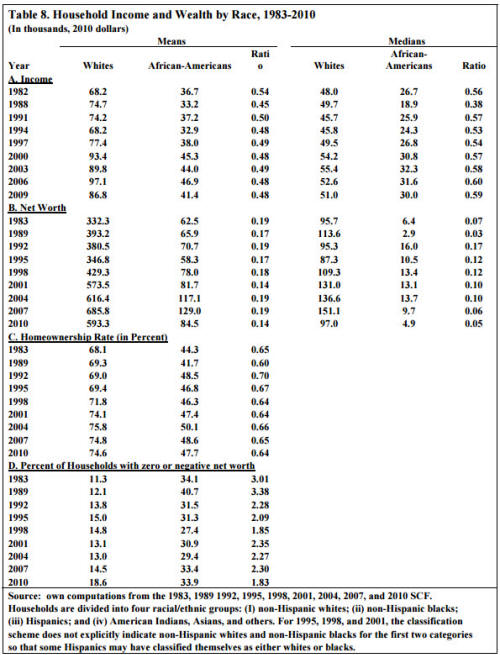

8. The racial divide widens over the Great Recession

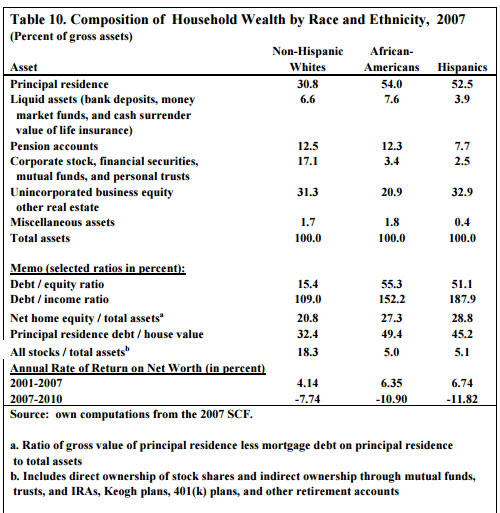

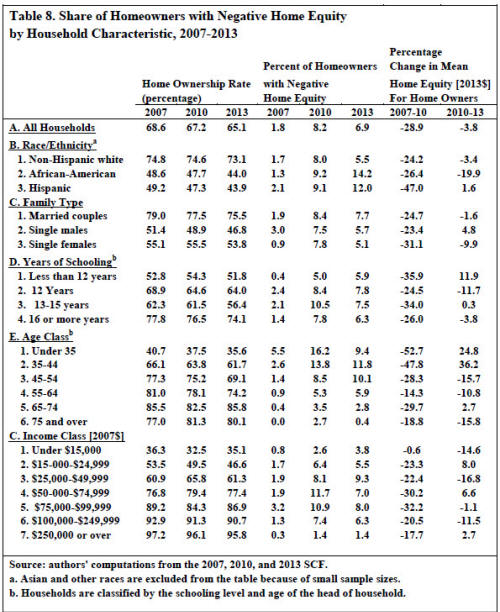

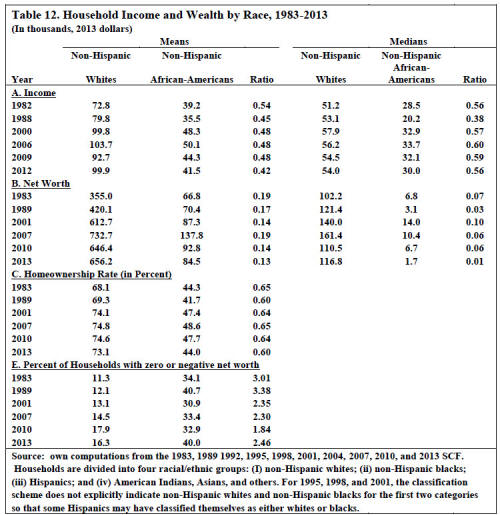

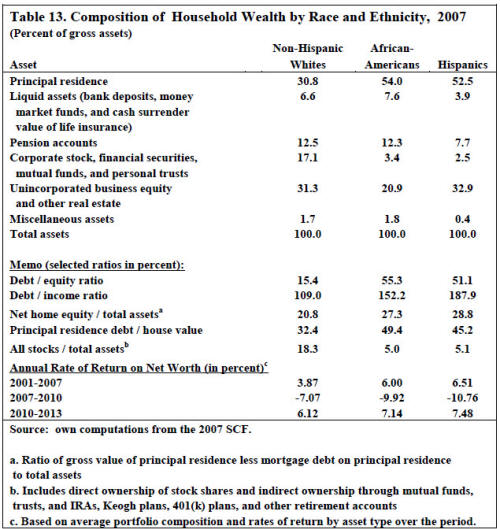

Striking differences are found in the wealth holdings of

different racial and ethnic groups. In

Tables 10 and 11, households are divided into three groups:

(i) non-Hispanic whites (“whites” for

short), (ii) non-Hispanic African-Americans (“blacks” for

short), and (iii) Hispanics.23 In 2007, while

the ratio of mean incomes between white and black households

was an already low 0.48 and the ratio

of median incomes was 0.60, the ratios of mean and median

wealth holdings were even lower, at 0.19

and 0.06, respectively.24 The homeownership rate for black

households was 49% in 2007, a little less

than two thirds that among whites, and the percentage of

black households with zero or negative net

worth stood at 33, more than double that among whites.

Between 1982 and 2006, while the average real income of

white households increased by 42

percent and the median by 10 percent, the former rose by

only 28 percent for black households but the

latter by 18 percent. As a result, the ratio of mean income

slipped from 0.54 in 1982 to 0.48 in 2006,

while the ratio of median income rose from 0.56 to 0.60.25

The contrast in time trends between the

ratio of means and that of medians reflects the huge

increase in income for a relatively small number of

white households – a result of rising income inequality

among whites.

Between 1983 and 2001, average net worth in constant dollars

climbed by 73 percent for

whites but rose by only 31 percent for black households, so

that the net worth ratio fell from 0.19 to

0.14. Most of the slippage occurred between 1998 and 2001,

when white net worth surged by a

spectacular 34 percent and black net worth advanced by only

a respectable 5 percent. Indeed, mean net

