|

Bulletin

Board Pix

Blame Mass

Incarceration

Time Served: The High

Cost, Low Return of Longer Prison Terms

by The PEW CENTER ON

THE STATES

Public Safety

Performance Project

June 2012

©2012 The Pew

Charitable Trusts.

The Pew Center on the

States is a division of The Pew Charitable Trusts that

identifies and

advances effective solutions to critical issues facing

states. Pew is a nonprofit organization

that applies a rigorous, analytical approach to improve

public policy, inform the public,

and stimulate civic life.

PEW CENTER ON THE

STATES

Susan K. Urahn,

managing director

Michael Caudell-Feagan,

deputy director

Research and Writing

Adam Gelb

Ryan King

Felicity Rose

Communications

Stephanie Bosh

Jennifer Laudano

Gita Ram

Gaye Williams

Design and Web

Jennifer Peltak

Evan Potler

Carla Uriona

EXTERNAL PROJECT TEAM

Avinash Bhati, Maxarth,

LLC (researcher)

Jenifer Warren

(writer)

EXTERNAL RESEARCH

SUPPORT

The following experts

provided valuable guidance in developing the research design

and

methodology featured in this report. Organizations are

listed for affiliation purposes only.

James F. Austin, JFA

Institute

Gerald G. Gaes,

Florida State University

Brian Ostrom, National

Center for State Courts

Stephen Raphael,

University of California-Berkeley (peer reviewer)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Valuable research

support was provided by the following Pew staff members:

Sachini Bandara,

Peter Gehred, Sean Greene, Sarika Gupta, Samantha Harvell,

Emily Lando, Aleena Oberthur,

and Denise Wilson. We would also like to thank William J.

Sabol and Ann Carson of the U.S.

Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics for

their invaluable guidance in the use of data

from the National Corrections Reporting Program, as well as

thinking through the intricacies

of estimating time served. George Camp and the staff of the

Association of State Correctional

Administrators assisted with coordination with departments

of corrections leadership.

For additional

information, visit

www.pewstates.org.

This report is

intended for educational and informational purposes.

References to specific policy makers

or companies have been included solely to advance these

purposes and do not constitute an endorsement,

sponsorship, or recommendation by The Pew Charitable Trusts.

©2012 The Pew

Charitable Trusts. All Rights Reserved.

901 E Street NW, 10th

Floor

Washington, DC 20004

2005 Market Street,

Suite 1700

Philadelphia, PA 19103

Contents

-

Executive Summary

-

Introduction

-

Length of Stay in

States

-

Unpacking the

Numbers: What Shapes Length of Stay?

-

What Do We Gain

from Increased Time Served?

-

How States Are

Modifying Length of Stay

-

Appendix A:

Estimating Length of Stay by State

-

Appendix B: Full

Methodology Criminal History Accumulation Process (CHAP)

-

Endnotes

Executive Summary

Over the past four

decades, criminal

justice policy in the United States was

guided largely by a central premise: the

best way to protect the public was to put

more people in prison. A corollary was

that offenders should spend longer and

longer time behind bars.

The logic of the

strategy seemed

inescapable—more inmates serving more

time surely equals less crime—and policy

makers were stunningly effective at putting

the approach into action. As the Pew

Center on the States has documented, the

state prison population spiked more than

700 percent between 1972 and 2011,

and in 2008 the combined federal-state-local

inmate count reached 2.3 million, or

one in 100 adults. Annual state spending

on corrections now tops $51 billion and

prisons account for the vast majority of the

cost, even though offenders on parole and

probation dramatically outnumber those

behind bars.

Indeed, prison

expansion has delivered

some public safety payoff. Serious crime

has been declining for the past two

decades, and imprisonment deserves some

of the credit. Experts differ on precise

figures, but they generally conclude

that the increased use of incarceration

accounted for one-quarter to one-third of

the crime drop in the 1990s. Beyond the

crime control benefit, most Americans

support long prison terms for serious,

chronic, and violent offenders as a means

of exacting retribution for reprehensible

behavior.

But criminologists and

policy makers

increasingly agree that we have reached

a “tipping point” with incarceration,

where additional imprisonment will have

little if any effect on crime. Research also

has identified new offender supervision

strategies and technologies that can help

break the cycle of recidivism.

Across the nation,

these developments,

combined with tight state budgets, have

prompted a significant shift toward

alternatives to prison for lower-level

offenders. Policy makers in several states

have worked across party lines to reform

sentencing and release laws, including

reducing prison time served by nonviolent

offenders. The analysis in this

study shows that longer prison terms have

been a key driver of prison populations

and costs, and the study highlights new

opportunities for state leaders to generate

greater public safety with fewer taxpayer

dollars.

A State-Level Portrait

of

Time Served

Prison populations

rise and fall according

to two principal forces: 1) how many

offenders are admitted to prison, and 2)

how long those offenders remain behind

bars. In this report, Pew seeks to help

policy makers better understand the

second factor—time served in prison.

Historically,

published statistics on

offenders’ length of stay in prison

consisted only of national estimates by

the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau

of Justice Statistics. The goal of this

Pew report is to go beyond the national

numbers and present a state-level portrait

of how time served has changed during

the past 20 years, how it has impacted

prison populations and costs, and how

policy makers can adjust it to generate

a better public safety return on taxpayer

dollars.

Toward that end, the

study identifies

trends in time served by state and by

type of crime from 1990 to 2009, using

National Corrections Reporting Program

data collected from 35 states by the U.S.

Census Bureau and the Bureau of Justice

Statistics. States not included in the study

had not reported sufficient data over the

1990–2009 study period. Pew also worked

with external researchers to analyze data

from three states to assess the relationship

between time served and public safety.

A Longer Stay in

Prison

According to Pew’s

analysis of state data

reported to the federal government,

offenders released in 2009 served an

average of almost three years in custody,

nine months or 36 percent longer than

offenders released in 1990. The cost

of that extra nine months totals an

average of $23,300 per offender. When

multiplied by the hundreds of thousands

of inmates released each year, the

financial impact of longer length of stay

is considerable. For offenders released

from their original commitment in 2009

alone, the additional time behind bars

cost states over $10 billion, with more

than half of this cost attributable to nonviolent

offenders.

“ We must change the

way in

which our laws work,

change the way in which the

system works, so that we can make

a clear distinction between those

who need to stay in prison to keep

the public safe versus those who

present little risk.”

—Hawaii Governor Neil

Abercrombie (D),

January 23, 2012

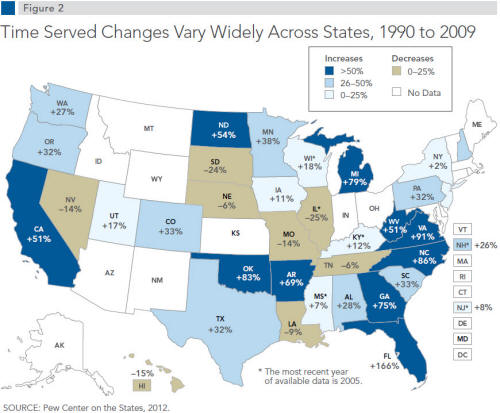

Although nearly every

state increased

length of stay during the past two decades,

the overall change varied widely among

states. In a few states, time served grew

rapidly between 1990 and 2009, among

them Florida (166 percent), Virginia (91

percent), North Carolina (86 percent),

Oklahoma (83 percent), Michigan (79

percent), and Georgia (75 percent). Eight

states reduced time served, including

Illinois (down 25 percent) and South

Dakota (down 24 percent). Among

prisoners released from reporting states in

2009, Michigan had the longest average

time served, at 4.3 years, followed closely

by Pennsylvania (3.8 years). South Dakota

had the lowest average time served at 1.3

years, followed by Tennessee (1.9 years).

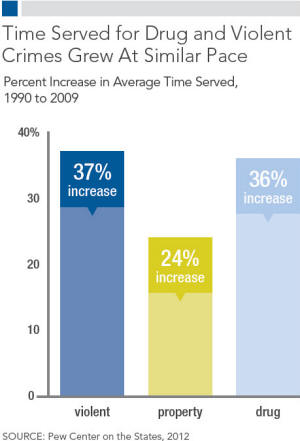

The growth in time

served was remarkably

similar across crime types. Offenders

released in 2009 served:

• For drug crimes: 2.2

years, up

from 1.6 years in 1990 (a 36 percent

increase)

• For property crimes:

2.3 years up

from 1.8 years in 1990 (a 24 percent

increase)

• For violent crimes:

5.0 years up

from 3.7 years in 1990 (a 37 percent

increase)

Again, the national

numbers mask large

interstate variation. For violent crimes,

Florida led the way among states with

a 137 percent increase in length of stay,

while prison stays for New York’s violent

inmates rose only 24 percent. Property

offenders in nine of 35 states served

less time on average in the last available

year of data compared with 1990, even

as those in Georgia, Florida, Virginia,

Oklahoma, and West Virginia saw average

increases of more than a year. States such

as Arkansas, Florida, and Oklahoma more

than doubled average time served by drug

offenders, even as Illinois, Missouri, New

York, Tennessee, and Nevada cut average

time served for the same group.

