|

|

|

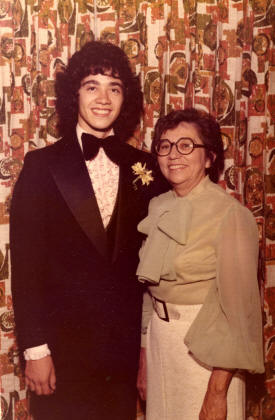

Ancestors

by Charles Carreon

7/14/13

“The bad thing about when people die is it leaves everybody else

fucked up. They’re gone and it’s no more problem to

them. it’s just sad for everybody that’s left.” — Sonny

Barger

Eloise

It is a quiet afternoon, on a summer afternoon in Arizona,

starting to shade towards dark. There is a helicopter in the

middle of the street outside my parents’ house. My mother is

lying dead in the backyard, the victim of a tragic drowning

accident. My two older children, whom she was supposed to be

watching, instead saw her drown, unaware that she had

suffered a stroke, and was not deliberately doing a dead-man

float.

My wife screaming my name told me that horror had descended

upon us. I vaulted over the eight-foot fence in one

movement, and was in the backyard. There she lay, a mere 67

years old, not breathing on the concrete where Tara had

dragged her. Tara ran inside to call 911. I began artificial

resuscitation. It was the first time I ever touched my mom’s

lips with my own. We were very Mexican-Catholic that way.

When the paramedics cut away her swimsuit, it was the first

time I remember ever seeing her breasts, though she

breastfed me. Everything, everything, everything about this

scene was so horribly wrong. I had been a mere forty feet

away, working on my truck, readying it for the drive back to

Oregon. My mom had wanted to drive back with us. I told her

to fly up in a few weeks, so we wouldn’t be cramped like we

had on the drive down with her a month earlier.

She had been clinging to the life and love of our family.

The day before, mom had expressed how terribly she would be

missing Ana, our youngest child, still a nursing infant,

radiant as a china doll with gleaming ebony eyes. My mom,

whose name was Eloise, was carrying Ana around on her hip,

doting on her, and what came out of her mouth was, “Oh, you

are so beautiful. I am going to miss you so much. Tomorrow I

will be walking around here like a dead man.”

Mama had become a prophet, and it was no surprise she had

intuited her coming death. She was quite nearly a saint, not

by virtue of attending Mass, although she loved to sing in

the choir, but by virtue of her well-known kindness and

generosity. When she met my Buddhist lama, she happily took

the vows of refuge, joining our Buddhist family without

hesitation. The lama, a mischievous man with a puckish sense

of humor, responded to my suggestion that we get her some

Dharma books to read with a dismissive wave, remarking with

good-humored disdain and a wrinkled brow, “Books? What does

she need with books?” I went on with a flowery statement

intended to flatter myself by association — “Rinpoche,” I

said, “if I have any seed of compassion, you see where I got

it.” The statement was silly, since all beings have the seed

of compassion which is the seed of enlightenment, and

Rinpoche’s response was a pomposity-deflating riposte that

still makes me smile. “Well,” he replied, alluding to my

seed of enlightenment, “before, I did not know you had one,

but now I see that you do, so you must develop it.” I never

forgot how deferential Rinpoche, who rarely suffered fools

of any age, had been towards Mom. He really acknowledged

that her self-evident goodness required no improvement. I

have felt her presence beside me at major decision points in

my life again and again, guiding me to do only those things

that she would be okay with, and it has never steered me

wrong.

Mom’s funeral was held a week after she drowned, because we

kept her on a ventilator and watched her flat brain waves

for seven days until my dad said to unplug the damn

ventilator, because otherwise she was going to die of organ

failure and basically rot in front of us. Well over a

hundred people showed up to the funeral. I didn’t know at

least half of them. Many, many people introduced themselves

and told me how much she had meant to them, of how kind she

had been, of how fortunate we had all been to know her. None

more fortunate than my brother, my father, and I. And none

more bereft, now.

Guilt choked us all. My brother and Dad had been campaigning

for a friend up in Prescott that day, helping a friend of my

brother’s who was running for Arizona Attorney General.

Suddenly, their big-wheel political act seemed like a

terrible, misplaced priority.