worth growth among black households was slightly higher in

the 1998-2001 years, at 1.55 percent per

year, than in the preceding 15 years, at 1.47 percent per

year. However, between 2001 and 2007, mean

net worth among blacks gained an astounding 58 percent while

white wealth advanced by 29 percent,

so that by 2007 the net worth ratio was back to 0.19, the

same level as in 1983.

It is not clear how much of the sharp drop in the racial

wealth gap between 1998 and 2001 and

the turnaround between 2001 and 2007 are due to actual

wealth changes in the African-American

community and how much is due to sampling variability (since

the sample sizes of African Americans

are relatively small in all years). However, one salient

difference between the two groups is the much

higher share of stocks in the white portfolio and the much

higher share of homes in the portfolio of

black households. In 2001, the gross value of principal

residences formed 46 percent of the total assets

of black households, compared to 27 percent among whites,

while (total) stocks were 25 percent of the

total assets of whites and only 15 percent that of black

households. In the case of median wealth, the

black-white ratio fluctuated over time but was almost

exactly the same in 2007 as in 1983, 0.06

compared to 0.07.

The homeownership rate of black households grew from 44 to

47 percent between 1983 and

2001 but relative to white households, the homeownership

rate slipped slightly from 0.65 in 1983 to

0.64 in 2001. From 2001 to 2007, the black homeownership

rate rose slightly from 74.1 to 74.8

percent, and the ratio of homeownership rates advanced

slightly, to 0.65. The percentage of black

households with zero or negative net worth fell from 34

percent in 1983 to 31 percent in 2001 (and

also declined relative to the corresponding rate for

whites). However, in the ensuing six years the share

rose back to 33 percent in 2007 (though relative to white

households remained largely unchanged).