Time Served for Drug

and Violent

Crimes Grew At Similar Pace

Percent Increase in

Average Time Served,

1990 to 2009

SOURCE: Pew Center on

the States, 2012

A Questionable Impact

on

Public Safety

Despite the strong

pattern of increasing

length of stay, the relationship between

time served in prison and public safety

has proven to be complicated. For a

substantial number of offenders, there is

little or no evidence that keeping them

locked up longer prevents additional

crime.

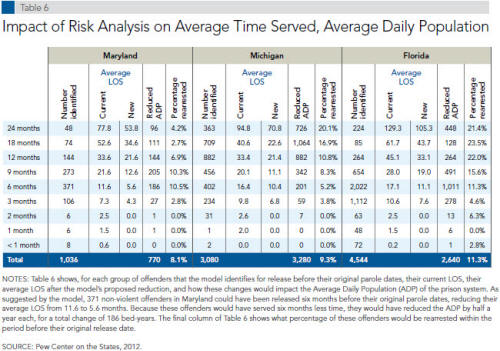

A new Pew analysis

conducted by external

researchers using data from three states—

Florida, Maryland, and Michigan—found

that a significant proportion of nonviolent

offenders who were released in

2004 could have served shorter prison

terms without impacting public safety.

The analysis identifies how much sooner

offenders could have been released,

based on a risk assessment that considers

multiple factors including criminal history,

the amount of time each person has

already served in prison, and other data.

Looking only at non-violent offenders,

the analysis identified 14 percent of the

offenders in the Florida release cohort, 18

percent of the offenders in the Maryland

release cohort, and 24 percent of the

Michigan release cohort who could have

served prison terms shorter by between

three months and two years without

jeopardizing public safety.

Using this type of

empirical analysis to

inform release policies could reduce

state prison populations and costs. If the

reductions in length of stay identified by

the risk analysis had been applied to nonviolent

offenders in Florida, Maryland,

and Michigan in 2004, the average daily

prison population in those states would

have been reduced by as much as 2,600

(3 percent), 800 (5 percent), and 3,300

(6 percent) respectively. These reductions

represent substantial cost savings in each

state: $54 million in Florida, $30 million

in Maryland, and $92 million in Michigan.

“ As we reserve more

of our

expensive [prison] bed space

for truly dangerous criminals [we]

free up revenue to deal with those

who are not necessarily dangerous

but are in many ways in trouble

because of various addictions.”

—Georgia Governor

Nathan Deal (R), May 1, 2012

States Begin to

Moderate

Time Served

Policy makers in all

three branches of

government can pull a variety of levers to

adjust the amount of time offenders serve

in prison. Prison time is influenced by

both front-end (sentencing) and back-end

(release) policy decisions. In several states,

policy makers have undertaken reforms

intended to stem the growth in time served,

or actually reverse it, for certain offense

types. These initiatives include:

• Raising the

threshold dollar amount

required to trigger certain felony

property crime classifications. States

include Alabama, Arkansas, California,

Delaware, Montana, South Carolina,

and Washington.

• Revising drug

offense classification

in the criminal code to ensure the

most serious offenders receive the

most severe penalties. States include

Arkansas, Colorado, and Kentucky.

• Rolling back

mandatory minimum

sentencing provisions. States include

Delaware, Indiana, Michigan,

Minnesota, and New York.

• Increasing

opportunities to earn

reductions in time served by completing

prison-based programs. States include

Colorado, Kansas, Pennsylvania, and

Wisconsin.

• Revising eligibility

standards for parole

consideration. States include Mississippi

and South Carolina.

Strong Public Support

for

Reform

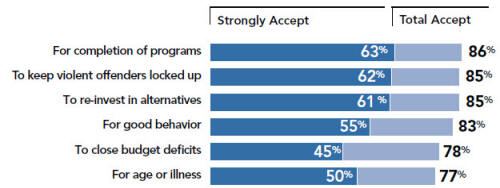

Recent opinion polling

suggests that these

reforms are being received well by the public.

A national January 2012 poll of 1,200 likely

voters revealed that the public is broadly

supportive of reductions in time served for

non-violent offenders as long as the twin

goals of holding offenders accountable and

protecting public safety still can be achieved.

Voters overwhelmingly prioritize preventing

recidivism over requiring non-violent

offenders to serve longer prison terms.

Nearly 90 percent support shortening prison

terms by up to a year for low-risk, nonviolent

offenders if they have behaved well

in prison or completed programming, and

voters also support reinvesting prison savings

into alternatives to incarceration.

* * * * *

The past five years

have seen significant

shifts in corrections policy across the

nation, prompted both by tight budgets

and by increasing understanding that there

are more effective, less expensive ways to

handle non-violent offenders than lengthy

spells of incarceration. Public opinion, long

concerned with controlling crime, is now

focused more on cost-effectiveness and

recidivism reduction than on traditional

measures of “toughness.”

Today, policy makers

have a much better

idea of what works to increase public safety

than they did in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Research clearly shows there is little return

on public dollars for locking up low-risk

offenders for increasingly long periods of

time and, in the case of certain non-violent

offenders, there is little return on locking

them up at all. In addition, actors at both

sentencing and release stages of the system

have increasingly sophisticated tools to help

them identify these lower-risk offenders.

States have been using

this new

information to improve results and

reduce costs, and the analysis in this

report shows that more savings can be

garnered by thoughtfully calibrating

time served, and thus ensuring there

is adequate prison space for the most

serious offenders. These promising

practices and many others can serve as

models for states looking to conserve

precious public dollars while keeping

communities safe.

Introduction

Between 1991 and 1995

the number of

media reports on crime in the United

States more than tripled, coinciding with

a jump in public concern about the issue.1

Federal and state lawmakers saw the

reports and responded quickly. Reasoning

that harsher sentences enacted in the

1970s and 1980s had been responsible

for the declining crime rates of the early

1990s, they decided the answer was to go

still further. At the time, little attention was

paid to the impacts extending prison terms

might have on public safety, or on costs to

taxpayers.

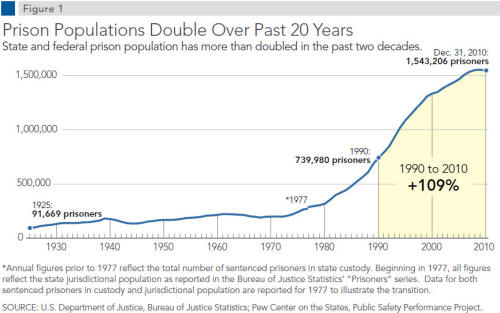

The consequences are

now well known.

By 2008, the American prison population

had soared—one out of every 100 adults

was behind bars (see Figure 1). With this

growth in prison population has brought

rising costs. Across states, investment in

corrections has jumped more than 300

percent in the past two decades, with

expenditures now totaling more than $51

billion annually, or 7.3 percent of all state

general fund spending.2

Greater imprisonment

clearly has yielded

public safety dividends, accounting for

an estimated one-quarter to one-third of

the crime drop during the 1990s.3 And

in some cases, longer sentences were not

only warranted to serve justice but also

necessary to protect the public.

Although few Americans

would question

the wisdom of tough sentences for violent,

chronic offenders, most criminologists

now consider the increased use of prison

for non-violent offenders a questionable

public expenditure, producing little

additional crime control benefit for each

dollar spent.4 During the past decade,

all 17 states that cut their imprisonment

rates also experienced a decline in crime

rates.5 And a 2006 legislative analysis

in Washington State found that while

incarcerating violent offenders provides a

net public benefit by saving the state more

than it costs, imprisonment of property

and drug offenders leads to negative

returns.6

Figure 1. Prison

Populations Double Over Past 20 Years: State and federal

prison population has more than doubled in the past two

decades.

*Annual figures prior to 1977 reflect the total number of

sentenced prisoners in state custody. Beginning in 1977, all

figures

reflect the state jurisdictional population as reported in

the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ “Prisoners” series. Data

for both

sentenced prisoners in custody and jurisdictional population

are reported for 1977 to illustrate the transition.

SOURCE: U.S.

Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Pew

Center on the States, Public Safety Performance Project.