My father was furious with me. He barely spoke. His grief

was like a huge, black iron that crushed everything. My

father’s whole life turned to hell, because I, the only man

in charge of the house, had been doing some stupid,

mechanical bullshit, instead of watching my mom. He never

said this, but I knew he thought it. He wasn’t into

consolation. He’d spent the last eighteen years earning a

federal pension, the two of them had just retired and bought

a new house with a pool because, irony of ironies, after

conquering a lifetime fear of water and drowning, she had

become a daily swimmer. After a week of enduring my father’s

silent ire in the house inhabited by my mother’s spirit,

whose voice I could hear resounding in every room and

hallway, we packed up and split for Oregon.

The drive home was a nightmare. We were broke, and our two

new front tires were worn bald by the time we got to Lodi,

California, because the idiot shyster tire guys in Phoenix

had grossly misaligned the front wheels when they put them

on. My mother-in-law helped us out with her credit card and

a real decent guy in Lodi named Charles Gomes got us back on

the road with a new pair of tires.

When we got back to our yurt on the Buddhist retreat land in

Southern Oregon, I was saved from desperate grief by a

miracle. Perhaps those who have never known the love of a

truly kind mother cannot understand my grief. It was as if

the sun had gone out. There was no sense to life at all. My

son Joshua was devastated with guilt, being nine, and old

enough to realize after the fact, that grandma had needed

help, and he could have gone and gotten Mom, but he sent

Maria, and Maria didn’t understand at all that there was a

problem, and neither did Josh, really. But everyone felt

terrible, and Josh developed crying jags that would continue

for an hour or more, when the grief and tears would flow

uncontrollably. For truly, she had been like the sun for all

of us, a source of love so dependable and true that it made

the world bearable, and now she was gone, irretrievably

gone. Things would happen, good or bad, and I’d want to call

her, but I couldn’t, ’cause I didn’t have that number.

But we did get a miracle, and our lives were saved from

utter destruction. The day we got back to Colestine Valley

in Oregon, we saw that Rinpoche had begun a Great Work, the

construction of a 22-foot high concrete-and-steel Buddha

statue, to be built on a ten-foot concrete foundation.

Rinpoche took me aside as we stood together, working on

building the concrete forms for the foundation that we were

constructing entirely without permits, zoning, or building

code approvals. We were outlaw Buddhists, in every way. And

as I stood next to my lama, he told me, “Don’t do anything

but work on this statue. Don’t work for money or look for a

job. Just do this, and dedicate the merit to the benefit of

all living beings, with your mother as their

representative.” He turned to scan the work site, where

about twenty hard-core hippies, ex-dope-dealers,

scene-seasoned women, and deadheads were gaily doing the

ultimate in New-Age construction work, working like beasts

for free. Then he looked back at me and said, “These people

don’t know what this is all about. You do.” He meant I knew

that death is why we practice Buddhism.

I got the message and obeyed Rinpoche’s command, for his

words were commands to me. I always obeyed him. When he told

me to stop fighting with Tara, I did. When he told me not to

fall in love with other women, I stopped doing it. We had no

money for three months, and lived solely on food stamps and

on tiny donations from the dozens of people Tara was

feeding. Rinpoche drove everyone mercilessly. The entire

statue was built with hundreds of yards of concrete mixed

and poured in small batches onsite, because no concrete

mixer truck would cross the bridges between the statue site

and Colestine Road. We ran wheelbarrows of wet cement up a

twenty-five foot ramp at a 30-degree angle, using two-guy

teams. We drank an endless supply of beer, ten or twelve

cans a day, and barely felt it, we were working so hard.

People fell in love that summer, some people ended up

getting divorced. People came into the Sangha who have never

left. We had genius-level people mixing concrete. We had

abundant profanity and crude jokes. Much like the Blues

Brothers, we were free to do anything to advance the

project. We were on a mission from God. It was a hell of a

scene.

During that summer, Rinpoche also wanted to teach us Dream

Yoga, so we could practice meditation during our sleep, a

time during which, as Rinpoche noted, we couldn’t claim to

be otherwise occupied with things like work or school. As

part of the dream yoga teaching, Rinpoche taught us how to

deconstruct the solid world of appearances, that he said was

just a curiously-solid dream.