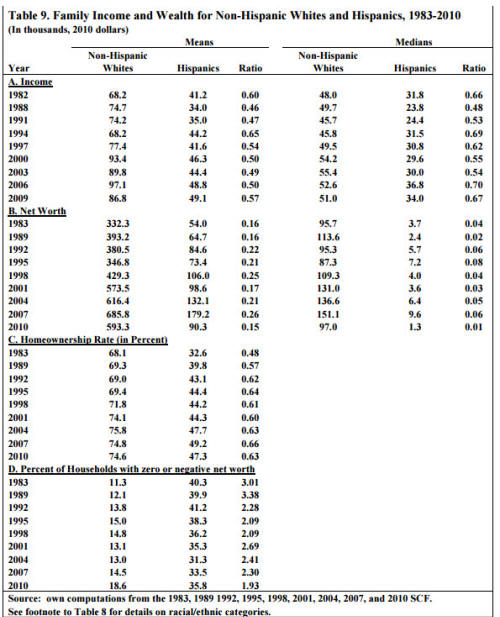

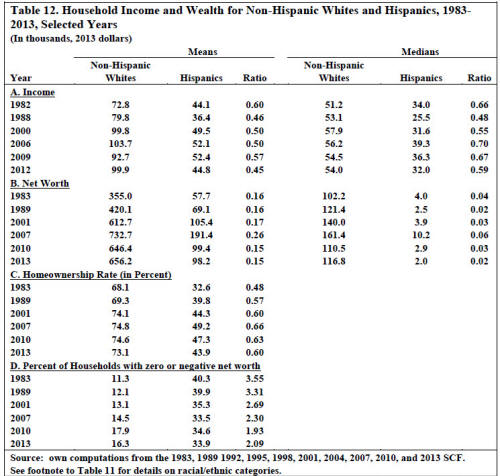

The picture is rather different for Hispanics (see Table 9).

The ratio of mean income between

Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites in 2007 was 0.50, almost

the same as that between black and white

households. However, the ratio of median income was 0.70,

much higher than the ratio between black

and white households. The ratio of mean net worth was 0.26

compared to a ratio of 0.19 between

blacks and whites. However, the ratio of medians was 0.06,

almost identical to that between blacks and

whites. The Hispanic homeownership rate was 49 percent,

almost identical to that of black households,

and 34 percent of Hispanic households reported zero or

negative wealth, almost the same as African-

Americans.

Hispanic households made considerable progress over the

years1983 to 2007. Mean income

grew by 18 percent and median income by 16 percent, so that

while the ratio of mean income slid from

60 to 50 percent, that of median income advanced from 66 to

70 percent. Between 1983 and 2001,

mean wealth doubled for Hispanic households and the ratio of

mean net worth increased slightly from

16 to 17 percent. Mean net worth among Hispanics then

climbed by another 82 percent between 2001

and 2007, and the corresponding ratio advanced to 26

percent, quite a bit higher than that between

black and white households. The surge in Hispanic wealth

from 2001 to 2007 can be traced to a five

percentage point jump in the Hispanic home ownership rate

(see below).

From 1983 to 2007, median wealth among Hispanics remained

largely unchanged, so that the

ratio of median wealth between Hispanics and whites stayed

virtually the same. In contrast, the

homeownership rate among Hispanic households surged from 33

to 44 percent between 1983 and

2001, and the ratio of homeownership rates between the two

groups grew from 0.48 in 1983 to 0.60 in

2001. Between 2001 and 2007, the Hispanic homeownership rose

once again, to 49 percent, about the

same as black households, and the homeownership ratio rose

sharply to 0.66. The percentage of

Hispanic households with zero or negative net worth fell

rather steadily over time, from 40 percent in

1983 to 34 percent in 2007 (about the same as black

households), and the share relative to white

household tumbled from a ratio of 3.0 to 2.3.