Policy makers, anxious

to conserve

taxpayer dollars without sacrificing public

safety, are now rethinking the “longer is

better” approach to punishment. In the

past five years more than a dozen states,

starting with Texas and Kansas in 2007,

have enacted comprehensive sentencing

and corrections reforms, typically shifting

non-violent offenders from prison and

using the savings to fund more effective,

less expensive alternatives. Partly due

to these and other policy changes, 2009

was the first year in nearly four decades

during which the state prison population

declined.7

A New Focus on Time

Served

The prison population

is driven by two

factors: first, how many offenders are

admitted to prison, and second, how

long they stay. This report focuses on

the second mechanism—time served,

or length of stay (LOS), in prison.

Understanding the length of time offenders

are being held in prison, and how and why

the time period has changed over time,

is a critical first step toward helping state

leaders factor LOS into their assessments

of state crime and punishment policies.

Earlier research

identified national trends

in how long offenders stay in prison, but

little is known about how LOS varies

at the state level. The U.S. Department

of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics

publishes an annual estimate of average

LOS nationally, but there is no such

resource for state numbers. A search of

state Departments of Corrections websites

revealed that fewer than half of the states

publish publicly available numbers on

LOS, with only five states providing such

data going back more than 10 years. And

each state uses its own definitions and

measures, which hampers comparability.

Thus the first section of this report

presents state-level estimates of how much

time offenders spend in prison and how

this has changed since 1990.

Beyond that snapshot,

it is also essential

to understand how and why LOS varies

among states. Time served is influenced

by both front-end (sentencing) and backend

(release) policy decisions—and to

a lesser extent by policies and practices

within prisons. Since the 1980s, states

have adopted a wide variety of both frontend

and back-end changes that have

lengthened LOS for the average offender.

In the second section

of this report, we

explore the factors that affect time served.

We offer case studies of three states—

California, Florida, and Pennsylvania—to

demonstrate the complexity of the issues

and the need for policy makers to look

beyond the big picture trends to uncover

the specific factors at play in their states.

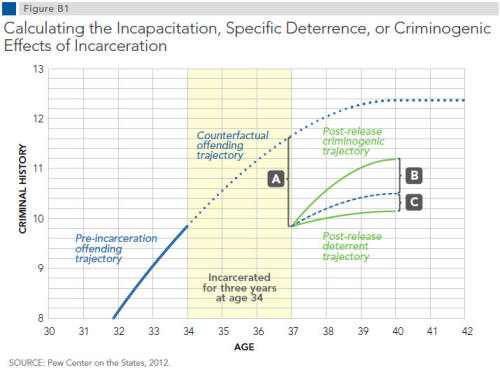

We conclude the report

by exploring how

time served relates to public safety. We

present new research on whether current

levels of time served are promoting safe

communities in the most cost-effective

way. It is important to note that higher

cost is not necessarily a concern in

itself. Longer prison terms may well be

justified if policy makers believe that prior

punishments simply were inadequate

to reflect society’s need for retribution

for the crime. But penalties typically are

enhanced with public safety in mind, and

an expectation that longer prison terms

will reduce the total number of crimes that

offenders will commit. When these are the

goals, cost takes center stage and the key

question becomes not whether increasing

time served will reduce crime but rather,

“What is the best way to achieve the

greatest reduction in crime.”

Length of Stay in

States

Using National

Corrections Reporting

Program (NCRP) data collected by the

U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau

of Justice Statistics, Pew estimated

the average length of stay (LOS) for

offenders released in each year from

1990 to 2009 (see Figure 2).

The NCRP gathers data

from states on

a voluntary basis. Thirty-five states,

representing 89 percent of 2009 prison

releases, submitted data in a sufficient

number of years to allow estimates to be

calculated. Details on the methodology

are in the Appendix A.

Figure 2. Time Served

Changes Vary Widely Across States, 1990 to 2009

* The most recent year

of available data is 2005.

SOURCE: Pew Center on

the States, 2012.

Defining Length of

Stay

Length of stay can be

measured in

several ways. The most common is the

“release cohort” measure, which we

call the “average LOS,” and that is the

primary measure we use in this report.

Considerations involved in measuring

LOS include:

Average vs. Expected

LOS: “Average

LOS” measures the average time spent

in custody for offenders released in a

certain time period, usually one calendar

year. A second measure we call “expected

LOS” looks at the inmates in prison

during a given year and estimates how

long those inmates are likely to spend in

custody based on what percentage of the

population exits prison in that year. The

expected LOS will differ from the average

LOS if sentencing and release policies

are changing and inmates admitted more

recently will be serving shorter or longer

terms than their predecessors.

All Releases vs. First

Releases: Prison

populations in many states include both

offenders serving time on their original

offenses and offenders who served time,

were released, and were returned to

prison for a violation of their parole or

other supervised release. Because parole

violators may serve shorter periods and

it is more difficult to compare these

groups accurately across states, we focus

solely on “first releases”—that is, people

released from their original sentence for

the first time.

Figure 3. Time Is

Money

Cost of longer time

served tops $10 billion

for offenders released in 2009.

*First releases only.

SOURCE: Pew Center on

the States, 2012.

$2,593: Average

cost of one month

in prison, FY 2010

9 months:

Additional time offenders released

in 2009 served relative to 1990

$23,333: Average

cost of keeping

offenders in prison longer

*445,688:

Offenders released in 2009 (50 states)

$10.4 billion:

Total state cost of

keeping offenders

released in 2009 in

prison longer

Prison Time vs. Total

Custody Time:

Most prison inmates

have spent some

period of time in jail before being

convicted and transferred to state prison.

Because this jail time counts toward an

offender’s sentence, we also count it as part

of an offender’s total LOS. When data on

an individual’s jail time were unavailable,

we estimated it based on the year and

offense category.

All Offenders

Pew estimates that the

average LOS for

offenders released from prison in reporting

states rose by 36 percent between 1990

and 2009 (see Table 1).8 Offenders

released in 2009 spent an average of 2.9

years in custody, nine months longer

than those released in 1990. While nine

months per inmate may not sound like a

long time, even a relatively small difference

in average time served can make a large

difference for an overall population. For

instance, considering only those offenders

released in 2009, an average increase of

nine months translates to cost increases of

more than $10 billion (see Figure 3).9 This

impact is magnified by successive cohorts

of offenders serving longer periods; each

cohort stacks on top of the cohort before,

leading to greater overall growth in the

prison population.

Among prisoners

released in 2009 from

reporting states, Michigan had the longest

average time served, at 4.3 years, followed

closely by Pennsylvania (3.8 years), New

York (3.6 years), and Virginia (3.3 years).

South Dakota had the lowest average time

served at 1.3 years, followed by Tennessee

(1.9 years), and Missouri (2.1 years), and

North Dakota (2.0 years).

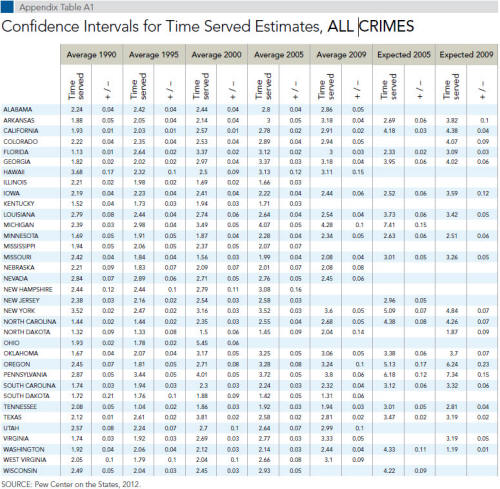

Table 1. Avg. Time

Served Estimates

ALL CRIMES

State / 1990 / 2009 / Percentage change

ALABAMA / 2.2 /

2.9 / 28%

ARKANSAS / 1.9 /

3.2 / 69%

CALIFORNIA / 1.9 /

2.9 / 51%

COLORADO / 2.2 /

2.9 / 33%

FLORIDA / 1.1 /

3.0 / 166%

GEORGIA / 1.8 /

3.2 / 75%

HAWAII / 3.7 / 3.1

/ –15%

ILLINOIS / 2.2 /

1.7* / –25%

IOWA / 2.2 / 2.4 /

11%

KENTUCKY / 1.5 /

1.7* / 12%

LOUISIANA / 2.8 /

2.5 / –9%

MICHIGAN / 2.4 /

4.3 / 79%

MINNESOTA /

1.7 2.3 / 38%

MISSISSIPPI / 1.9

/ 2.1* / 7%

MISSOURI / 2.4 /

2.1 / –14%

NEBRASKA / 2.2 /

2.1 / –6%

NEVADA / 2.8 / 2.5

/ –14%

NEW HAMPSHIRE

/ 2.4 / 3.1* / 26%

NEW JERSEY / 2.4 /

2.6* 8%

NEW YORK / 3.5 /

3.6 / 2%

N. CAROLINA / 1.4

/ 2.7 / 86%

N. DAKOTA / 1.3 /

2.0 / 54%

OKLAHOMA / 1.7 /

3.1 / 83%

OREGON / 2.4 / 3.2

/ 32%

PENNSYLVANIA / 2.9

/ 3.8 / 32%

S. CAROLINA / 1.7

/ 2.3 / 33%

S. DAKOTA / 1.7 /

1.3 / –24%

TENNESSEE / 2.1 /

1.9 / –6%

TEXAS / 2.1

2.8 / 32%

UTAH / 2.6 / 3.0 /

17%

VIRGINIA / 1.7 /

3.3 / 91%

WASHINGTON / 1.9 /

2.4 / 27%

WEST VIRGINIA /

2.1 / 3.1 / 51%

WISCONSIN / 2.5 /

2.9* / 18%

NATIONAL / 2.1

2.9 / 36%

* The most recent

year of available data is 2005.