Rinpoche also taught us about how to disassociate names from

their objects of reference. He taught us that “cup” is a

word, and what it refers to is a piece of ceramic molded

into a liquid-holding device that will someday break and not

even be a cup anymore, but will become something called

“trash.”

Most importantly, Rinpoche taught us that our names were

distinct from ourselves. To help us play with this concept,

for one week we were assigned a practice called

“transcending praise and blame.” He told us that for one

week, we should practice saying nasty, abusive things to

each other. Being a gang of untamed post-hippie, proto-yogis

with rock and roll craziness as our foundation, we took to

faux-hostility like pigs to mud.

So on any given day, for at least a week, walking around the

job site, people would come up and abuse you. Driving down

Colestine Road, old Mitchell Frangadakis, the ex-grade

school teacher, would pull over with Pat Hansen, the

ex-Marine semi-hooligan, and we’d lay into each other with

streams of invective, smiles showing all around. Then we’d

drive off abruptly, apparently in a rage. It was hilarious,

but I don’t think we made much progress in dropping our

self-regard. Maybe for Tibetans, the faux-abuse would have

meant something, but hippies were used to behaving crazily,

so it was basically just a hoot. Years later, I think we’re

all still attached to our names. In all candor, I had no

real idea what the practice was all about until June, 2012.

The summer wound to a close, and I had to go back for my

senior year at Southern Oregon State College. I was trying

to decide what to do for graduate school after I got my B.A.

in English. I knew I didn’t want to be powerless and

resigned, like all my friends who were English professors.

Shortly after Mom drowned, when she was in the hospital on

the ventilator, I was watching a Sunday morning political

show with the usual suits talking politics. I thought, “I

could do that.” Later, in the grocery store, I asked Tara if

she thought I should be a lawyer. She said definitely, yes.

Three months later, I was standing with Rinpoche at the

statue site. We were spreading concrete, I believe, and I

said to Rinpoche, “I’m thinking of going to law school.”

He said, “Do it.”

I said, “It’s kind of weird karma.”

He said, “I think it’s great karma.”

So the matter was settled.

My grief became manageable as the joy of working on the

statue of Vajrasattva, as the androgynous-faced Tibetan

Buddha, draped in jewels and silks, became a huge reality —

changing figure before our eyes, and the knowledge that I

was doing an act that could help my mother and all living

beings soothed my pain. I became very, very poor, so poor I

had no money for shoes. I had to go barefoot, like an

Appalachian child, and I had children of my own. It was

humiliating, and the first thing I bought when I got my

student loan money was a pair of Chinese plastic track shoes

so cheap the soles weren’t even made of real foam, and

clicked when I walked on the hard floors of the English

department. But I made it back to the English department,

and I got my degree, and I took the LSAT, and I got into

UCLA, and I passed the bar, and I got a job at the world’s

fourth largest firm.

After I had been working a couple of years, my Dad came to

visit, and we were walking to a Mexican restaurant for

lunch, and as we stood on a street corner waiting for the

light to change, Dad looked up and around, taking stock. We

were both dressed in grey suits, because dad always wore a

suit if he was in a business environment, and of course I

wore a suit to my first job.

He looked up at the skyscrapers and then he looked at me and

said, “Son, you’ve done it, you’ve really done it. If only

your mother could be here now to see you.” He paused and

continued. “She told me, not long before she died, ‘You

know, Jimmy, I think that Charles is really going to do

something.’” With that, I knew Dad had forgiven me for Mom’s

death, and he also put a burden on me. Because aside from

getting a steady salary and paying student loans, I didn’t

think I’d accomplished enough to call it “really doing

something.” Mom had talked to my Dad, after all, who had

high standards for such things. Mothers love us regardless

of what we do. Fathers teach us to achieve goals. Between

the two, we can learn the lessons that make us decent

people. So we must ever protect their memory and their

names.