Despite some progress from 2001 to 2007, the respective

wealth gaps between minorities and

whites were still much greater than the corresponding income

gaps in 2007. While mean income ratios

were of the order of 50 percent, mean wealth ratios were of

the order of 20-25 percent and the share

with zero or negative net worth was around a third, in

contrast to 15 percent among non-Hispanic

white households (a difference that appears to mirror the

gap in poverty rates). While blacks and

Hispanics were left out of the wealth surge of the years

1998 to 2001 because of relatively low stock

ownership, they actually benefited from this (and the

relatively high share of houses in their portfolio)

in the 2001-2007 period. However, all three racial/ethnic

groups saw an increase in their debt to asset

ratio from 2001 to 2007.

The racial picture really changed radically by 2010. While

the ratio of both mean and median

income between black and white households changed very

little between 2007 and 2010 (mean

income, in particular, declined for both groups), the ratio

of mean net worth dropped from 0.19 to 0.14.

The proximate causes were the higher leverage of black

households and their higher share of housing

wealth in gross assets (see Table 10). In 2007, the

debt-equity ratio among blacks was an astounding

0.55, compared to 0.15 among whites, while housing as a

share of gross assets was 0.54 for the former

as against 0.31 for the latter. The ratio of mortgage debt

to home value was also much higher for

blacks, 0.49, than for whites, 0.32. The sharp drop in home

prices from 2007 to 2010 thus led to a

relatively steeper loss in home equity for the former, 25

percent, than the latter, 21 percent, and this

factor, in turn, led to a much steeper fall in mean net

worth for black households than white

households.26 Indeed, in terms of rates of return, while the

overall annual rate of return on net worth

among white households plummeted from 4.1% in 2001-2007 to

-7.7% in 2007-2010, it collapsed

from 6.4% to -10.9% among black households. It is of note

that black households had a much higher

return on net worth than white households in the 2001-2007

period but a much lower return in 2007-

2010.

The Great Recession actually hit Hispanic households much

harder than blacks in terms of

wealth. Mean income among Hispanic households rose a bit

from 2007 to 2010 and the ratio with

respect to white households increased from 0.50 to 0.57. On

the other hand, the median income of

Hispanics fell, as did the ratio of median income between

Hispanics and whites. However, the mean

net worth in 2010 dollars of Hispanics fell almost in half,

and the ratio of this to the mean wealth of

whites plummeted from 0.26 to 0.15. The same factors were

responsible as in the case of black

households. In 2007, the debt-equity ratio for Hispanics was

0.51, compared to 0.15 among whites,

while housing as a share of gross assets was 0.53 for the

former as against 0.31 for the latter (see Table

10). The ratio of mortgage debt to home value was also

higher for Hispanics, 0.45, than for whites,

0.32. As a result, net home equity dropped by 48 percent

among Hispanic home owners, compared to

21 percent among white home owners, and this factor, in

turn, was largely responsible for the huge

decline in Hispanic net worth both in absolute and relative

terms. In terms of the annual return on net

worth, it nosedived from 6.7% in 2001-2007 to -11.8% in

2007-2010. The drop was even steeper than

that for black households. In fact, while Hispanic

households had a higher return than white or black

households in 2001-2007, it had the lowest return in

2007-2010.

There are two reasons that might explain the extreme drop in

Hispanic net worth. First, a large

proportion of Hispanic home owners bought their home in the

interval from 2001 to 2007, when home

prices were peaking. This is reflected in the sharp increase

in their home ownership rate over this

period. As a result, they suffered a disproportionately

large percentage drop in their home equity.

Second, it is likely that Hispanic home owners were more

heavily concentrated than whites in parts of

the country like Arizona, California, Arizona, and Nevada

(the “sand states”) and Florida, where home

prices plummeted the most.

There was also a steep drop in the home ownership rate among

Hispanic households of 1.9

percentage points from 2007 to 2010. Indeed, after catching

up on white households in this dimension

from 1983 to 2007, Hispanic households fell back in 2010 to

the same level as in 2004.