NOTES: Time Served

estimates are in years. Ohio is omitted

due to irregularities with 2002 data.

SOURCE: Pew Center on the States, 2012.

* Includes some

offenses that are not counted in violent, property, or drug

categories.

SOURCE: Pew Center on the States, 2012.

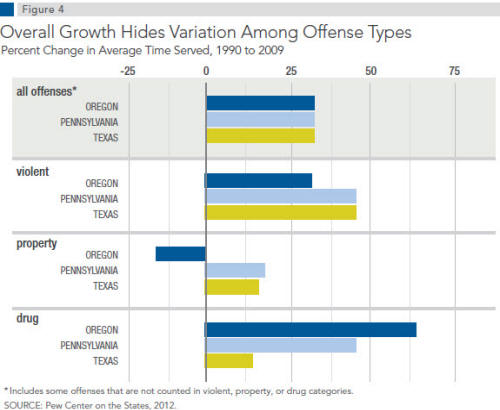

Figure 4. Overall Growth Hides Variation Among Offense Types

Percent Change in

Average Time Served, 1990 to 2009

* Includes some

offenses that are not counted in violent, property, or drug

categories.

SOURCE: Pew Center on

the States, 2012.

The overall change in

LOS during the

period from 1990 to 2009 varied widely

among states (see Table 1). A few states

saw very large increases, among them

Florida (166 percent), Virginia (91 percent),

North Carolina (86 percent), Oklahoma

(83 percent), Michigan (79 percent), and

Georgia (75 percent).10 Time served actually

dropped in eight states, including Illinois

(down 25 percent), South Dakota (down 24

percent), Hawaii (down 15 percent), and

Missouri and Nevada (down 14 percent).

Nationally, the

fastest period of growth

in time served came between 1995 and

2000. In that period, LOS rose 28 percent,

compared with less than 5 percent in

the five-year periods before and after.

Most states mirrored this pattern, with

rapid growth in the late 1990s followed

by moderate growth or leveling off. The

most variation between states occurred

in the early 2000s, after some states had

experienced rapid growth. The differences

narrowed in the past five years, as the

others caught up.

Defining Violent

Offenses

Defining Violent

Offenses

For the purposes of

classification across

states, the broad offense definitions used

in this study are based on the most serious

offense for which an individual is currently

serving time. Crimes in some of the violent

offenses category include but are not

limited to:

• aggravated assault

• armed robbery

• child endangerment

• child molestation

• domestic violence

• extortion

• homicide

• kidnapping

• manslaughter

• rape

• reckless

endangerment

• robbery

• simple assault

In order to explain

the interstate

variation in LOS, Pew classified offenders

into three offense categories—violent,

drug, and property—and created LOS

estimates for each of these categories

in each state and year (see examples

in Figure 4). Offenders not fitting into

these categories (such as offenders

convicted of quality of life and weapons

offenses) were included in the total

calculations but are not presented as a

separate category.

Violent Offenders

Violent offenders

released in 2009 served

an average of five years in custody, an

increase of 37 percent from 3.7 years

in 1990. Some simple math shows the

impact of that seemingly modest rise.

Multiplied by the number of first releases

of violent offenders in 2009, this cohort

cost $4.7 billion more than had they

served the 1990 average of 3.7 years in

prison. This figure is less than half of the

total cost of increased time served ($10

billion) between 1990 and 2009, with the

balance comprised of an increase in LOS

for non-violent offenders.

Time Served

Of all the violent

offenders released

in 2009, those in Michigan served the

longest average time in custody, 7.6 years,

followed by Hawaii at 6.2 years (see Table

2). Alabama, New York, and Virginia

were close behind, with released violent

offenders in those states serving an average

of 6.0 years. Offenders in South Dakota

had the shortest average length of stay

among the reporting states at 2.5 years,

followed by North Dakota (3.0 years),

Minnesota (3.2 years), and Nebraska (3.3

years).

It is important to

note that the violent

crime category includes a wide range of

offense types (see sidebar). The significant

variation in sentence length and time

served for the offenses comprising the

violent crime category means that state

averages will obscure important offense

variation to a greater degree than among

drug or property offenses. For example,

the national average of time served for

simple assault is 2.7 years, which is half

the average for all violent offenses. On

the other end of the offense severity

spectrum, the time served for released

offenders convicted of murder is nearly

triple the figure for all violent offenders.

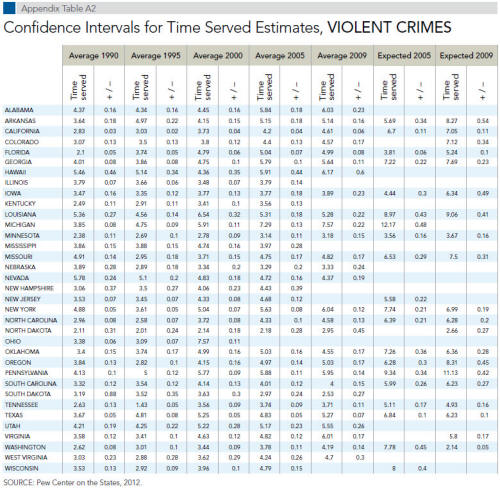

Table 2. Avg. Time

Served Estimates

VIOLENT CRIMES

Table 2. Avg. Time

Served Estimates

VIOLENT CRIMES

State / 1990 /

2009 / Percentage change

ALABAMA / 4.4 /

6.0 / 38%

ARKANSAS / 3.6 /

5.1 / 41%

CALIFORNIA / 2.8 /

4.6 / 63%

COLORADO / 3.1 /

4.6 / 49%

FLORIDA / 2.1 /

5.0 / 137%

GEORGIA / 4.0 /

5.6 / 41%

HAWAII / 5.5 / 6.2

/ 13%

ILLINOIS / 3.8 /

3.8* / 0%

IOWA / 3.5

3.9 / 12%

KENTUCKY / 2.5 /

3.6* / 43%

LOUISIANA / 5.4 /

5.3 / –2%

MICHIGAN /

3.9 /7.6 / 97%

MINNESOTA / 2.4 /

3.2 / 34%

MISSISSIPPI / 3.9

/ 4.0* / 3%

MISSOURI / 4.9 /

4.8 / –2%

NEBRASKA / 3.9 /

3.3 / –15%

NEVADA / 5.8

/ 4.4 / –24%

NEW HAMPSHIRE /

3.1 / 4.4* / 45%

NEW JERSEY / 3.5 /

4.7* / 33%

NEW YORK / 4.9 /

6.0 / 24%

N. CAROLINA / 3.0

/ 4.6 / 55%

N. DAKOTA / 2.1 /

3.0 / 40%

OKLAHOMA / 3.4 /

4.5 / 34%

OREGON / 3.8 / 5.0

/ 31%

PENNSYLVANIA / 4.1

/ 5.9 / 44%

S. CAROLINA / 3.3

/ 4.0 / 21%

S. DAKOTA / 3.2 /

2.5 / –21%

TENNESSEE / 2.6 /

3.7 / 41%

TEXAS / 3.7 / 5.3

/ 44%

UTAH / 4.2 / 5.5 /

32%

VIRGINIA / 3.6 /

6.0 / 68%

WASHINGTON / 2.6 /

4.2 / 60%

WEST VIRGINIA /

3.0 / 4.7 / 55%

WISCONSIN / 3.5 /

4.8* / 36%

NATIONAL / 3.7 /

5.0 / 37%

* The most recent

year of available data is 2005.

NOTES: Time Served

estimates are in years. Ohio is omitted

due to irregularities with 2002 data.

SOURCE: Pew Center

on the States, 2012.

It is important to

note that the method

of estimating average time served in this

report includes data only from released

offenders. Inmates still in prison and

serving long sentences, including life

terms, are not included in the calculation.

Thus, the average time served of released

offenders may understate the average time

served for all offenders in the system. This

is a critical consideration when assessing

time served for violent offenders, who

typically serve longer sentences. See the

sidebar on expected time served (pages

21–22) for more information on alternative

methods of calculating time served for

violent offenders.