Jimmy

My dad’s name was Conrado Santiago Carreon, “Jimmy” to most

everyone. He had a ready smile, a courteous manner, and an

intrepid way of engaging any other human being in

conversation in virtually any situation. Dad had been

orphaned by the flu epidemic, twice, in fact, losing first

his natural parents, then his foster parents in Arizona. He

grew up in L.A., on his own from age 12 on. He became a

boxer fighting professionally during his teens, and nearly

died of tuberculosis before the age of 25, a victim of

drastic weight loss regimens he adopted to “make weight” and

fight in multiple weight classes. His first wife divorced

him and took his son while he was trying to survive TB. That

son, “little Jimmy,” as we knew him, met hard times early

with a mother who was not like my mom. Little Jimmy was in

and out of the military, out on the streets and into street

life, which in El Monte, California, gets pretty heavy

pretty quick. Jimmy eventually moved to Arizona with his

wife Honey and their four daughters, who were totally fun

cousins to barbecue and have a beer with, and for a while

there we had some good times. But, it didn’t last long.

Jimmy’s health caved in and he died in a rest home. A second

son, Andy, was killed at the age of four in a car accident.

When he married my mom, dad joined the large Ainsa extended

family, and things seemed to smooth out. His dynamism was

well-received by my mom’s family, especially during the

depression and war years. Dad had a way of raising money,

including running the occasional poker game. He truck farmed

and got deals from other produce guys. He got into politics,

and was elected to the Arizona State House of

Representatives six times.

Then he went to Washington, D.C., and worked for the

Department of Labor for 18 years. My mom stayed in Arizona,

working as a legal secretary for the State. I went to

military school in Virginia, and stayed with dad in D.C. on

holidays. He was a frugal man, who sent my mom most of his

salary, living very modestly in studio or one-bedroom

apartments, always overstuffed with books bought in the

city’s many remainder shops.

Eventually, he got moved back to Phoenix for a few years,

then he had to go to San Francisco due to office cutbacks.

So he and my mom spent a lot of time apart. He had an

unshakeable belief in the value of hard work, and worked

himself hard his whole life.

My mother’s death happened just after he had moved them into

a new house. Mom had retired from her job less than a year

before. They had prepared well financially for retirement,

so he was actually having a pretty good time. Mom was a

little at loose ends after being a legal secretary for many

years, but her health seemed fine, and she had quickly taken

advantage of her freedom to start spending time with her

three grandchildren — pure joy for her. To have it all end

in an instant was a terrible blow to dad. He and I had only

recently reclaimed our relationship after years of silence

due to his alienation from my failure to pursue a college

degree, early marriage, and disappearance to Oregon with my

wife and newborn child.

Mom’s death set us apart for many months, but when I told

him I’d gotten into UCLA Law School, he helped us to move to

L.A. and pay rent for many months. Dad was very fatalistic

about my chances of sticking with law school. I suppose

he’d never seen me stick with anything before, so why would

I stick with something as difficult as law school? He really

kept a lid on his scepticism though, because he never made a

single statement expressing doubts about my resolve. Years

later I realized that he had really thought that every

challenge I was facing would be the one to defeat me. He

kept expressing surprise at each additional success —

straight A’s in my second semester of first year, a summer

clerkship at the hot firm with the best salaries and

parties, and finally a top-paying job at a world-class firm

waiting as soon as I got my J.D. He never thought I had it

in me. So of course, our relationship just got better and

better as I became more and more of a professional.

I knew dad was lonely, and felt like I should move back to

Phoenix when I got my first job after graduation. I flew out

to interview and got several job offers. I stayed with him

in the house where he had devoted a room to a display of

mom’s clothes, hung all over the room. The room ached with

sadness. During my visit, he made it clear that he wasn’t

assuming I was moving back to Phoenix, and that I should

work in L.A. if that was best for my career. He also made it

clear that he would think better of me if I did not do

insurance defense work, that he described as “hard on the

soul.” Fortunately, it was easy to follow that advice,

thanks to getting top grades at a top school.

Dad kept an upbeat tone and a quick step as he aged. When we

all moved back to Oregon in 1993, he came and visited for

months, sleeping on my couch, while the life of a family

with three kids and a lot of visitors boiled around him.

Tara was working all week as a legal secretary at the

now-defunct Democratic liberal Heller Ehrman firm in Palo

Alto to earn some real money, while I studied for the Bar.