9. Wealth shifts from the young to the old

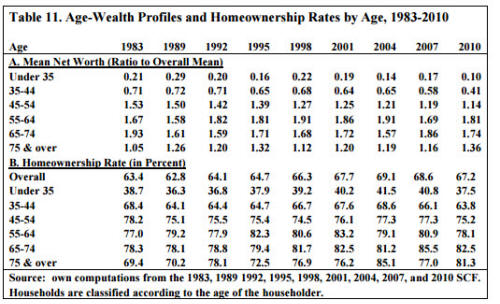

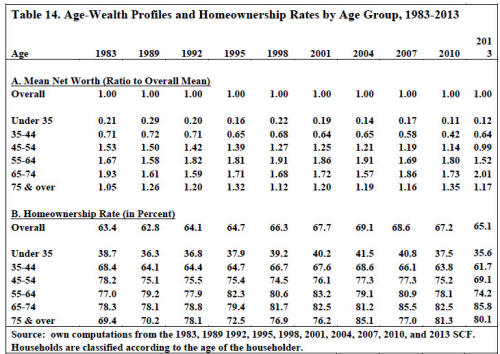

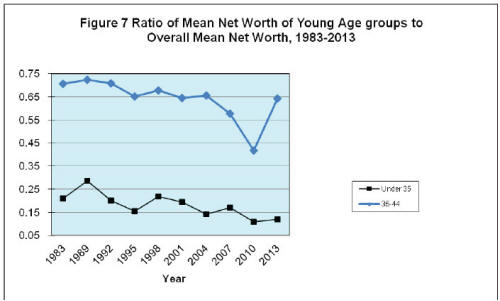

As shown in Table 11, the cross-sectional age-wealth

profiles generally follow the predicted

hump-shaped pattern of the life-cycle model. Mean wealth

increases with age up through age 65 or so

and then falls off. Home ownership rates have a similar

profile, though the fall-off after the peak age is

much more attenuated than for the wealth numbers (and in

2004 they actually show a steady rise with

age). In 2010, the wealth of elderly households (age 65 and

over) was 2.1 times as high as that of the

non-elderly and their homeownership rate was 19 percentage

points higher. Despite the apparent

similarity in the profiles, there were notable shifts in the

relative wealth holdings by age group from

1983 to 2007. The relative wealth of the youngest age group,

under 35 years of age, declined from 21

percent of the overall mean in 1983 to 17 percent in 2007.

In 2007, the mean wealth of the youngest

age group was $95,900 (in 2010 dollars), which was only

slightly more than the mean wealth of this

age group in 1989 ($93,100). Though as noted in Section 1,

educational loans expanded markedly over

the 2000s and by 2007 one third of households in this age

group reported a student loan outstanding,

still 74 percent of the total debt of this age group was

mortgage debt and only 9.5 percent took the

form of student loans.

The mean net worth of the next youngest age group, 35-44,

relative to the overall mean,

collapsed from 0.71 in 1983 to 0.58 in 2007. The relative

wealth of the next youngest age group, 45-

54, also declined, from 1.53 in 1983 to 1.19 in 2007. The

relative wealth of age group 55-64 was about

the same in 2007, 1.69, as in 1983,1.67. The relative net

worth of age group 65-74 plummeted from

1.93 in 1983 to 1.61 in 1989 but recovered to 1.86 in 2007.

The wealth of the oldest age group, age 75

and over, gained ground, from only 5 percent above the mean

in 1983 to 16 percent in 2007.

Changes in homeownership rates tend to mirror these trends.

While the overall ownership rate

increased by 5.2 percentage points from 63.4 to 68.6 percent

between 1983 and 2007, the share of

households in the youngest age group owning their own home

increased by only 2.1 percentage points.

The homeownership rate of households between 35 and 44 of

age actually fell by 2.3 percentage

points, and that of age group 45 to 54 years of age declined

by 0.9 percentage points. Big gains in

homeownership were recorded by the older age groups: 3.9

percentage points for age group 55-64, 7.1

percentage points for age group 65-74, and 7.6 percentage

points for the oldest age group.27 By 2007,

homeownership rates rose monotonically with age up to age

group 65-74 and then dropped for the

oldest age group. The statistics point to a relative

shifting of home ownership away from younger

towards older households between 1983 and 2007.