Trends

Looking at how time

served by violent

offenders changed over time, Florida led

the way among states with a 137 percent

increase. Michigan followed with a 97

percent jump in LOS, while prison stays for

Virginia’s violent inmates rose 68 percent.

Overall, time served for violent offenders

rose steadily across the 20-year period,

though some states saw sharp increases in

the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Within the wide group

of prisoners

classified as violent offenders, trends over

time also vary greatly by specific offense.

While the national average LOS for all

violent offenses increased by 37 percent

between 1990 and 2009, the average for

convicted murderers nearly doubled. For

all offenses discussed in this report, it is

critical for policy makers to keep in mind

that the categories presented are aggregates

of many offense types and caution should be

used in drawing policy conclusions about any

specific sub-category without undertaking

further investigation.

Policy Changes

The main mechanism

states used to

increase time served for violent offenders

was to require that offenders serve a larger

percentage of their sentences. Violent inmates

released in 2009 from the reporting states

served almost 80 percent of their sentences,

up from about 50 percent in 1990.

In the early 1990s,

both time served

and percentage of sentence served were

flat. However in 1994, when the federal

government created an incentive for states

to implement “truth in sentencing” statutes

requiring violent offenders to serve a larger

proportion of their sentences, both percentage

of sentence served and time served began to

rise and continued to increase at about the

same rate for the next 15 years.

At the same time as

violent offenders were

serving a higher percentage of their sentences,

average sentences were declining, from 7.4

years in 1990 to 6.4 years in 2009, somewhat

offsetting the trend toward increasing time

served.

But this dynamic varied by state. In New

York, both sentencing and release policy

changes contributed to longer time served.

Violent offenders served 60 percent of their

sentences in 1990 and 68 percent in 2009,

a 13 percent increase, while sentences grew

from 8.1 years to 8.9 years, a 10 percent

increase. Overall, in four states LOS was

mainly driven by increases in sentence length,

as opposed to 18 states where LOS was

driven by increase in percentage of sentence

served, and five states where the two drivers

were roughly equal.11 Accompanying state fact

sheets, available online, explore state-specific

patterns in more detail.

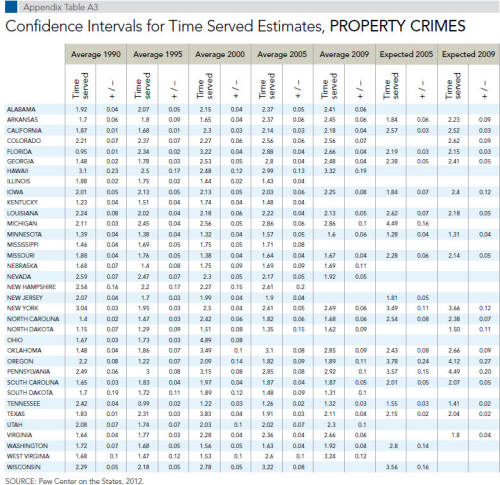

Property Offenders

Overall, length of

stay for offenders serving

time for property crimes grew from 1.8 years

on average in 1990 to 2.3 years in 2009,

costing an additional $1.8 billion.

Defining PROPERTY

Offenses

For the purposes of

classification across

states, the broad offense definitions used

in this study are based on the most serious

offense for which an individual is currently

serving time. Crimes in the property

offenses category include but are not

limited to:

• arson

• breaking and entering

• burglary

• embezzlement

• forgery

• fraud

• motor vehicle theft

• sale of stolen property

• shoplifting

• trespassing

Time Served

Property offenders

released in West

Virginia and Hawaii in 2009 served 3.2

and 3.3 years on average, a full year longer

than the national average (see Table 3).

South Dakota and Tennessee tied for

the shortest average LOS for property

offenders released in 2009, at 1.3 years in

each state, a full year less than the average.

Trends

The highest rate of

growth was in

Florida, where the increase in LOS was

181 percent; Oklahoma (93 percent)

and West Virginia (93 percent) also

had high increases in LOS. But more

than a quarter of states had an overall

decrease in LOS for property offenders,

including Tennessee (45 percent), South

Dakota (23 percent), and Oregon (14

percent). The wide variation among

states could reflect changing offense

compositions, in which more low-level

property offenders are imprisoned,

or a deliberate shifting of resources

within prisons to make more room for

violent offenders. Both possibilities are

discussed further below.

Table 3. Avg. Time Served Estimates

PROPERTY CRIMES

State / 1990 /

2009 / Percentage change

ALABAMA / 1.9 /

2.4 / 25%

ARKANSAS / 1.7 /

2.5 / 44%

CALIFORNIA / 1.9 /

2.2 16%

COLORADO / 2.2 /

2.6 / 16%

FLORIDA / .9 / 2.7

/ 181%

GEORGIA / 1.5 /

2.5 / 68%

HAWAII / 3.1 / 3.3

/ 7%

ILLINOIS / 1.9 /

1.4* / –24%

IOWA / 2.0 / 2.3 /

12%

KENTUCKY / 1.2 /

1.5* / 20%

LOUISIANA / 2.2 /

2.1 / –5%

MICHIGAN / 2.1 /

2.9 / 35%

MINNESOTA / 1.4 /

1.6 / 16%

MISSISSIPPI / 1.5

/ 1.7* / 17%

MISSOURI / 1.9 /

1.7 / –11%

NEBRASKA / 1.7 /

1.7 / 0%

NEVADA / 2.6

/ 1.9 / –26%

NEW HAMPSHIRE /

2.5 / 2.6* / 3%

NEW JERSEY / 2.1 /

1.9* / –9%

NEW YORK / 3 / 2.7

/ –11%

N. CAROLINA / 1.4

/ 1.7 / 20%

N. DAKOTA / 1.1 /

1.6 / 41%

OKLAHOMA / 1.5 /

2.9 / 93%

OREGON / 2.2

/ 1.9 / –14%

PENNSYLVANIA / 2.5

/ 2.9 / 17%

S. CAROLINA

/ 1.6 / 1.9 / 13%

S. DAKOTA / 1.7 /

1.3 / –23%

TENNESSEE / 2.4 /

1.3 / –45%

TEXAS / 1.8 / 2.1

15%

UTAH / 2.1 /

2.3 / 10%

VIRGINIA / 1.6 /

2.7 / 62%

WASHINGTON / 1.7 /

1.9 / 11%

WEST VIRGINIA /

1.7 / 3.2 / 93%

WISCONSIN / 2.3 /

3.2* / 40%

NATIONAL / 1.8 /

2.3 / 24%

* The most recent

year of available data is 2005.

NOTES: Time Served

estimates are in years. Ohio is omitted

due to irregularities with 2002 data.

SOURCE: Pew Center

on the States, 2012.

Policy Changes

Released property

offenders served an

average of 67 percent of their court-ordered

sentences in 2009, a significant

jump up from 43 percent in 1990. Average

sentences dropped from 4.3 years to 3.4

years, illustrating that time served was

driven by changes in release policy rather

than by increases in sentences.

These trends were not

uniform across

states; in 16 of the 32 states that reported

sentencing data, sentences rose, including

12 in which average sentences grew while

percentage of sentence served fell.

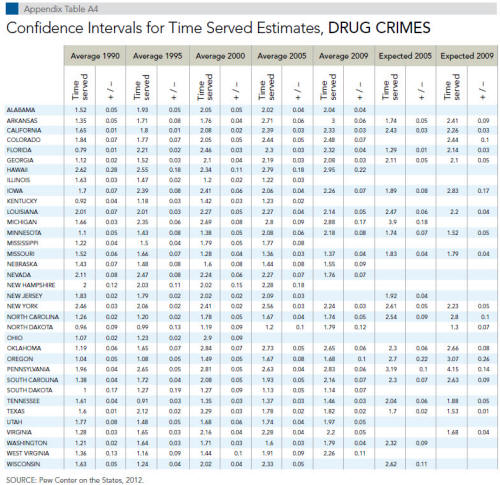

Drug Offenders

Drug offenders

released in 1990 served an

average of 1.6 years in custody, compared

with 2.2 years in 2009, an increase of 36

percent. At the same time, the number of

drug offenders sent to prison grew rapidly.

Without accounting for the change in

admissions, the 2009 cohort cost around

$2.3 billion due to the increased time

served. Considering the cumulative effects

of the change in LOS as well as the growth

in the number of drug offenders admitted

to and released from prison, the overall

impact of drug policy changes on prison

space used is significantly higher.

Time Served

Drug offenders

released in Arkansas (3.0

years), Hawaii (2.9 years), and Michigan

(2.9 years) in 2009 served the longest

average period in custody (see Table

4). Meanwhile drug offenders released

in South Dakota served an average of

1.1 years, the shortest term among the

reporting states.