She commuted back to Ashland on weekends, but the Bar

happened during the week, so dad watched the kids while I

went up north to take the Oregon Bar exam. The kids took

advantage, and he got an eyeful. His stories about their

carryings-on with other second-generation hippies were quite

believable.

That was the last good time I spent with him, but over the

years he had spent many of my first lawyer experiences right

with me. He stayed in a Pasadena hotel with me when I took

the Bar in 1986. He flew to San Diego to hear my closing in

my first jury trial. I lost, and he was incredulous. My

argument had sold him!

He regained a measure of good cheer around our children,

clearly his favorite people in the universe. I liked being

with him. He was such a good man.

I think when it got dark, the sadness would get to him. At

night, all alone, he could only think of her, the one who

had departed, never to be seen again. He had always loved

Edgar Allan Poe — I even memorized much of The

Raven to

please him when I was around ten or eleven. Now he would

quote the poem’s lines, “seeking surcease from sorrow,

sorrow for the lost Lenore … gone, forevermore.” His head

would hang heavily then, and his arms go slack, his eyes

would sadden and the corners of his mouth would fall. His

loss was entire. Truly the world was of no use to him

anymore. He merely kept going from sheer endurance, thanks

to the stripped-down fitness regimen he maintained until

even after he started showing substantial signs of

Alzheimers in his late eighties. At that point, mercifully,

he appeared to forget his grief. Unfortunately, he also lost

all track of some people’s true identities. He did not

recognize me as “Charles,” when I sat before him and

reminded him, or rather, tried to remind him, of who I was.

He could recognize Tara, but when she pointed at me and

said, “This is Charles right here,” he would say, looking at

a photograph of me, “Charles is away, doing very important

work.” I was glad that he felt well about me, but I was

puzzled, frustrated that, in essence, I was unable to visit

with my Dad.

During the last two years of his life, I only came to see

Dad a half-dozen times, for short visits of a few hours. I

was a busy dad running my own business, with a lot of bills

to pay, but now I really regret having shown him so little

respect during those last two years. He didn’t “know me,”

but I could see he knew I was “somebody,” and that should

have been enough for me. I should have made more of an

effort to spend time being somebody with him.

I had an intimation I would fail in this way when I was

living in Santa Monica. We lived five blocks from the

Pacific Ocean in a beautiful house filled with light from

ample windows, surrounded by green lawns and big trees. You

could hear the ocean from that house during the quiet hours

of night and pre-dawn. Tara and I slept on futons close to

the floor. It was amazingly peaceful there, for L.A., and I

usually slept very well.

I woke up one night with my eyes drenched in tears, from a

dream that was breaking my heart. I saw my father, dressed

in outdoor clothes, standing in the middle of a sandy lot.

It seemed like it was a ranch out in the desert. He was all

alone, except for a little dog, a really sweet little dog,

that was keeping him company. I realized he was all alone,

and I woke up with the resolve to make more of an effort to

see him, but I didn’t follow up. I just kept on with the

once or twice a year thing, and the years went by.

My dad gave me everything he could — a love for education,

and a lifetime’s worth of great examples of what it means to

be a decent human being. He was generous and always

respected people who do physical work. He talked to cabbies,

waiters, and bohemians as if they were diplomats, as it

often seemed they were. I always remember asking my mom what

I should be when I grew up. A doctor? An architect? She just

frowned and shook her head lightly as if to say that it

wasn’t an issue of becoming any particular type of working

man. Then she said, “Just be a good man. Just be a good man

like your Papa. He’s a good man.” I only wish I had absorbed

all Dad’s lessons on being a good man earlier, and that I

were better at putting them into effect. All of his advice

was good, and my life would have been better if I’d started

following it sooner.

But I must say that the tragedy that my dad suffered, I have

insured against. He loved my mother deeply — they had

wonderful, exciting years together before I was born. My

father ran a string of businesses from agriculture to

industrial roofing contracting. With my mom and my brother,

he lived and worked in Mexico City for a year. Then he owned

a hotel in Puerto Punta Peñasco Sonora for another year.