Changes in relative wealth were even more dramatic from 2007

to 2010. The relative wealth of

the under 35 age group plummeted from 0.17 to 0.10 and that

of age group 35-44 from 0.58 to 0.41,

while that of age group 45-54 fell somewhat from 1.19 to

1.14. In actual (2010) dollar terms, the

average wealth of the youngest age group collapsed from

$95,500 in 2007 to $48,400 in 2010, is

second lowest point over the 27 year period (the lowest

occurred in 1995),28 while the relative wealth

of age group 35-44 shrank from $325,00 to $190,000 its

lowest point over the whole 1983 to 2010

period. One possible reason for these steep declines in

wealth is that younger households were more

likely to have bought homes near the peak of the housing

cycle.

In contrast, the relative net worth of age group 55-64

increased sharply from 1.69 to 1.81

(though it shrank in actual 2010 dollar terms from $950,400

to $841,000) and that of the oldest age

group from 1.16 to 1.36 (though once again it was down in

absolute terms from $653,700 to

$629,100), though the relative wealth of age group 65 to 74

declined from 1.86 to 1.74 (and fell in

absolute dollars as well, from $1,048,600 to $808,500). Home

ownership rates fell for all age groups

from 2007 to 2010 (except the very oldest) but the

percentage point decline (3.3 percentage points)

was greatest for the youngest age group.

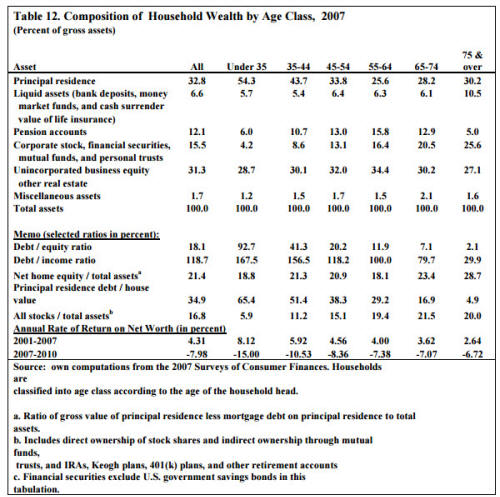

Changes in the relative wealth position of different age

groups depend in large measure on

relative asset price movements and differences in asset

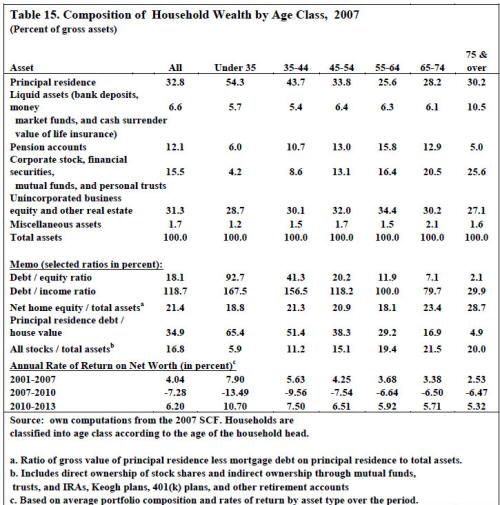

composition. The latter are highlighted in Table

12 for the year 2007. Homes comprised over half the value of

total assets for age group 35 and under,

and the share fell off with age to about a quarter for age

group 55-64 and then rose to 30 percent for

the oldest age group. Liquid assets as a share of total

assets remained relatively flat with age group at

around 6 percent except for the oldest group for whom it was

11 percent, perhaps reflecting the relative

financial conservativeness of older people. Pension accounts

as a share of total assets rose from 4

percent for the youngest group to 16 percent for age group

55 to 64 and then fell off to 5 percent for

the oldest age group. This pattern reflects the build-up of

retirement assets until retirement age and

then a decline as these retirement assets are liquidated.29

Corporate stock and financial securities

showed a steady rise with age, from a 4 percent share for

the youngest group to a 26 percent share for

the oldest. A similar pattern was evident for total stocks

as a percentage of all assets. Unincorporated

business equity and non-home real estate were relatively

flat as a share of total assets with age, about

30 percent. There was a pronounced fall off of the