Trends

Arkansas also had one

of the largest

increases since 1990, with LOS rising by

122 percent for drug offenders. Florida’s

drug offenders served nearly three times

as long in 2009 as in 1990—a 194

percent increase. Oklahoma also more

than doubled its average LOS with a 122

percent increase. Demonstrating a small

counter trend, five states saw time served

for drug crimes decrease during the past

two decades, with the largest decrease

in Illinois (a 25 percent decline between

1990 and 2005).

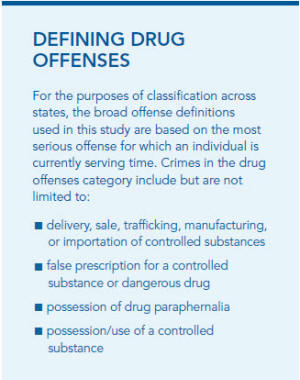

Defining DRUG

Offenses

For the purposes of

classification across

states, the broad offense definitions

used in this study are based on the most

serious offense for which an individual is

currently serving time. Crimes in the drug

offenses category include but are not

limited to:

• delivery, sale,

trafficking, manufacturing, or importation of controlled

substances

• false prescription

for a controlled substance or dangerous drug

• possession of drug

paraphernalia

• possession/use of a

controlled substance

The growth in LOS for

drug crimes took

place almost entirely in the 1990s, with 81

percent of states increasing LOS between

1990 and 2000. In the 2000s, 55 percent

of states experienced an increase in LOS,

while 45 percent saw LOS decrease

(although the average generally still

remained above 1990 levels).

Policy Changes

In 2009, released drug

offenders served

a larger percentage of their sentences

than in 1990 (61 percent as opposed

to 42 percent). Average sentences rose

from 1990 to 2001 and then began to

decline, leading to a small overall decline

in sentence length from 3.8 years in

1990 to 3.6 years by 2009. This national

decline was driven by Texas, Virginia, and

North Carolina, where sentences for drug

offenders decreased precipitously in the

early 2000s.

Table 4. Avg. Time Served Estimates

DRUG CRIMES

State / 1990 /

2009 / Percentage change

ALABAMA / 1.5 /

2.0 / 35%

ARKANSAS / 1.4 /

3.0 / 122%

CALIFORNIA / 1.6 /

2.3 / 41%

COLORADO / 1.8 /

2.5 / 35%

FLORIDA / 0.8 /

2.3 / 194%

GEORGIA / 1.1 /

2.1 / m85%

HAWAII / 2.6 / /

2.9 / 12%

ILLINOIS / 1.6 /

1.2* / –25%

IOWA / 1.7 / 2.3 /

33%

KENTUCKY / .9 /

1.2* 34%

LOUISIANA / 2.0 /

2.1 / 7%

MICHIGAN / 1.7

2.9 / 74%

MINNESOTA / 1.1 /

2.2 / 99%

MISSISSIPPI / 1.2

/ 1.8* / 45%

MISSOURI / 1.5 /

1.4 / –10%

NEBRASKA / 1.4 /

1.6 / 8%

NEVADA / 2.1 / 1.8

/ –16%

NEW HAMPSHIRE /

2.0 / 2.3* / 14%

NEW JERSEY / 1.8 /

2.1* / 14%

NEW YORK / 2.5 /

2.2 / –9%

N. CAROLINA / 1.3

/ 1.7 / 38%

N. DAKOTA / 1.0 /

1.8 / 86%

OKLAHOMA / 1.2

/ 2.6 / 122%

OREGON / 1.0 / 1.7

/ 62%

PENNSYLVANIA / 2.0

/ 2.8 / 44%

S. CAROLINA / 1.4

/ 2.2 / 57%

S. DAKOTA /

1.0 / 1.1 / 15%

TENNESSEE / 1.6 /

1.5 / –9%

TEXAS / 1.6 / 1.8

/ 14%

UTAH / 1.8 / 2.0 /

11%

VIRGINIA / 1.3 /

2.2 / 72%

WASHINGTON / 1.2 /

1.8 / 48%

WEST VIRGINIA /

1.4 / 2.3 / 66%

WISCONSIN / 1.6 /

2.3* / 43%

NATIONAL / 1.6 /

2.2 / 36%

* The most recent

year of available data is 2005.

NOTES: Time Served

estimates are in years. Ohio is omitted

due to irregularities with 2002 data.

SOURCE: Pew Center

on the States, 2012.

EXPECTED TIME SERVED

The length of stay

(LOS) measure used

in this report, the most common method

for calculating time served in prison, is

the average time served for all inmates

who were released in a particular year.

However, this is only one means of

measuring LOS in prison and, when there

is wide variation in sentence length or

when offenders are serving a very long

time, this method may underrepresent

certain types of offenders in any given

release cohort. For instance offenders

sentenced to 25 years to life in prison

are not counted in the average until they

are released, perhaps 30 or 40 years after

entering prison.

The purest method of

measuring LOS

would involve tracking inmates over

the full duration of their sentence. For

instance, we could track every individual

who enters prison in a given year from

admission through release and count the

total amount of time served. This would

provide an accurate picture of how long

everyone stayed in prison; however, the

time horizon it would require to track

every admission through their eventual

release makes this approach prohibitive.

Thus, statistical means are required to

estimate LOS based on actual releases,

attempting to account for offenders who

have yet to be released.

One such approach

involves estimating

the expected LOS of individuals who are

in prison during a particular year. This

measure accounts for offenders serving

longer sentences who are less likely to be

released in a given year, such as serious,

violent criminals. This is estimated using

both the stock population (how many

offenders are in prison at the end of the

year) and the number of offenders released

from prison during the same year. (See

Appendix A for details on methodology.)

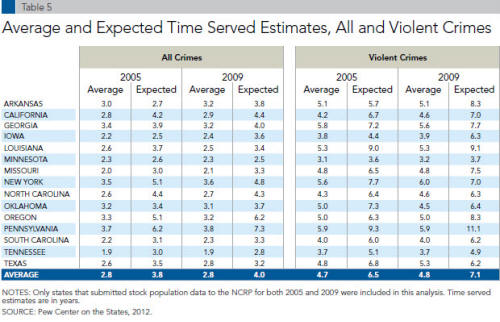

The expected LOS

measure found that

violent offenders entering or remaining

in prison in 2009 could expect to spend

about 7.1 years in custody, more than

two years longer than the average LOS for

violent criminals released in that year (see

Table 5). This difference is more significant

in states in which a larger portion of the

prison population is made up of long-term

inmates. For instance, in Louisiana and

Pennsylvania the expected LOS for violent

criminals in prison in 2009 is 9.1 and 11.1

years respectively, significantly longer than

the 5.3 and 5.9 years served by offenders

in the 2009 release cohorts for those states.

Looking at murder, Pew

finds an even

starker difference. The expected time

served for murder in 2009 is 38 years,

almost triple the 14 years served on

average by murderers released in that year.

In California and Georgia, states with large

populations serving life terms, expected time

served for murderers is more than 50 years,

compared with averages of 16 and 20 years

in their release cohorts.

For property and drug

offenders, who are

already cycling through the system relatively

quickly, the expected time served calculation

makes less difference. In some states, with

a few long-serving drug and property

offenders and a large population serving

short stays, the expected time served for

offenders in these categories is lower than

the release cohort estimate.

There is no perfect

measure of LOS. The

release cohort measure inspires confidence

because it counts actual time served by

actual people. But research has shown that

the expected time served measure generally

gets closer to the average we would find

if we could track each individual into the

future.12 Unfortunately, states frequently do

not collect the data necessary to conduct

these analyses. States can improve their use

of data-driven policy making by making

sure they are collecting and publishing the

information necessary to calculate different

measures of LOS, thereby providing a better

understanding of the sentencing and release

policies in their jurisdictions.

Table 5. Average and

Expected Time Served Estimates, All and Violent Crimes

NOTES: Only states

that submitted stock population data to the NCRP for both

2005 and 2009 were included in this analysis. Time served

estimates are in years.

SOURCE: Pew Center on

the States, 2012.

Unpacking the Numbers: What Shapes Length of Stay?

Length of stay (LOS)

is driven by a

complicated interaction of crime and

conviction rates and policies and practices

within each of the three branches of

government. These include criminal penalty

statutes and the relative funding provided for

prisons and alternatives by the legislature;

sentencing policies and decisions by the

courts; and release policies set by parole

boards and corrections departments within

the executive branch. States differ in terms

of which factors are the most significant

predictors of time served and how those

factors interact. For these reasons, assessing

the policies and practices that impact time

served requires an examination of all stages

of criminal case processing.