Then he did the legislative job for no money, or rather,

$1,100 per year, which is about the same thing. When he hit

his fifties, he felt he had to buckle down and pull in that

retirement money. So he missed a lot of years he could have

spent with Mom. For Dad, the years of sacrifice were the

right thing to do. Or so he thought. But it really came to

naught, because having a retirement fund without Mom to

spend it with was just ashes in his mouth. Which is why I’ve

worked for myself for the last eighteen years. Most of the

time my beloved is in her office, and I’m in my office at

the other end of the house, a pendulum swing away from my

Dad’s way of doing things. But in our hearts, I know we

have the same approach to life. A sense of gratitude for

talent and opportunity, the guts to do something different,

an unbending will when dealing with bullies, loyalty to

those who have reason to depend upon you, kindness toward

those who cannot harm you, and vigilance towards those who

can – that would be my father’s creed, and mine, in a

nutshell.

I honor my Dad with my life, trying to show the same

courage, calmness, and kindly strength that he showed me

again and again over many years. I never stop mourning the

unique, terrible loss he suffered. One night, not long after

I had a dream about my mother, I wrote a poem to describe

his sadness.

Is It Thunder?

Somewhere between the gold and the black

I lost you –

You fell from my hand

Like a card from the deck,

And you’re gone–

I can’t retrieve

the things that we had,

I can’t reclaim

the hours that have slipped away.

There is nothing left but an empty horizon and you.

Like the sun coming out from behind a cloud,

A dream that couldn’t be true,

You were a vision in sunlight and lace.

Never was there another face

Like the one

That you wore.

But now that you’re gone I sit alone and I wonder,

Is it the sound of the rain that I hear?

Is it thunder?

Come back again in my dreams if you can,

You’re welcome if ever you choose

To join me there,

I don’t have much company these days,

I stay in the same old place

And I sit alone and wonder –

Is it the sound of the rain that I hear?

Is it thunder?

(Dedicated to my mother, Eloise Carreon and the Choir of

the Sacred Heart)

I never gave Dad the poem, or let him see it, because I can

barely stand to read it myself. It hurts so much to read it,

that I doubt I’ve read it more than a half-dozen times in

the thirty years since I wrote it.

The dream that prompted me to write this poem came to me

about a year or two after my mother died. In the dream, I

was visiting her in a nice room where the sun was shining in

through the window, and there were big green trees outside.

Mom told me, “I’m in a choir. It’s called the Choir of the

Sacred Heart.” She said, “I can’t see, but I can help

people.” She sounded very happy, and I thought to myself,

“Oh, this is wonderful. I am here with my mother, and I am

fully aware of her presence.” The light got brighter and

brighter, and I understood that, like me, she couldn’t see

because of the light, but we were together there in the

light. Then I woke up. I didn’t feel like I’d wakened from a

dream, but rather from a reality.

With that dream, I felt assured about my mother’s current

state. It put my heart at rest. She had more than once said

that drowning seemed like the worst way to die. Perhaps

because of this, I had suffered from the very painful,

repeated, vivid imagining of how she might have suffered as

she died, terrified and unable to help herself, with me

unaware of her plight. After the dream, reliving the event

that way came to an end.

My father apparently had no such reassuring experience, and

became bitterly resigned during the last few years of his

lucidity. He would go to church, go to Mass, but at heart he

seemed to express his final judgment of the situation when

he and I spoke one night outside an ice-cream shop in

Phoenix. He had separated himself from my brother and his

family, and Tara and our kids. He was standing, looking up

at the sky out over the big parking lot, as if he might find

some trace of Mom out there, in the absolute emptiness she

had left behind. I came up and said something consoling

about Mom. He said bitterly, not taking his eyes off the

stars, “I will never see her again.” This seemed so likely

to be the truth, that I didn’t argue with him about it then.

I have no better arguments now. Somehow, however, I think

that the peace and happiness he enjoyed with Mom during

their good times together was not the end of all his

happiness. Somehow I suspect that the essence of happiness

is as indestructible as it is ungraspable. Like gold melted

down and cast again into new coins, I believe that my

father’s bright and resilient spirit will take form again.

And if not, then it’s all the more important that his

lessons live on in the way I live my life. |