Crime and Conviction

Rates

Drive Mix of Prisoners

At the most basic

level, the average time

served by the overall state prison population

is driven by who goes to prison. If a prison

population is largely comprised of serious

violent offenders, average time served

will be longer than if the population is

heavily weighted toward drug and property

offenders. Rising rates of violent crime,

accompanied by rising arrest and conviction

rates, will therefore lead to longer overall

time served, assuming everything else

remains the same. But a state’s offender mix

also can be affected by deliberate policing

decisions, such as a sustained crackdown

on drug and quality of life crimes. If drug

offenders are arrested as a result of strategic

policing crackdowns, and then convicted

and sentenced to prison at a higher rate, the

overall average time served might decline,

even with no change in the underlying

violent and property crime rate.

Legislators Take the

Lead on

Sentencing Policy

In most states,

legislatures are responsible for

creating and approving changes in sentencing

policy. Statutes establish the baseline for all

criminal sentences, including the minimum

and maximum terms, requirements for the

percentage of sentence that must be served,

and whether offenders can earn credits

toward sentence reduction.

Beyond this baseline,

states’ approaches to

shaping sentencing vary considerably. In

Texas and Georgia, judges in most cases

have the authority to sentence anywhere

within broad statutory ranges, which can

stretch from probation all the way to 20

years in prison and beyond. Some states,

such as Maryland, have voluntary guidelines

that recommend sentences within wide

ranges inside the statutory boundaries, and

judges can depart from the guidelines without

stating reasons. A few states, typified by

North Carolina, have stricter guidelines that

prescribe sentences within narrow bands

unless the court finds and articulates special

circumstances. Since the late 1980s, states have

used sentencing policy changes both to drive

up (California and Pennsylvania) and to restrict

(Wisconsin, Oregon, and Minnesota) average

time served.13

The U.S. Congress also

has played a role at the

state level, by creating incentives for certain

types of sentencing policies. Specifically, the

Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement

Act of 1994 provided federal Violent-Offender

Incarceration and Truth-in-Sentencing (VOI/

TIS) grants to states that require violent

offenders serve 85 percent of their sentences.

While there is evidence suggesting that states

would have enacted such policies without

federal intervention, these grants helped

accelerate prison expansion.14 Missouri is

a good example of a state that overcame

concerns about overcrowded prisons with

the encouragement of the federal legislation,

expanding capacity by 30 percent with the

help of the grants.15

Courts, Prosecutors

Decide

Fate of Individual Cases

Decisions about how to

charge a defendant after

arrest and booking can have a profound impact

on future LOS in prison. In most instances,

prosecutors have significant discretion in

determining which charges to file. Defendants

are frequently booked for a host of crimes

and prosecutors prioritize offenses, a choice

influenced by factors such as severity of the

offense and quality of the evidence. While

some charging decisions are fairly cut-anddried,

others involve a process of deliberation

within the prosecutor’s office. The outcome of

that deliberation—whether a drug offender is

charged with trafficking, sales, or possession

with intent to distribute, for instance—can

have a substantial impact on plea negotiations,

sentence length and, ultimately, on time

served. Moreover, many states have habitual

offender laws with sentence enhancements

that can greatly boost time served in prison.

For example, in California, prosecutors can

choose whether or not to charge certain offenses

as a “strike,” making an offender eligible for

prosecution under the “three strikes” law. (For

more information, see the section on California.)

After the decision

about what offenses to charge,

prosecutors also have discretion to offer a plea

package to the defendant. National estimates

suggest that 94 percent of all criminal charges

are disposed of through pleas.16 Prosecutors

have flexibility in negotiating these agreements,

and, depending on court rules, may agree

upon a sentence in the plea process without

involving a judge at all. With nearly every felony

case being disposed of by plea negotiation, the

impact on sentence length and time served

cannot be overstated.

While judicial

discretion has been curtailed

in many states during the past few decades,

judges ultimately determine the disposition

and duration of the vast majority of sentences.

In half of the states,17 most felony criminal

sentences are indeterminate, and judges retain

significant discretion to hand down penalties

that are defined by broad statutory ranges.18

While the parole board retains ultimate

release authority in an indeterminate system,

eligibility dates for release are determined

by the judge’s initial sentence. In states with

sentencing guidelines, courts sentence within

smaller prescribed ranges of varying sizes,

but can depart from those ranges when

the case presents aggravating or mitigating

circumstances. This can result in significant

variation in sentence length and time served.

Regardless of the specific sentencing system

in each state, sentences typically vary, often

widely, from district to district and from

courtroom to courtroom.

Parole Boards Make

Release

Decisions

In terms of back-end

policies that influence

LOS, the use of parole—whether it is available

and, if so, how it is granted—is a major

contributor to the variations in time served

among states. In many states, release from

prison is discretionary, governed by a parole

board that develops criteria to assess an

inmate’s readiness for release and sets a date.

The parole board exerts significant influence

on time served. Factors such as offense type,

criminal history, program completion, conduct

while in custody, and risk of re-offending are

considered by parole boards when deciding

whether to release an offender. In reviewing

such factors, board members typically possess

a substantial degree of discretion to determine

the ultimate parole date.

In many states,

year-to-year changes in parole

policy, board membership, the board’s release

criteria, and type of inmates who come up for

parole review can have a profound effect on

grant rates, thereby driving time served up

or down. In Texas, recent changes to parole

guidelines that have redefined risk categories are

thought to have resulted in an increase in parole

grant rates. In September 2010, the parole grant

rate was 29 percent. By February 2012, that

figure had increased to 42 percent, resulting in

800 more offenders being released to parole in

that month compared with September 2010.19

In some cases, parole boards decide not to

consider release until a certain percentage of the

sentence has been served.

Board members’

discretion is not the only

dynamic that can influence the release date.

If board members value programs that

prepare inmates to return to life outside the

walls, such as substance abuse treatment or

literacy, they may postpone release until those

programs can be completed. A recent survey

of parole releasing authorities found that lack

of inmate programming was the single biggest

factor in delaying release.20 Other common

obstacles to release include an offender’s

inability to attend a review hearing; the lack

of timely post-sentence and other investigative

reports; and the absence of victim input.

Even basic

administrative troubles related

to parole boards can affect length of stay.

Pennsylvania typifies this experience; at one

point in late 2011 its board was short two

members, leading to 800 fewer parole cases

processed each month and a backlog of

prisoners awaiting parole consideration.21

Putting the Pieces

Together: Examples from Three States

To help understand how

the various factors influencing time served interact, it is

helpful to

look at the experience of individual states. Florida,

California, and Pennsylvania all had

large changes in length of stay (LOS) from 1990 to 2009. In

each state, multiple policies and

practices shaped the numbers in different ways and at

different moments during the study

period. Their stories illustrate the importance of looking

beyond the overall figures.

Florida

Factors Driving LOS

Changes

• 1995

truth-in-sentencing/85 percent rule

• Tougher penalties,

including 10-20-Life

• Increasing

incarceration of drug offenders

and use of “Year and a Day” sentences

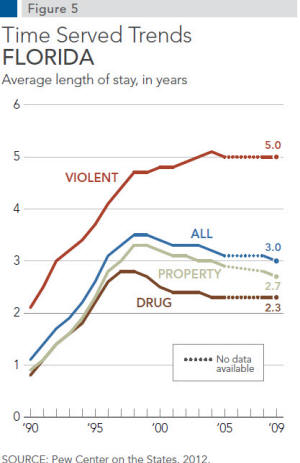

Florida stands out

among the states for

the dramatic increase—166 percent—in

time served during Pew’s tracking period

and for the twists and turns in policy

that influenced the numbers over time.

In 1990, the average LOS by a Florida

prisoner was just 1.1 years, the shortest

among states (see Figure 5). It was easy to

see why. Throughout the prior decade, a

capacity crunch combined with court limits

on prison overcrowding drove Florida to

adopt generous policies on “gaintime” that

reduced offenders’ time in prison. These

included some credits that were automatic,

rather than awarded based on program

participation or good behavior. “We called

it ‘walking around breathing time,’ because

the moment an offender entered the system,

he got 30 percent off his sentence,” recalled

Amanda Cannon, staff director of the state’s

Senate Criminal Justice Committee. As a

result, inmates in that era served only about

30 percent of their court-ordered terms.

By the mid-1990s, the

national truth-in-sentencing

movement was at full throttle,

and Florida—where outrage lingered

over the murder’s of two Miami police

officers by an ex-offender released after

serving only half his term—was ready for

a pendulum swing. Prison capacity had

increased, the 1993 killing of a British

vacationer had stained the state’s image as

a tourist playground, and a group called

Stop Turning Out Prisoners (STOP) was

attracting a large following. STOP’s push

for a state constitutional amendment

requiring offenders to serve 85 percent of

their sentence was blocked by the Florida

Supreme Court. But in early 1995, the state

legislature voted unanimously to enact the

85 percent rule for all offenders, regardless

of the crime.

Accompanying that step

was a steady stream

of bills that toughened penalties for specific

felonies. These included longer sentences

for sex offenders and murderers, mandatory

minimum terms for home burglary,

aggravated battery, and other crimes, as

well as new penalties for violent habitual

offenders. Perhaps the highlight of Florida’s

escalating toughness was its 10-20-Life

law, passed in 1999. The law imposed new

penalties for possessing, pulling, or firing

a gun during commission of a crime, and

mandated terms of 25 years to life in prison

for those who injured or killed someone

with a firearm. Offenders sentenced under

the law may not earn time credits to reduce

their terms.

In addition to

authorizing stiffer sentences,

the Legislature in 1997 adopted the

Criminal Punishment Code, which

created greater discretion for judges in

sentencing, increased penalties for many

crimes, and made more felony offenders

subject to mandatory prison terms. The

revisions, along with the proliferation of

longer sentences overall, gradually gave

prosecutors greater leverage to negotiate

plea bargains, which now make up about

98 percent of case dispositions in Florida.

As effects of the new penalties and time-served

requirements percolated through

the system, the

average time served by

offenders ticked upward. In 1995, the year

the 85 percent rule passed, the average

LOS for violent felons stood at 3.7 years,

but by 2005, it had reached 5.0 years.

Counteracting that trend, however, was

an influx of offenders with comparatively

short terms, whose arrival in the system

helped push the overall LOS number down

beginning in 1999. In fiscal year (FY) 1996-

97, for example, drug offenders made up

22.6 percent of new admissions, but by FY

2006-07 the proportion was 30.6 percent.22

Moreover, between 2003 and 2008, Florida

experienced a big jump in the use of “year

and a day” sentences. This is notable

because offenders sentenced to a year or

less serve their time in local jails rather

than in state prisons. These “year-anda-

day” sentences often were imposed by

courts under pressure to relieve crowding

and costs in their local jails and included

a large proportion of offenders snared by a

Department of Corrections policy requiring

“zero tolerance” for probation violations.

The policy was revoked by 2008; but, while

in effect, the number of violators sentenced

to prison rose by nearly 12,000.

Figure 5. time Served

Trends

FLORIDA

SOURCE: Pew Center on

the States, 2012.

Putting the Pieces Together: Examples from Three States

To help understand how

the various factors influencing time served interact, it is

helpful to

look at the experience of individual states. Florida,

California, and Pennsylvania all had

large changes in length of stay (LOS) from 1990 to 2009. In

each state, multiple policies and

practices shaped the numbers in different ways and at

different moments during the study

period. Their stories illustrate the importance of looking

beyond the overall figures.

Florida

Factors Driving LOS

Changes

• 1995

truth-in-sentencing/85 percent rule

• Tougher penalties,

including 10-20-Life

• Increasing

incarceration of drug offenders

and use of “Year and a Day” sentences

Florida stands out

among the states for

the dramatic increase—166 percent—in

time served during Pew’s tracking period

and for the twists and turns in policy

that influenced the numbers over time.

In 1990, the average LOS by a Florida

prisoner was just 1.1 years, the shortest

among states (see Figure 5). It was easy to

see why. Throughout the prior decade, a

capacity crunch combined with court limits

on prison overcrowding drove Florida to

adopt generous policies on “gaintime” that

reduced offenders’ time in prison. These

included some credits that were automatic,

rather than awarded based on program

participation or good behavior. “We called

it ‘walking around breathing time,’ because

the moment an offender entered the system,

he got 30 percent off his sentence,” recalled

Amanda Cannon, staff director of the state’s

Senate Criminal Justice Committee. As a

result, inmates in that era served only about

30 percent of their court-ordered terms.

By the mid-1990s, the

national truth-in-sentencing

movement was at full throttle,

and Florida—where outrage lingered

over the murders of two Miami police

officers by an ex-offender released after

serving only half his term—was ready for

a pendulum swing. Prison capacity had

increased, the 1993 killing of a British

vacationer had stained the state’s image as

a tourist playground, and a group called

Stop Turning Out Prisoners (STOP) was

attracting a large following. STOP’s push

for a state constitutional amendment

requiring offenders to serve 85 percent of

their sentence was blocked by the Florida

Supreme Court. But in early 1995, the state

legislature voted unanimously to enact the

85 percent rule for all offenders, regardless

of the crime.

Accompanying that step

was a steady stream

of bills that toughened penalties for specific

felonies. These included longer sentences

for sex offenders and murderers, mandatory

minimum terms for home burglary,

aggravated battery, and other crimes, as

well as new penalties for violent habitual

2010 report by the California State Auditor

concluded that offenders sentenced

under the three strikes law would serve,

on average, nine years longer than they

otherwise would have for their crimes.

Meanwhile, California

has long struggled to

provide sufficient rehabilitation and work

programs in its prisons; participation in

such programs is one way eligible offenders

can earn a reduction in their time served.

One study found that for offenders released

in 2006, half had not attended a single

rehabilitation program or work assignment

while behind bars.24 Budget troubles create

one barrier, and overcrowding means

competition for slots and a lack of space in

prisons, where even the hallways have been

filled with beds. Violence, exacerbated by

the overcrowding, also has led to frequent

lockdowns, during which programs are

suspended.

With the largest state

correctional system

in the country, California is currently

in the throes of a major policy shift that

will substantially lengthen the average

time served by offenders in its prisons.

Beginning in October 2011, the state

began to divert thousands of incoming

non-violent offenders from prison to

county jails. This “realignment,” developed

by Gov. Edmund G. (Jerry) Brown Jr. and

approved by the legislature as Assembly

Bill 109, came in response to a U.S.

Supreme Court order on overcrowding

that requires the state to reduce its prison

population by about 35,000 inmates by

mid-2013. Because of the realignment,

offenders’ average stay in prison is roughly

12 months, mostly for drug and property

crimes. Their absence from the population

will create a heavier concentration of

inmates serving longer terms.25

“ I think if you

had a list of all

the potential factors that

could drive up LOS in prison,

California would have a check by

every one of them.”

—Joan Petersilia,

co-director, Stanford Criminal

Justice Center

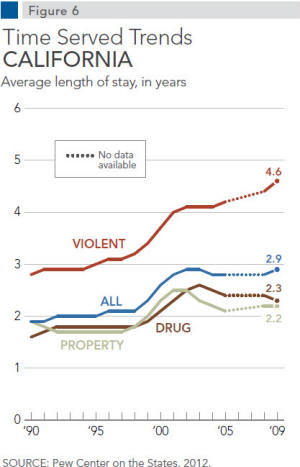

Figure 6. Time Served

Trends

CALIFORNIA

SOURCE: Pew Center on the States, 2012.

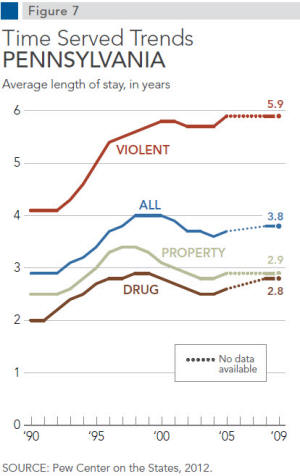

Pennsylvania

Factors Driving LOS

Changes

• Use of jails to hold

offenders with shorter sentences

• High-profile crimes

leading to changes in parole board practices

• Alternatives for

drug offenders

In Pennsylvania, the relatively long

average time served by offenders in state

prison reflects the Keystone State’s heavy

reliance on county jails. In 2010, jails

represented 33 percent of all criminal

sentences imposed in Pennsylvania, while

state prisons accounted for just 13 percent

and the balance went to probation or

other alternatives, proportions that have

held steady in recent decades.26 “Clearly,

that skews the offender mix in prison

toward people serving longer terms, so the

average length of time served is naturally

longer,” said Mark Bergstrom, executive

director of the Pennsylvania Commission

on Sentencing. In addition, offenders

serving life terms in Pennsylvania—about

4,300 people, or 9.4 percent of the prison

population—are not eligible for parole,

and, until 2008, Pennsylvania inmates

were unable to accumulate earned time,

two factors that also increase time served.

Like California and Florida, Pennsylvania

adopted increasingly tough penalties

for felons through the 1990s, steadily

nudging the LOS average for violent

crimes higher. But in contrast to those

states, Pennsylvania operates under an

indeterminate sentencing structure,

so its experience also has been shaped

heavily by actions of its parole board.

In the 1980s, the governor-appointed

board tended to grant parole to most

offenders when they had served their

minimum term, barring misbehavior

behind bars. But periodically in the

past two decades, high-profile crimes

committed by parolees have caused spells

of increased caution on the part of the

board, triggering a drop in the parole rate

and thereby increasing the average time

served in prison.

One notable episode

came in 1995,

when a paroled offender named Robert

“Mudman” Simon shot and killed a

police officer just three months after his

release. During the previous year, 72

percent of prisoners who were eligible

and applied for parole received it, and